William Morris: (interior) design is not a luxury

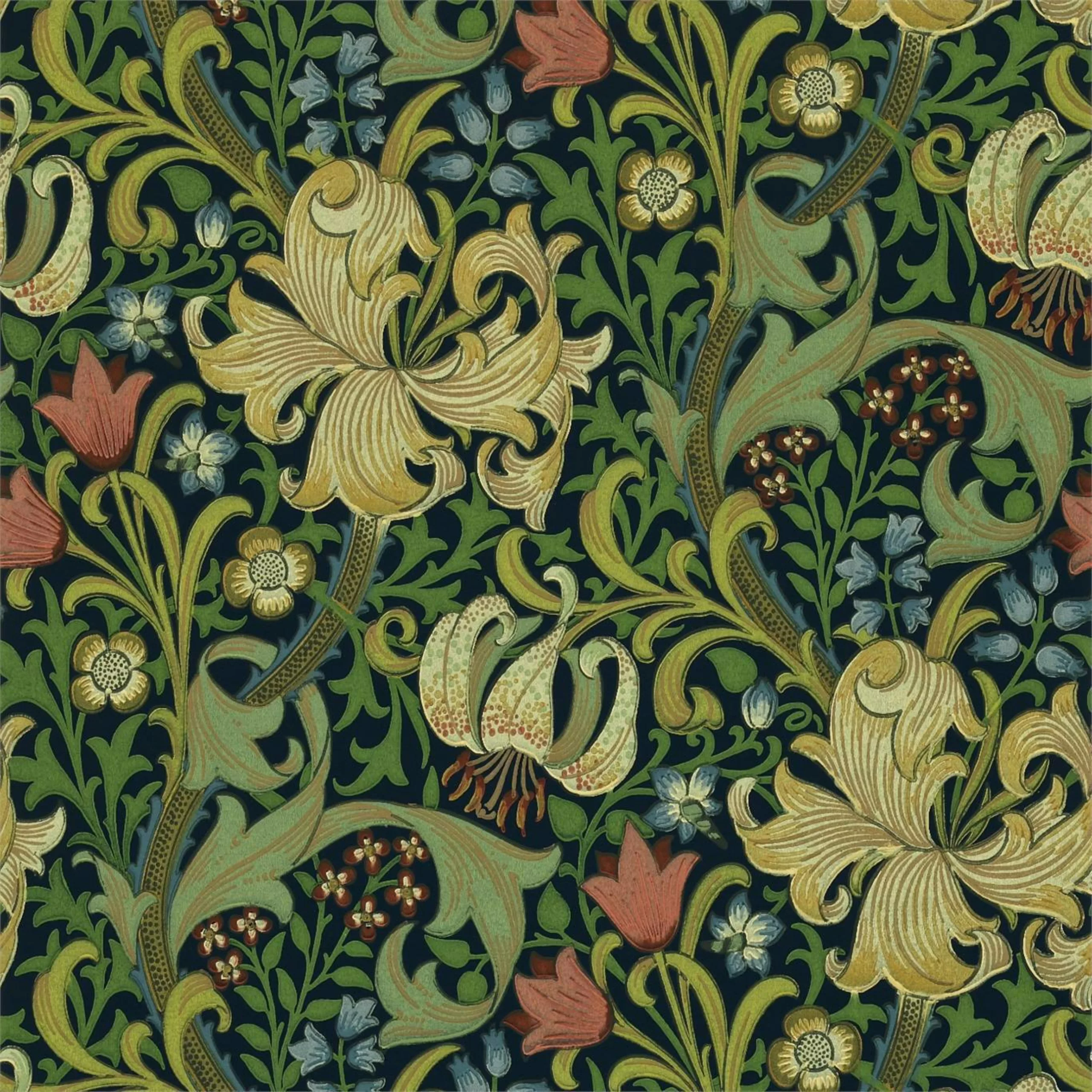

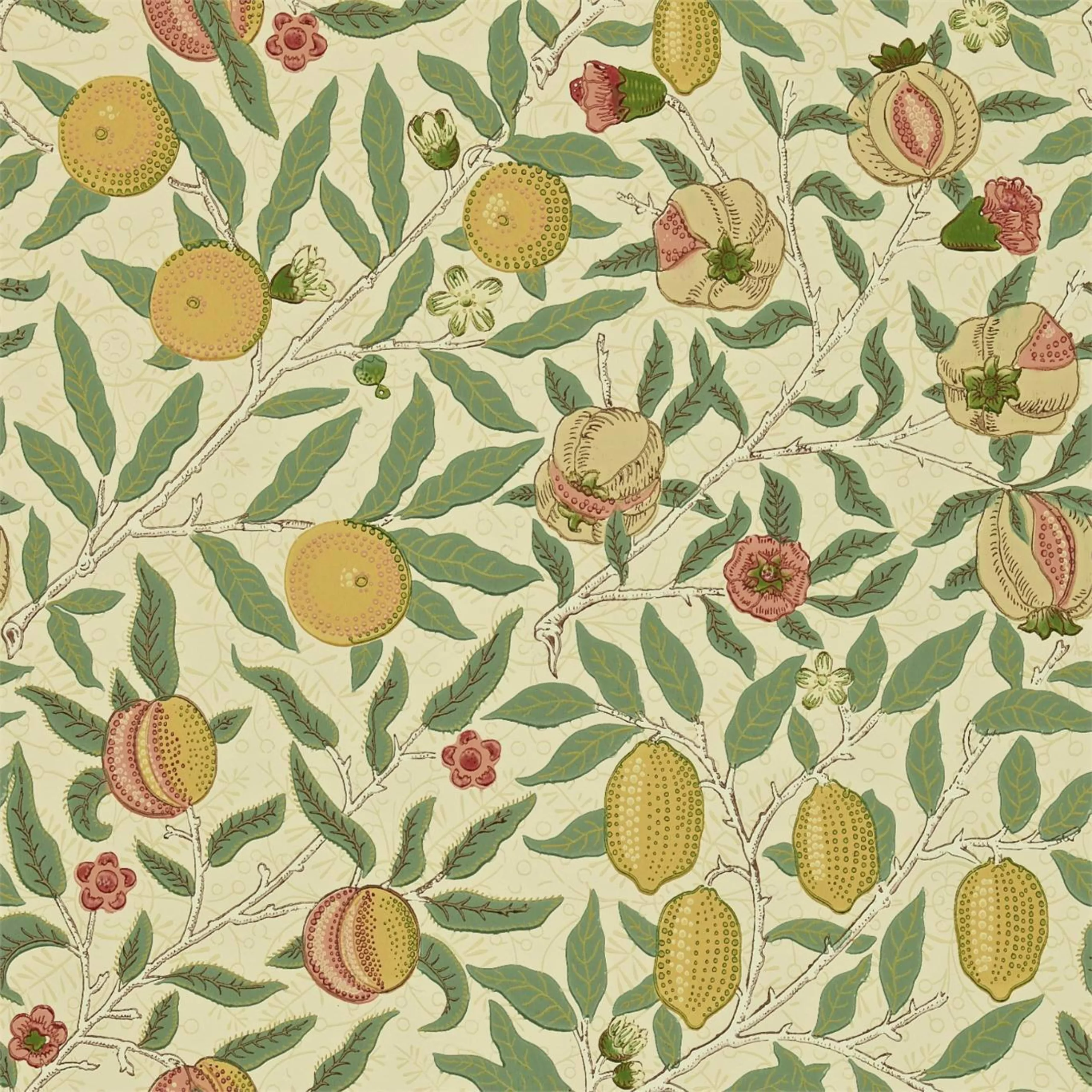

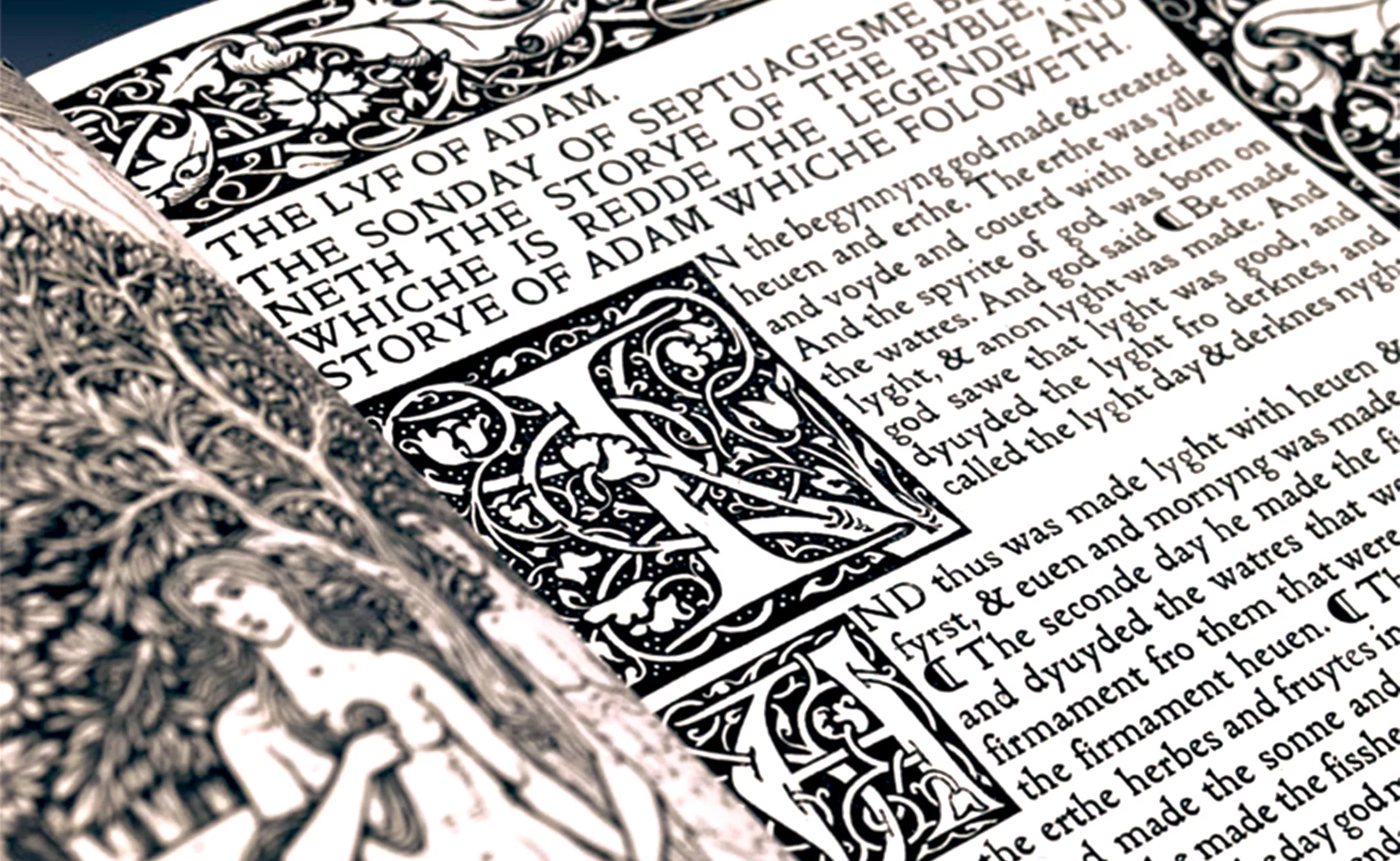

By dint of roaming the forest in his childhood, his “first master” (G. Vidalenc), William Morris will eventually introduce it into the Victorian houses of England through his pictorial motifs. Interior designer, his graphic creations of wallpapers, tiles, stained glass or fabrics depict a wild and luxuriant Eden where are mixed, in the manner of medieval illuminations, leaves, berries and local or exotic birds. “First decorator of the Modern Era“, according to historian Roger-Henri Guerrand, but also a poet, writer and activist, his work inspired by nature and designed by man is opposed to the mass industrial capitalism of the late nineteenth century. It continues to make sense today.

