Design, creativity and oblique strategies!

Every creative field has its moments of particular tension, of doubt even, when an artist is faced with a creative block.

What’s the right thing to do? How do you bounce back to avoid repeating yourself? How do you get out of an impasse you feel is inevitable?

For years, many creative people have been examining this question. With a relatively similar starting point… “To create is to give life to something that didn’t exist before.” It’s a question of looking. It’s often a question of seeing beyond the ordinary and touching what was previously invisible, of going to the very depths of things. An important element in all this is chance, entrusting a decision or a choice to chance to get out of a rut.

In the late 60s, Edward de Bono developed the concept of “Lateral Thinking”, which involves looking at a problem from several angles rather than focusing on a tried-and-tested, but linear and limited approach. “Thinking outside the box”, ‘Hors du cadre’. His book “The Use of Lateral Thinking” was the first in a long line of best-selling works.

More recently, in “Créativité, un art de vivre”, Rick Rubin, a music producer, takes a more abstract, personal development approach to the question of creativity. Each chapter closes with a sentence that sounds like an aphorism. “Failure is the information you need to get where you’re going”, or ‘Going the wrong way at a fork in the road reveals landscapes you’d never have seen otherwise’.

Something reminiscent of a card game created half a century ago, but which is still so topical today that its creator, also a musician, remains so contemporary. Brian Eno’s “Oblique Strategies”.