Valuing manual work, craftsmen and interiors

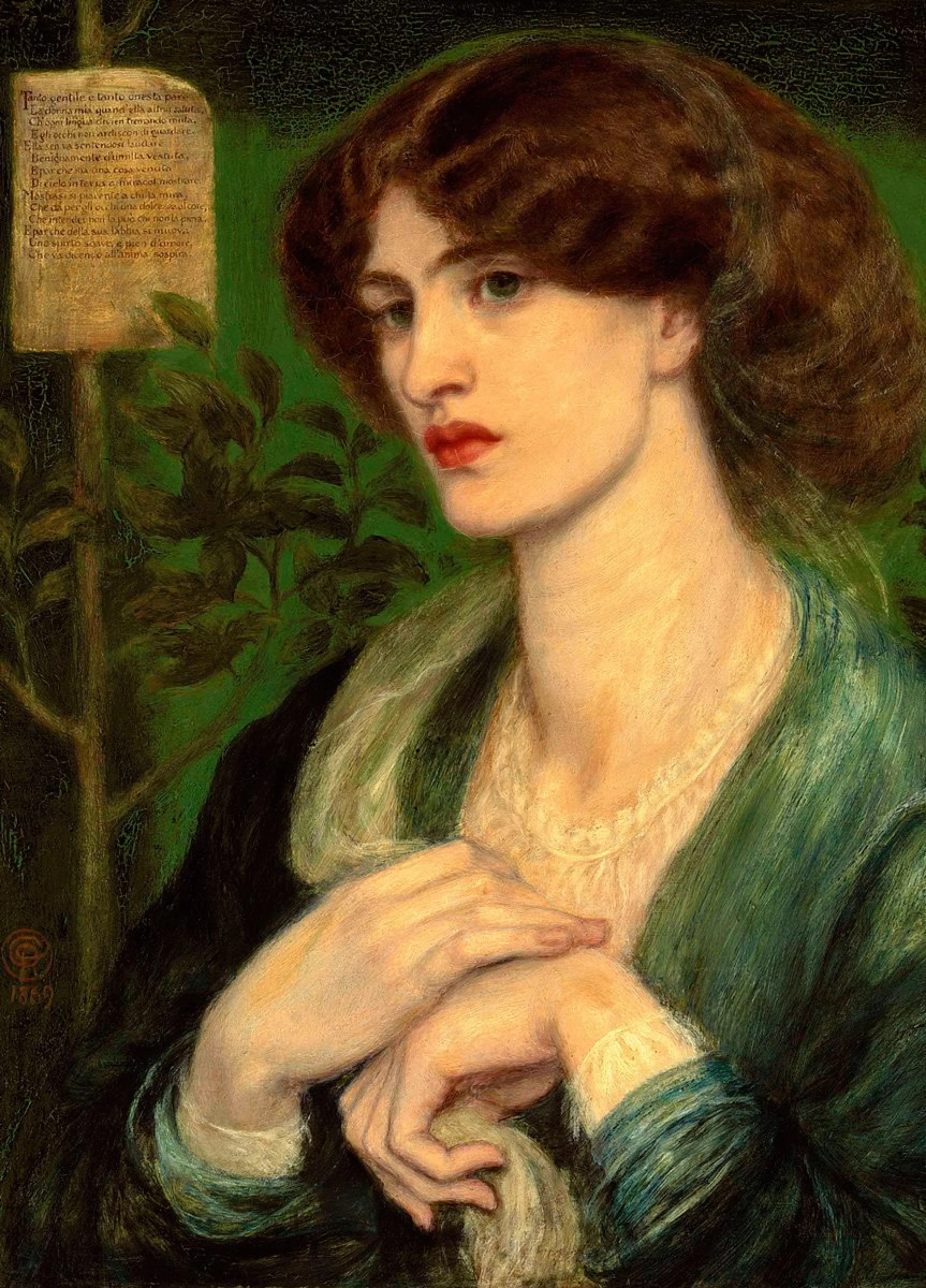

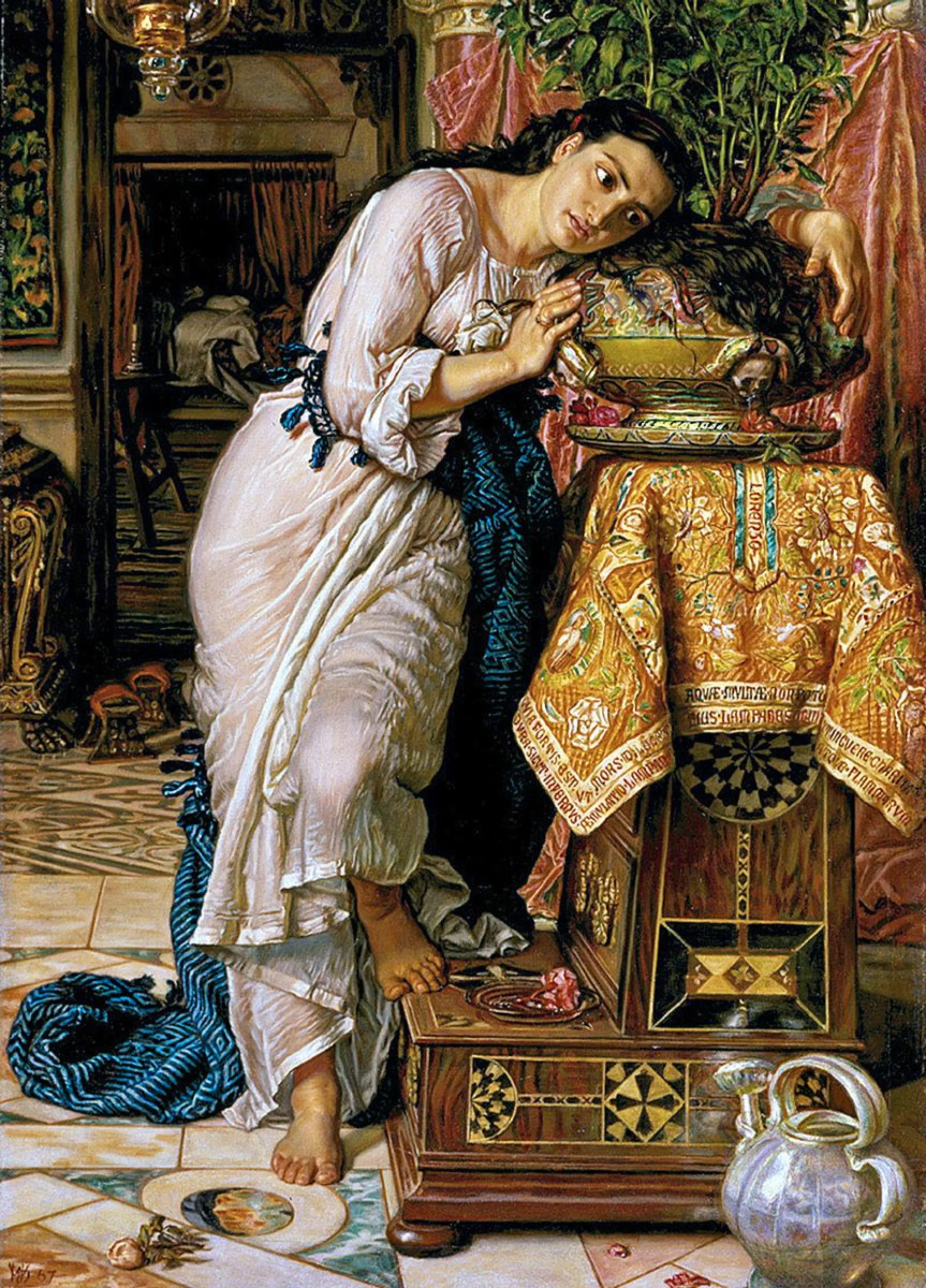

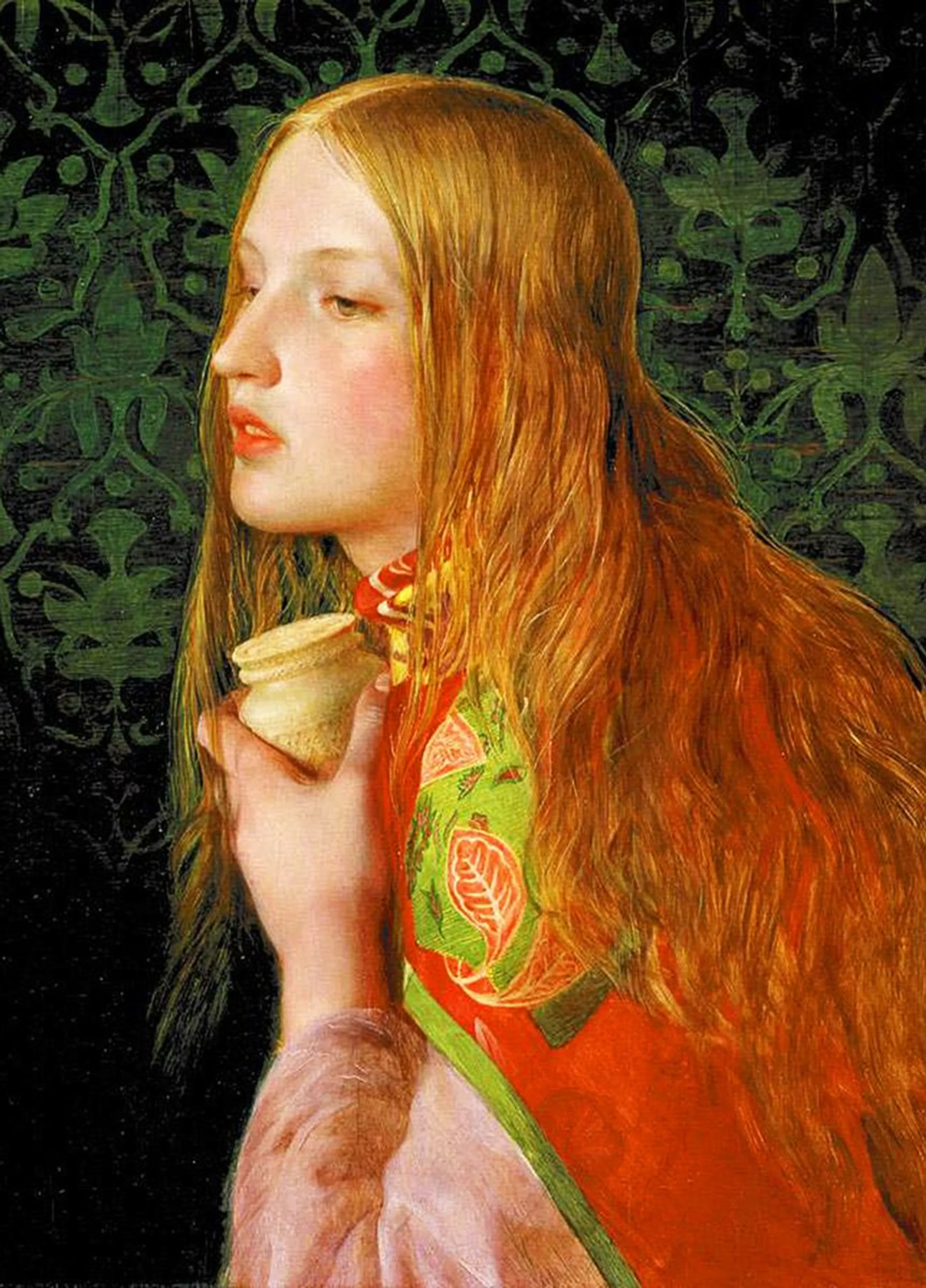

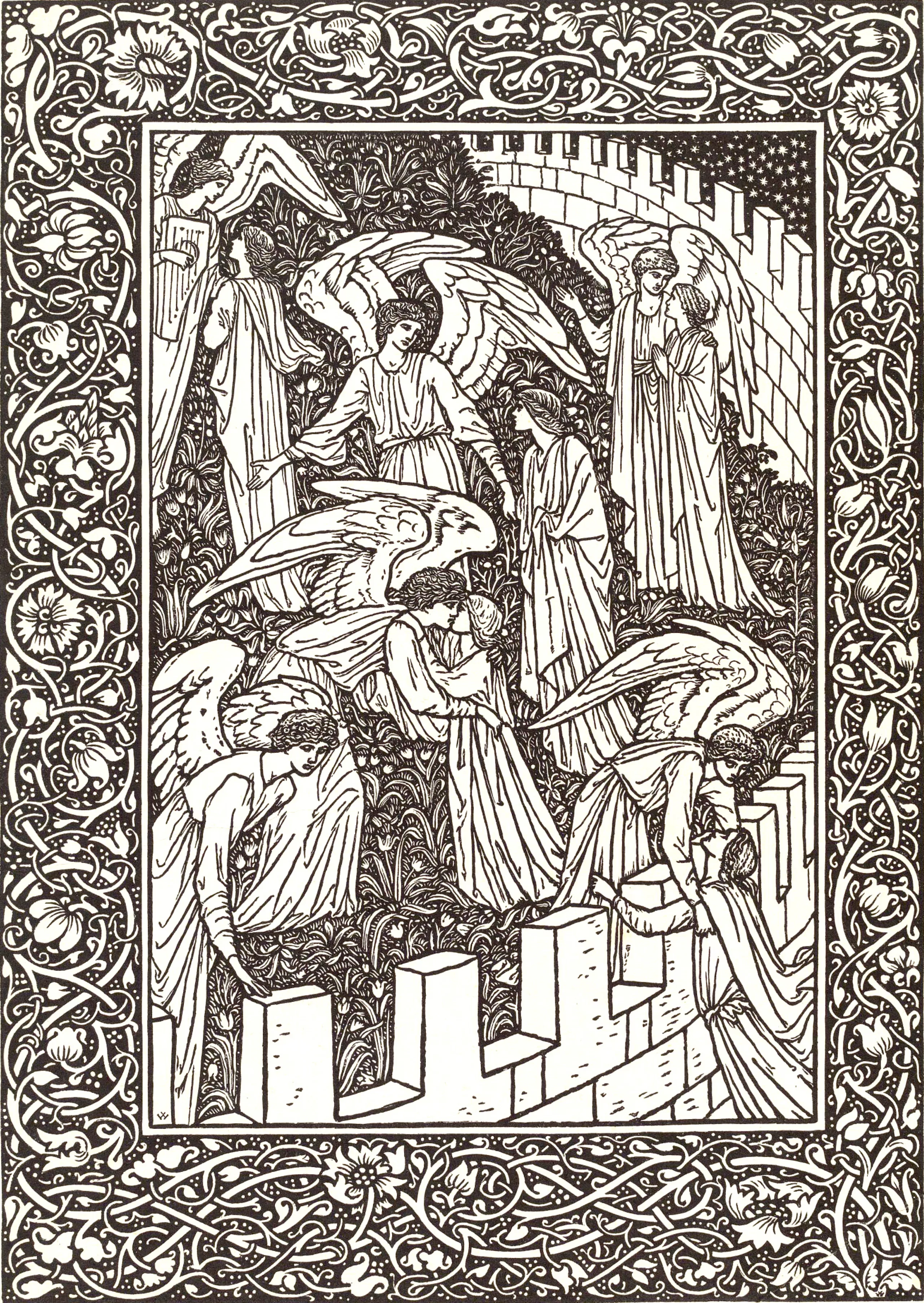

William Morris was passionate about the Middle Ages and the Pre-Raphaelite period, of which he was in contact with several adepts and artists, including his friend Edward Burne-Jones. In his novel The Map and The Territory, Houellebecq writes: “the fundamental idea of the Pre-Raphaelites was that art had begun to degenerate just after the Middle Ages, that from the beginning of the Renaissance it had been cut off from all spirituality, from all authenticity, to become a purely industrial and commercial activity.“

These artists also deplore the separation of fine and decorative arts that divides art from craft, and the loss of the status of the artist who rose freely through his creation in the lamented days of the Middle Ages. The craftsman, gradually replaced by machines, can only flourish if he invests himself fully in the realization of his work.