Brian Eno and his oblique strategies

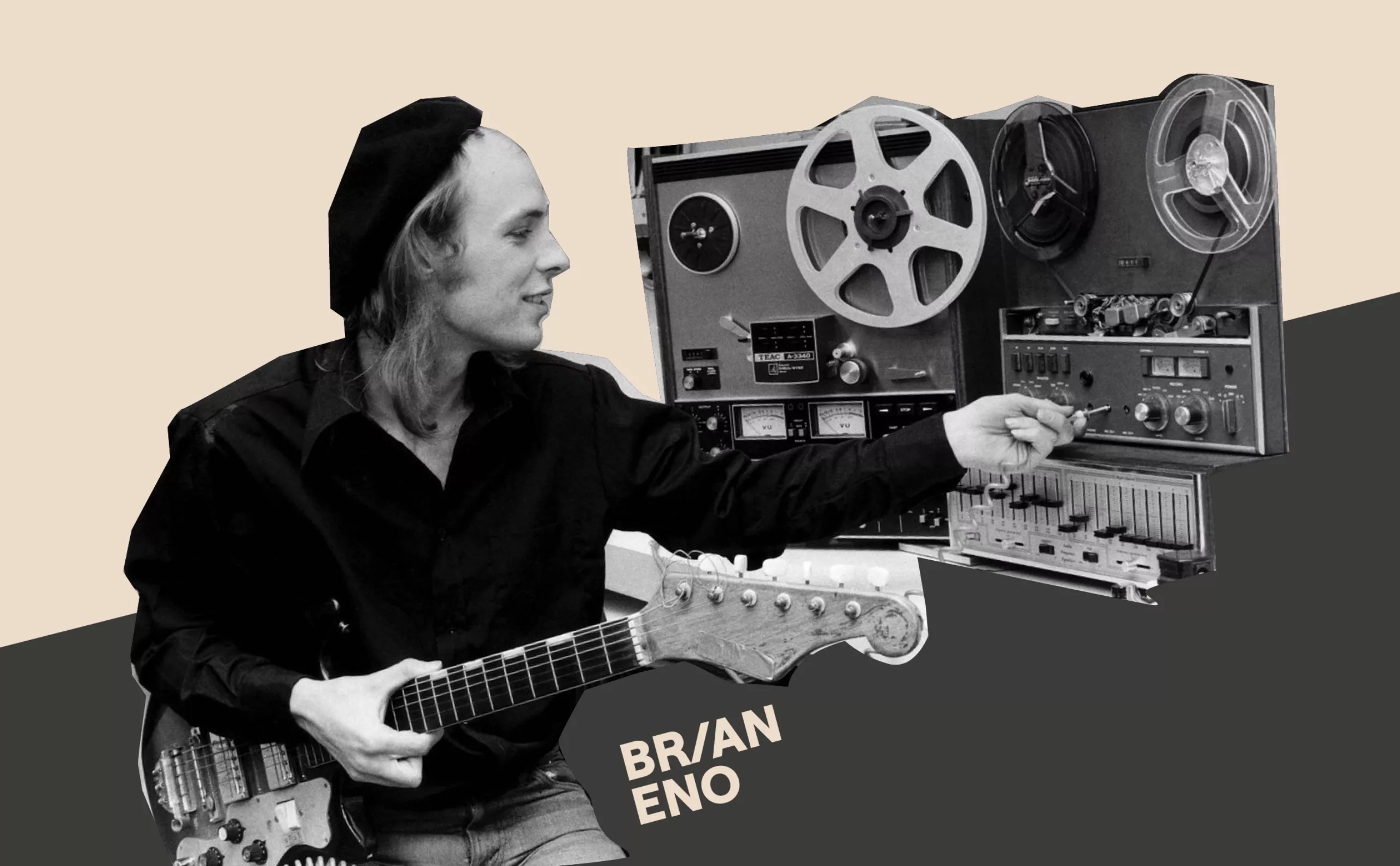

Brian Eno is a brilliant jack-of-all-trades. Today, we would describe him as a “transversal” creative artist (musician, arranger, producer, video artist, writer…) who has given a great deal of thought to the phenomena of creation. There’s something of a “trendsetter” about this avant-garde guru who crystallizes the energies of the present.

This enigmatic musician, pioneer of ambient music and producer for the likes of David Bowie, Iggy Pop, U2, Coldplay and Talking Heads, was quick to question the creative process.

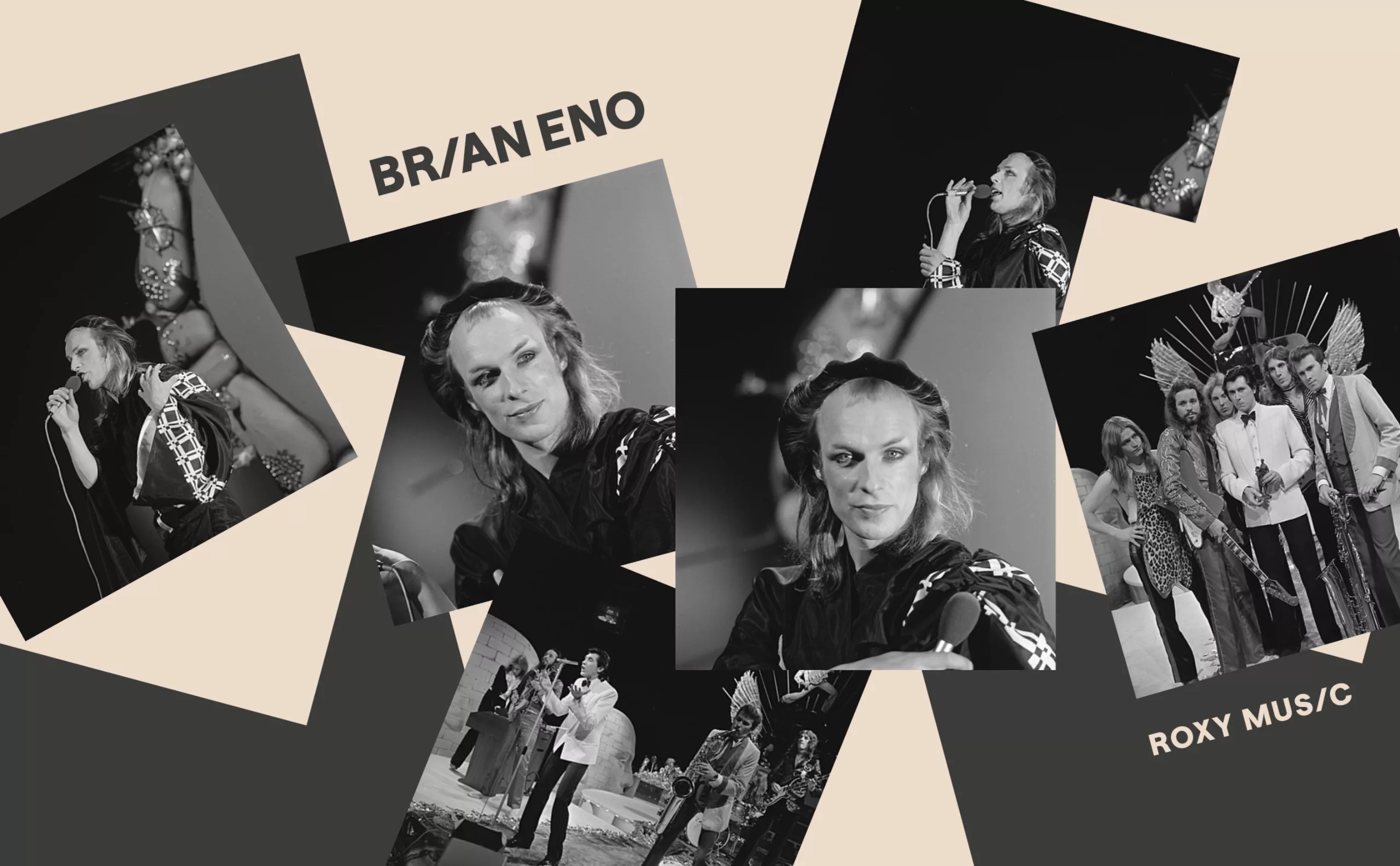

In 1972, Brian Eno joined Bryan Ferry’s group Roxy Music. At the time, their stripped-down record sleeves were as popular as their music. Amanda Lear’s appearance on “For your pleasure” made her a household name.

A magnetic, bewitching presence, Eno captures something of the rock band’s energy as a true pioneer of electronic sounds.

While remaining in the shadow of the leader, his androgynous silhouette takes on the light and Eno begins to express himself on a whole host of cultural subjects, more or less esoteric concepts, divinatory theories. He sees, he feels the times. A boundless seeker. There’s a musical “visionary” side to this “guide” who crystallizes the magnetism of the present for the benefit of his creation.

Concert after concert, he took up more and more of the band’s space. In 1973, the break with Bryan Ferry became inevitable, and he moved away from Roxy Music to work on atmospheric synthesizer sounds in the studio. That same year, he released a debut album of absolute mastery. “Here Come The Warm Jets

Brian Eno began methodically taking notes. During recording sessions, he wrote short sentences on pieces of cardboard. Thoughts, aphorisms. For him, the artist, like the oracle, is a vehicle, a transmitting element that brings things to the surface.

Is anything missing?

And as with all artists, there are moments of tension. What do you do when you’re in the studio and only have a few hours to finalize a track? How do you avoid doing the same thing over again? How to decadence the imagination…

Confronted with these creative impasses, he pulls out his notes and realizes that this may provide a spark for a new way of looking at things.