The machines of the British Empire -which dominates the world by its power and technology- now produce only standardized and mass-produced “cheap tat” Interiors look the same and have neither interest nor quality (a bit like IKEA today). The railroad and technology are developing at high speed and we fear to lose know-how and traditions. Inspired by the words of John Ruskin, Victorian art critic and poet refusing the modernity of the industrial revolution, Morris and the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood fear and reject the advent of the massive bad taste of the Victorian middle classes…

Faced with this growing threat, they wanted to give a new face to manual labor. Morris moved with Burne-Jones to London and, having no furniture of his own, began to design his own. This was the beginning of a long passion for interior design.

In 1861, Morris and his associates founded an interior design company that fought “against the ugliness of Victorian interiors by rehabilitating both the decorative arts and a mode of production that was both artisanal and collective, giving the artist-craftsman full control over and enjoyment of his work” (Marion Leclair, translator of W. Morris). His mission was therefore twofold: to bring art into the home (and also into churches), and to revalue the work of artist-craftsmen alienated by industry.

This artistic work, inspired by the Middle Ages, gives power back to the craftsman (alienated in factories) and must be collective. Morris & Co. creates wallpapers, fabrics, but also stained glass. Morris hoped that “each house would be pleasant and clean for its occupant, conducive to his rest and useful for his work“. He is a precursor of founding ideas that give a purpose, a utilitarian role to design, while remaining simple so that the beautiful object is sufficient in itself.

At the time of its creation, the company resurrects ancestral techniques of artisanal manufacture using specialized machines, as below the impression with wooden matrix. The artisans can produce on the assembly line, but remain skilled artists. For example, Morris brought certain weaving techniques up to date.

He spent 10 years collaborating with an English silk dyer to revive vegetable dyes, inspired by the manual technique and patterns of Indian cottons. Morris & Co. is celebrating its 160th anniversary this year.