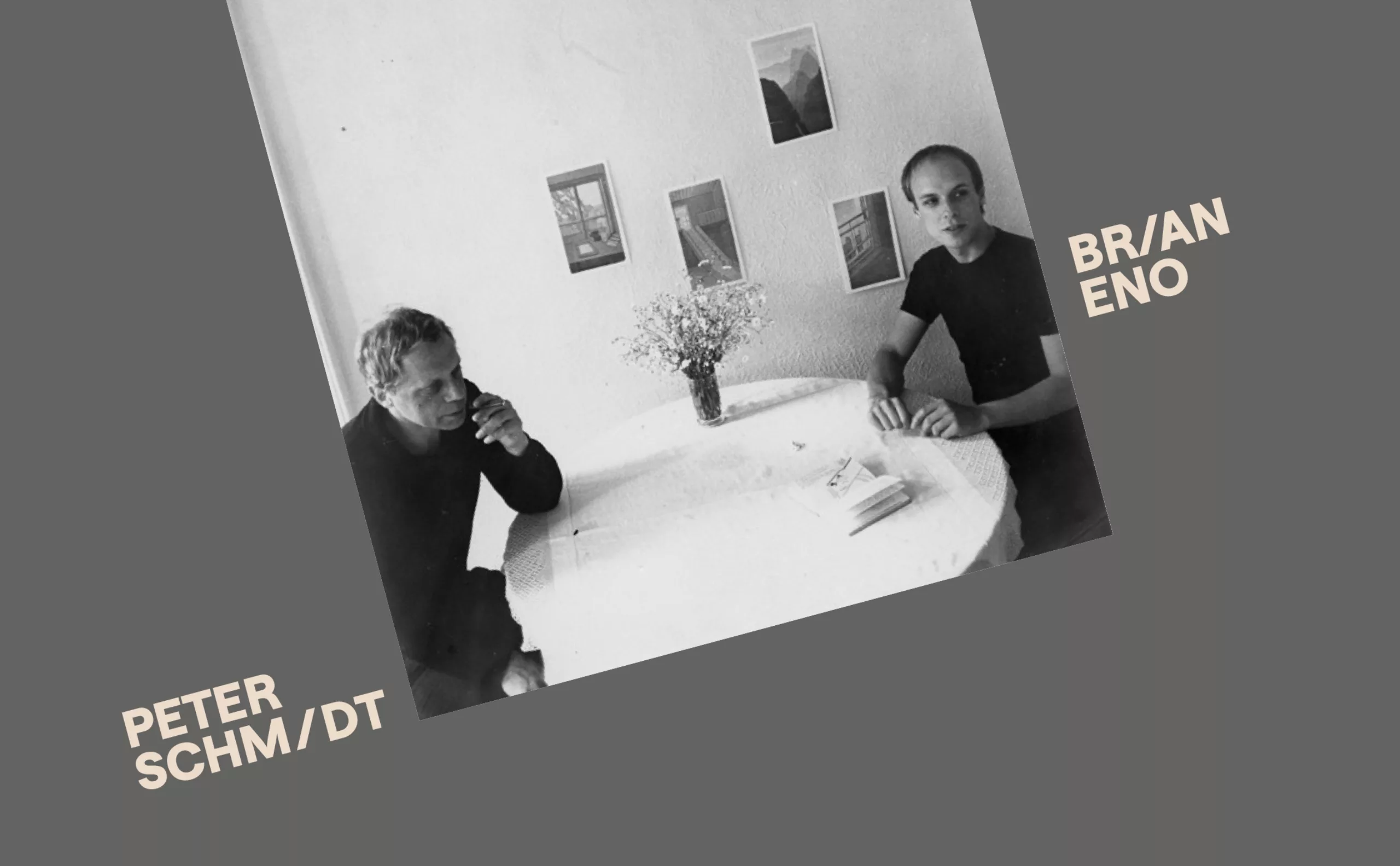

At the same time, he discovered that a friend of his, Berlin painter Peter Schmidt, was pondering the same questions about the creative process. A few years earlier, this artist had also produced a deck of cards containing 50 advice cards. Although they never talked about it, the two creators arrived at the same results, with almost identical cards.

On one of his first cards, Eno had written: “Recognize your mistakes as hidden intentions”, while Peter Schmidt’s read: “Was it really a mistake?”

Only a part, not the whole

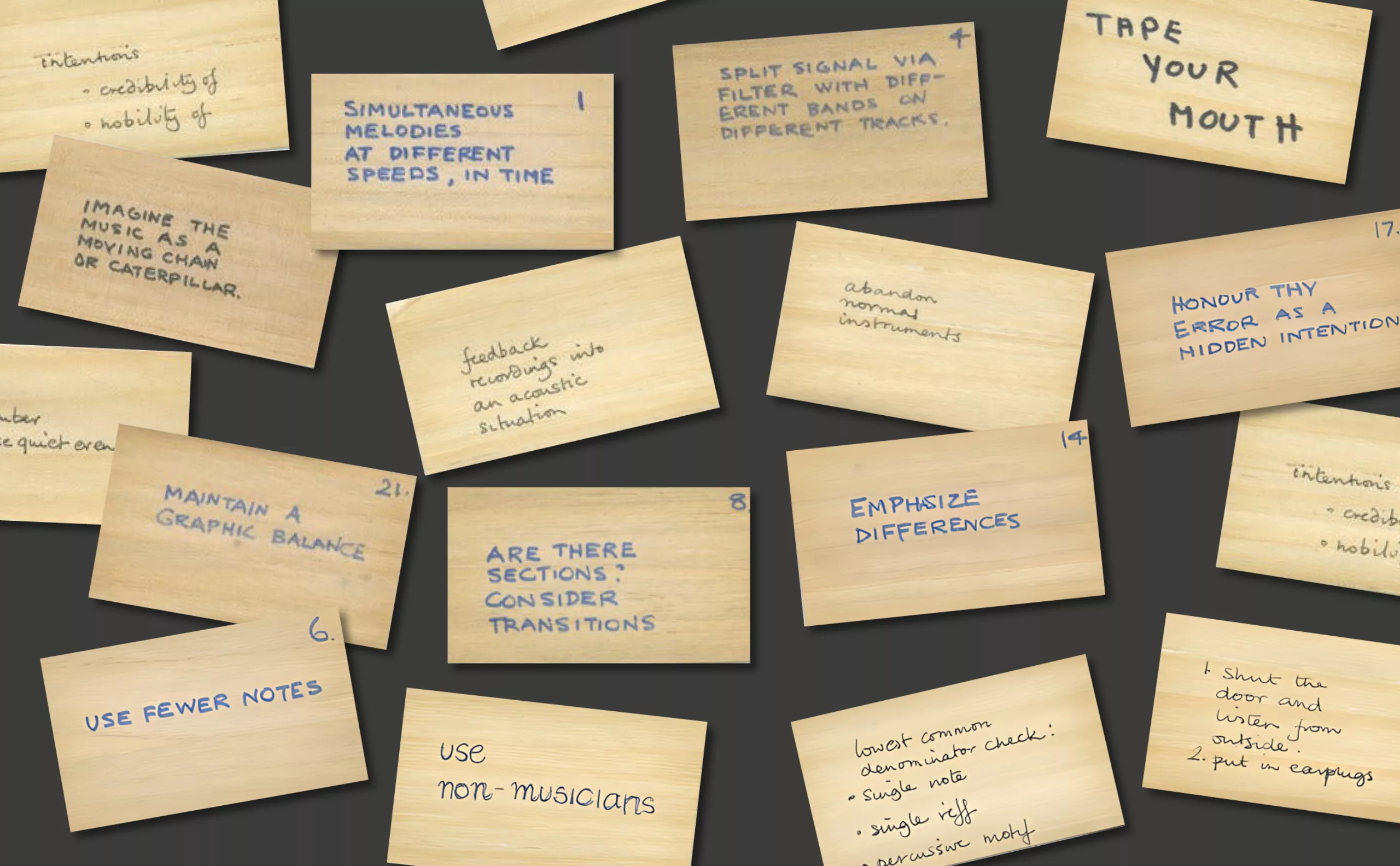

The logic seems to be the same when faced with a blocking situation. Each time, a card is used to change the angle of reflection. The idea is to be able to use these phrases as keys to unlock a creative situation, and to say to ourselves, “What if I tried something else?” It’s not so much about getting an answer to a question, as discovering and understanding a range of possibilities. Invoking chance, accident, randomness or the involuntary.

“The situation is blocked, I draw a card to move the process forward… I accept to make a mistake or to be surprised by a path I hadn’t foreseen. To continue, to get out of the lock-in, I need to welcome “controlled letting go”. “I can draw a second or third card, which will echo the first…”

Don’t be afraid of things because they’re easy to do

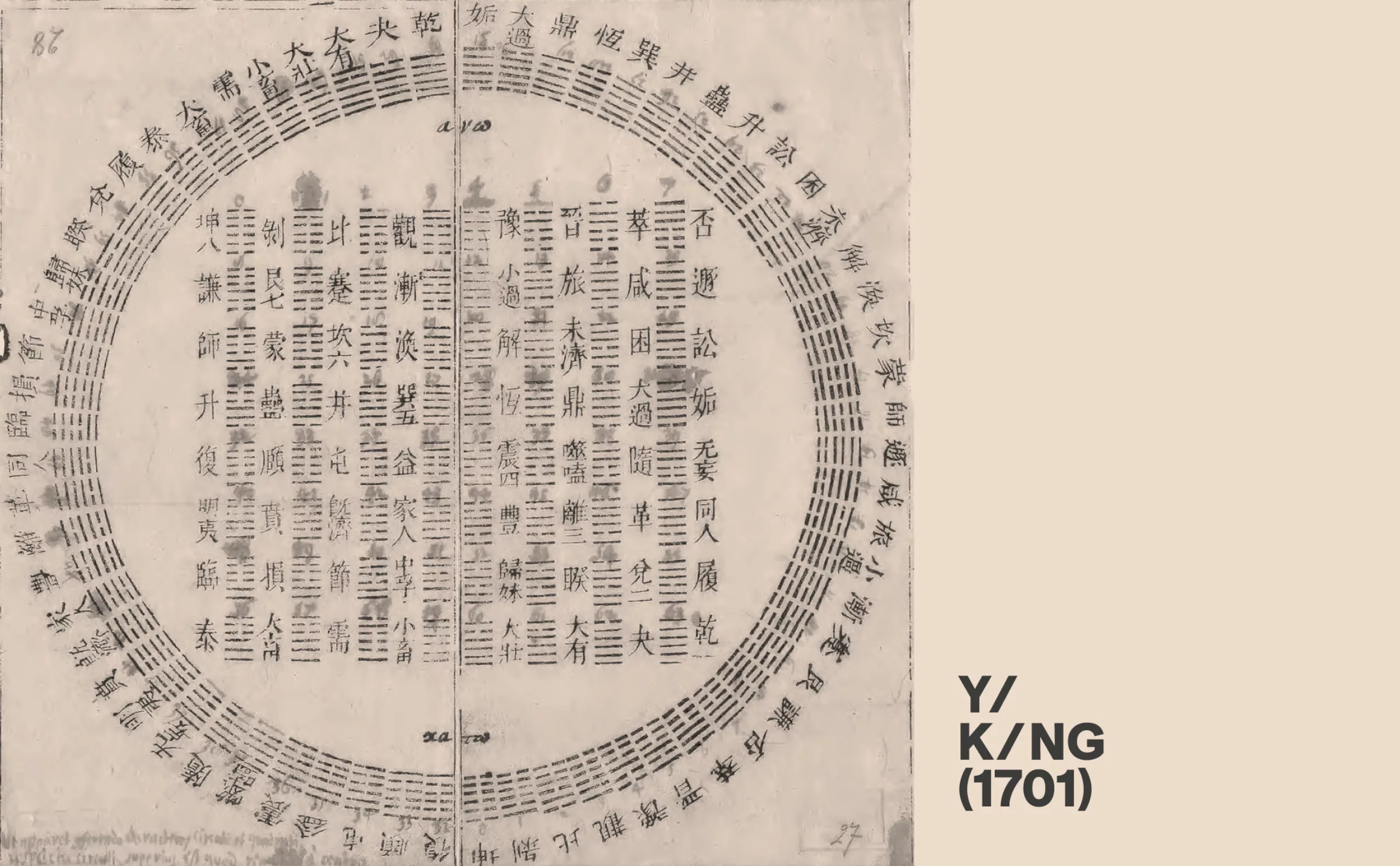

The essential reference, often cited by both artists, is the “Book of Changes”, the “Yi King”, one of the oldest Chinese texts. A construction based on binary signs that can be adopted for divinations.

The I Ching does not predict the future, but describes what is in germ in the present, and therefore the different futures that could arise from it. The book has long been used as a decision-making and governing tool.

In the 20th century, a number of Western artists seized upon it. Foremost among them was Philip K. Dick, who discovered the book through his reading of Jung. In contemporary music and dance, John Cage and Merce Cunningham used the I Ching as a basis for their work.

In the late 1940s, Cage’s ideas of order began to give way to ideas of absence of order. Random operations soon became part of the creative techniques of both choreographer and composer.

There’s no doubt that Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt had the Book of Mutations in mind when they created their Oblique Strategies. In 1972, Schmidt had produced drawings inspired by the hexagrams of the I Ching. Brian Eno, for his part, had been interested in Cage’s music from an early age and couldn’t escape the Chinese oracle.

Brian Eno and Peter Schmid will finalize a first card set of “113 worthwhile dilemmas”: “Oblique Strategies – Over one hundred worthwhile dilemmas”.

The print run is limited to 500 copies. Various editions were produced, with the number of cards ranging from 100 to 128.

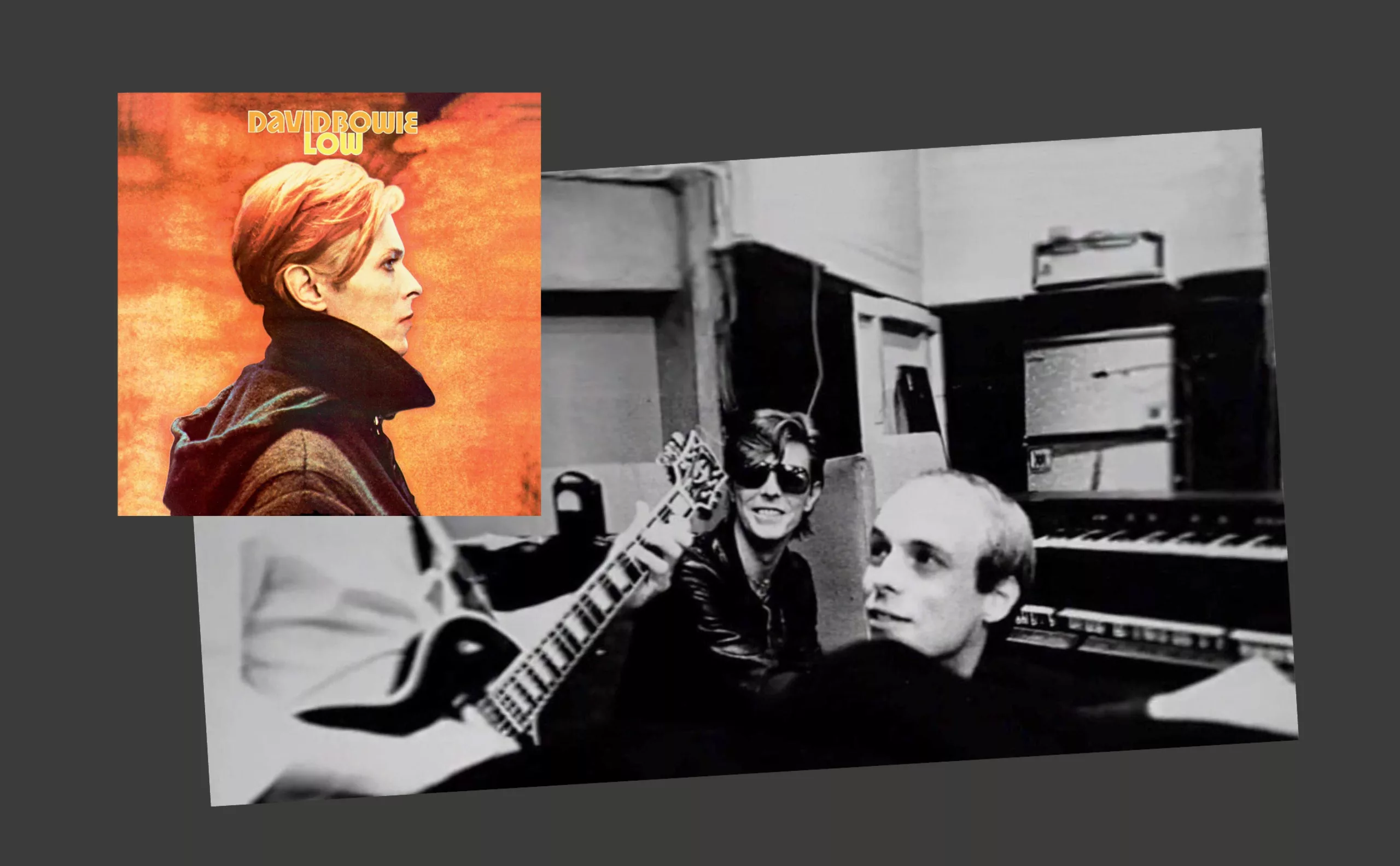

In 1975, Brian Eno was called to Berlin to produce “Low”, the first album in David Bowie’s Berlin trilogy (“Low”, “Heroes” and “Lodger”). All the music critics consider these three albums to be nurtured by impressive creativity and unexpected risk-taking.

Legend has it that Brian Eno used “Oblique Strategies” during the recordings. Provoke chance, draw a card, bounce.

At the same time, he produced Iggy Pop’s first two solo albums, “Lust For Life” and “The Idiot”. Two seminal albums in the Iguana’s career.

A few years later, Eno collaborated with U2. He went on to produce six albums by the Irish band, who remained less sensitive to the risky cards played by “Stratégies”.

More recently, Phoenix and MGMT have also declared that they use Eno’s cards in the studio.

Stumbling blocks are a necessary part of any creative process, whatever the field.

More than 40 years after they were first published, the “Oblique Strategies” remain a highly effective tool for stimulating creativity.

Because, unlike many self-help books, the “Oblique Strategies” are not based on poetic advice or aphorisms. It’s very concrete. You can put it into practice immediately.

There are no equivalent “Oblique Strategies” for graphic design, but Eno’s could easily be appropriated and personalized. Here are a few suggestions…

- Discover the recipes you use and abandon them

- Use an unacceptable color

- Go backwards

- Remove elements in order of apparent importance

- Try to state the problem as clearly as possible

- Honor your mistake as a hidden intention

- Put it in order

- Put it upside down

- Don’t emphasize one thing more than another

- Don’t be afraid to show off your talents

- Look at the order in which you do things

- Be dirty

- Use an old idea

- You don’t have to be ashamed of using your own ideas

- Don’t be afraid to show off your talents

…and to conclude, don’t hesitate to “take a break”, the advice every creative person knows.

In a 1998 speech at the Virgin Megastore on the Champs-Elysées, Brian Eno returned to the importance of randomness as a creative spark.

“Computers are a reflection of the people who developed them. And the men who developed them live entirely in this part of their body, the head.

When I say computers aren’t African enough, I mean they don’t involve any part of our body in a physical rhythm, in an exciting way… You know, we’ve got this thing here called our body, which took three million years to get to where it is today and works really well. And now we’ve come up with this machine that’s only 25 years old and we’ve completely abandoned this tool, the body. It’s completely idiotic. I work with computers all the time and I can’t stand them. I feel like I’m dying when I use them.

You know why people who work with computers all the time are always into extreme sports or sado-masochism? It’s because they don’t use their bodies on a daily basis.

Didn’t you know that?”

The interview with Brian Eno in full:

http ://jeannoel.roueste.free.fr/techno/interviews/eno/eno.html

____

Rédaction : François Chevret