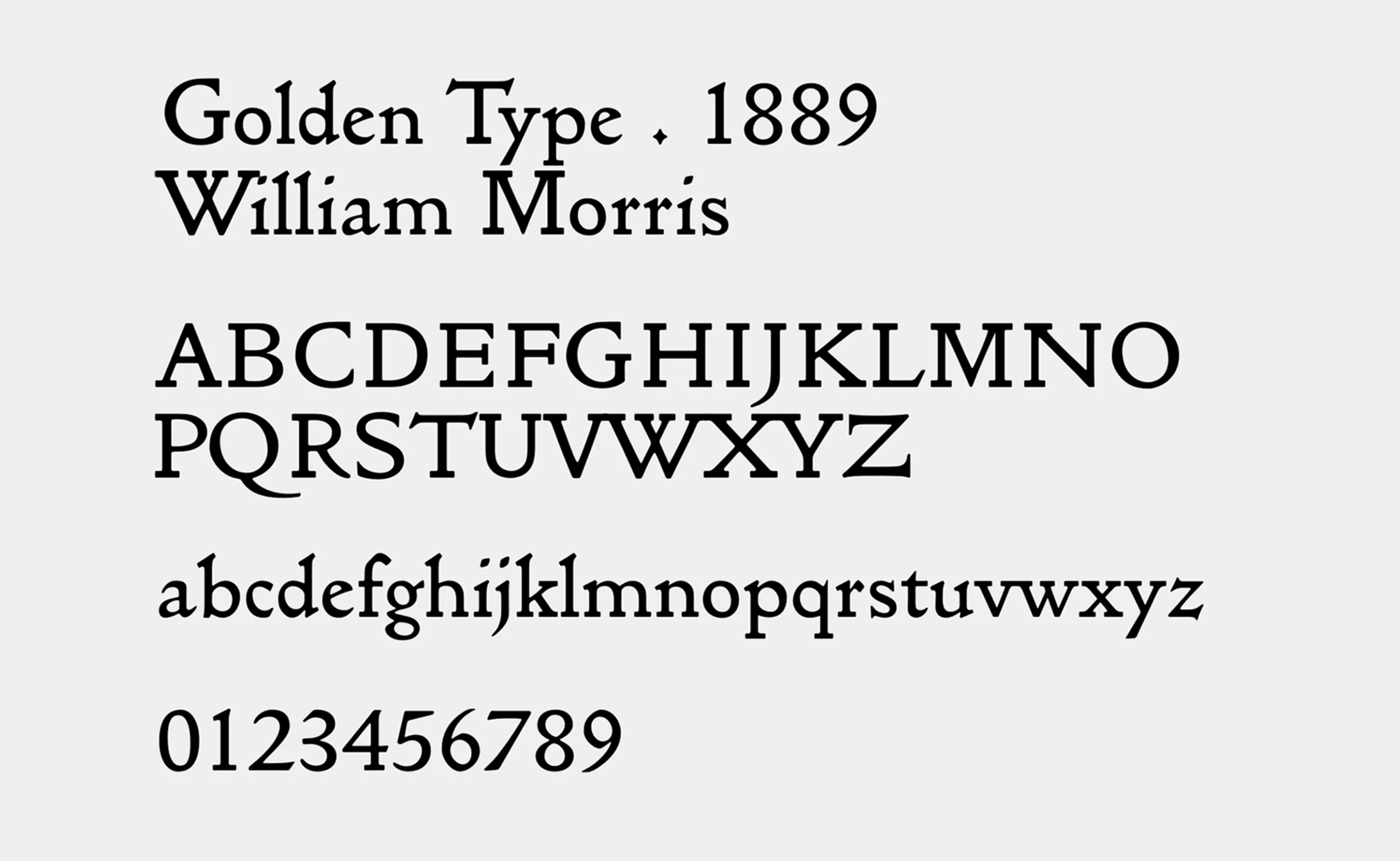

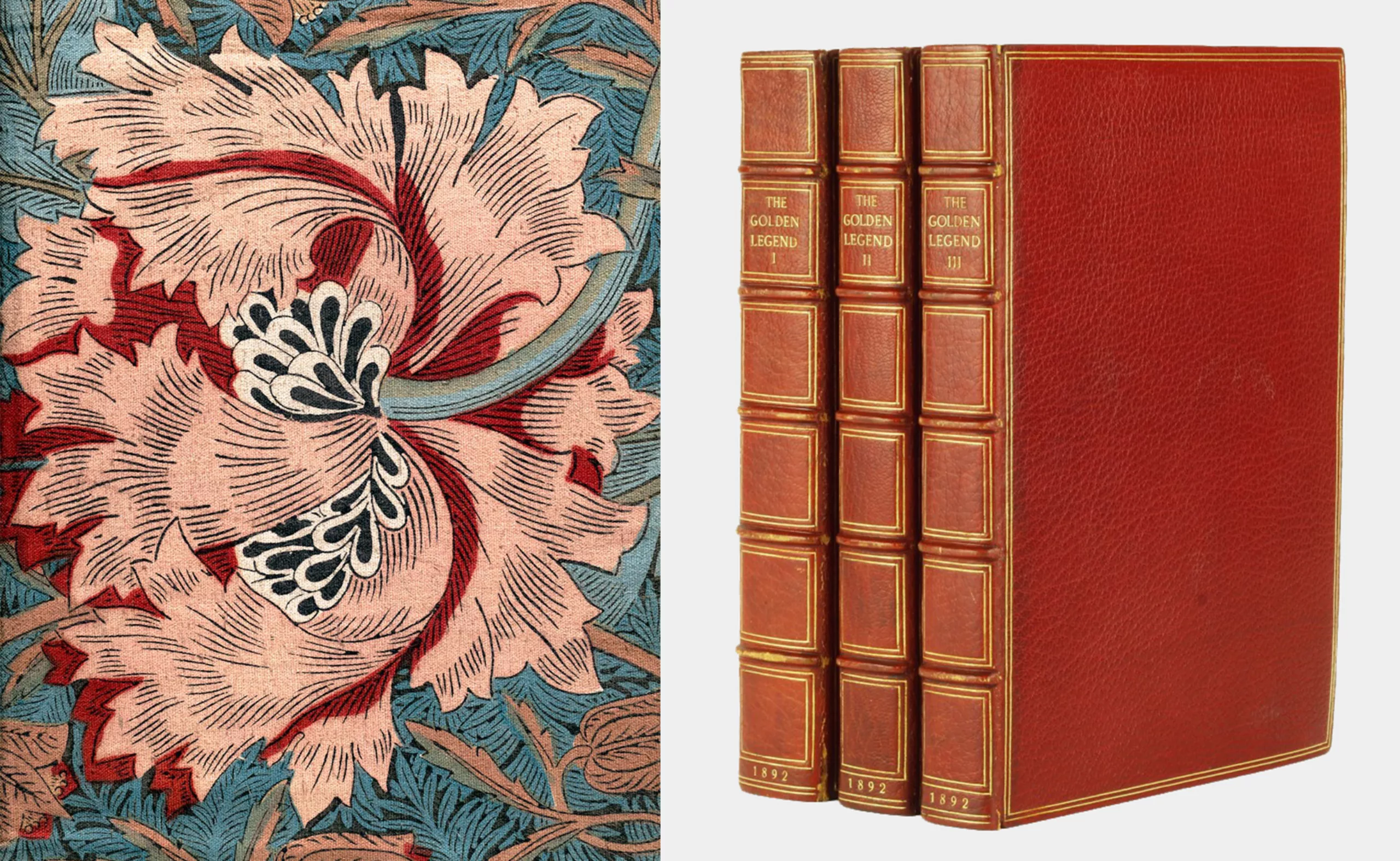

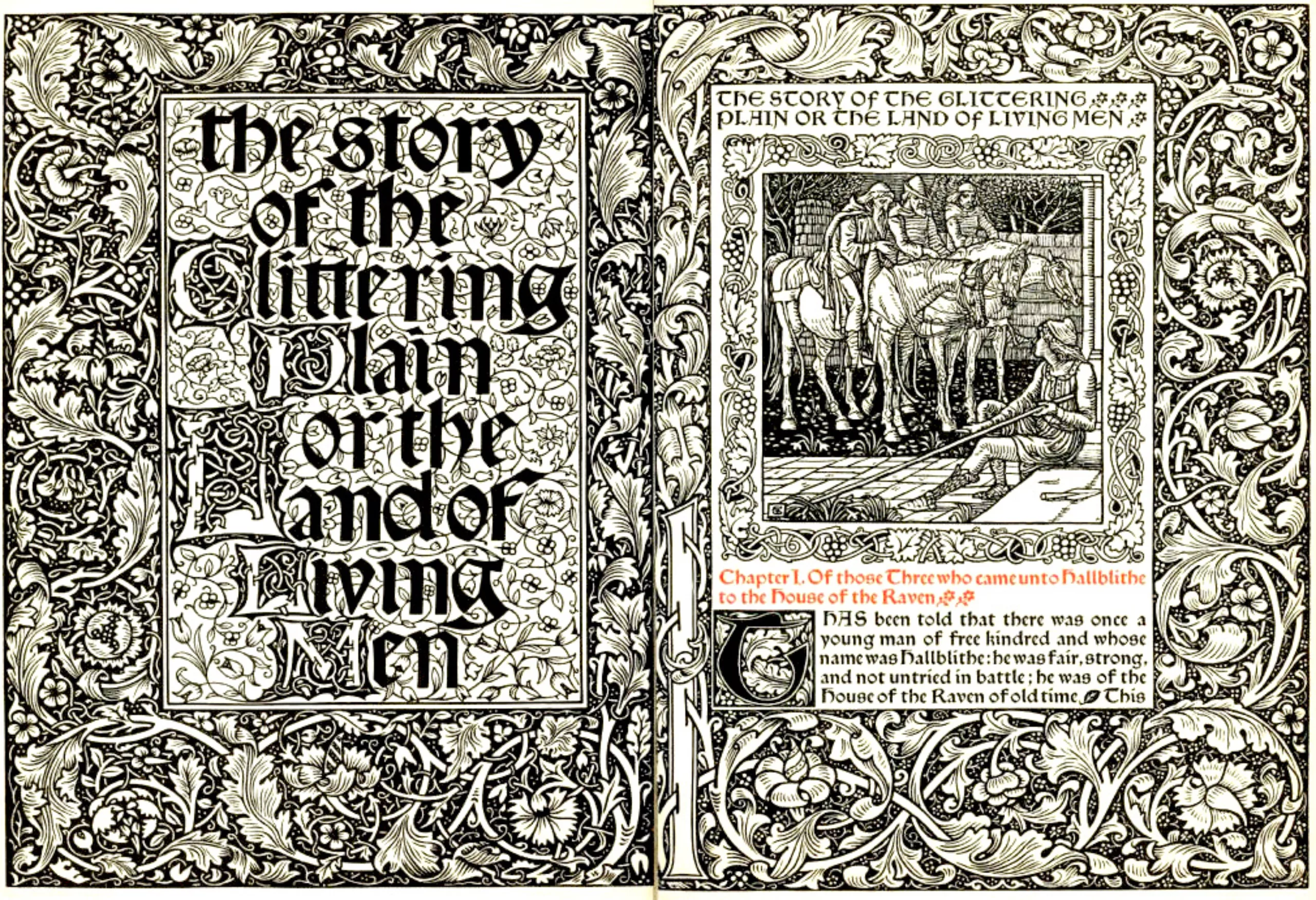

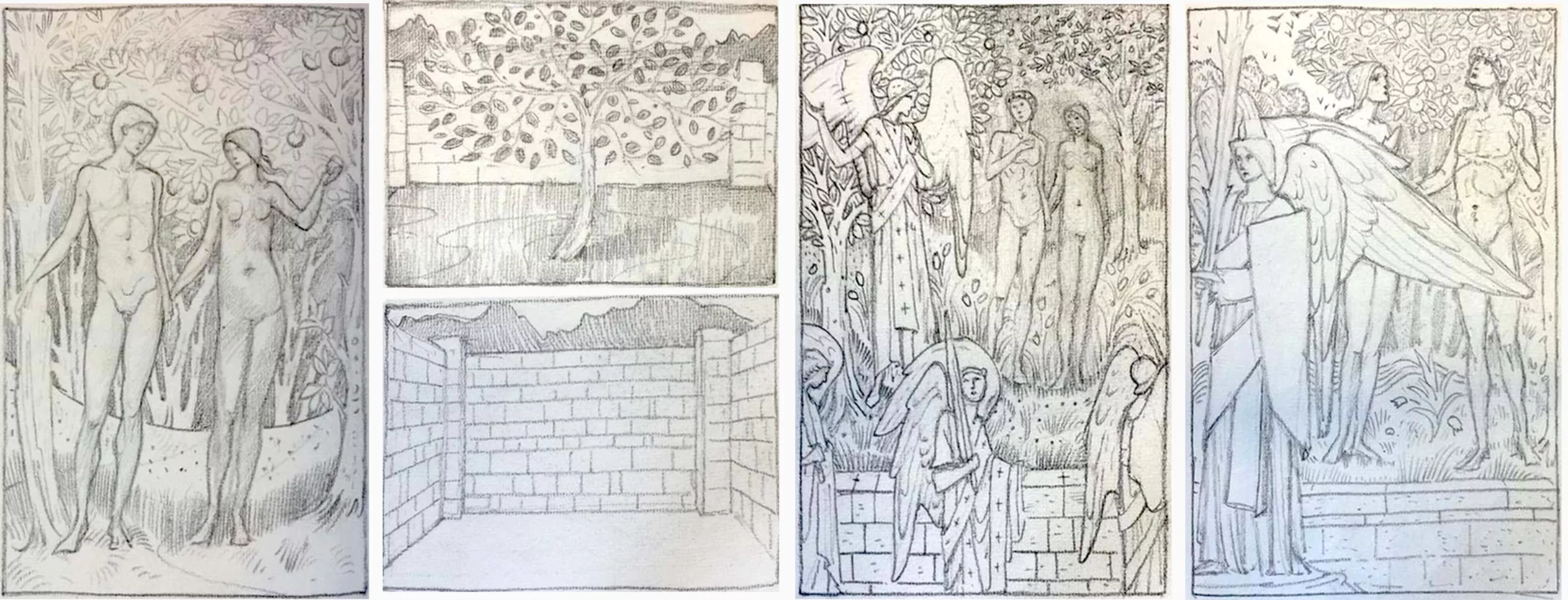

At the age of 60, he started typography and created typefaces for his publishing house, Kelmscott Press. Morris always wished to value manual work and revived medieval typefaces inspired by Nicolas Jenson (1470). He thus created the Golden Type (1891) for the publication of the book Golden Legend by de Voragine, from his collection of rare and precious books. The paper is made of linen, the illustrations are made by his artist friends or by himself and he creates ornaments and typography.

A revolutionary and militant design

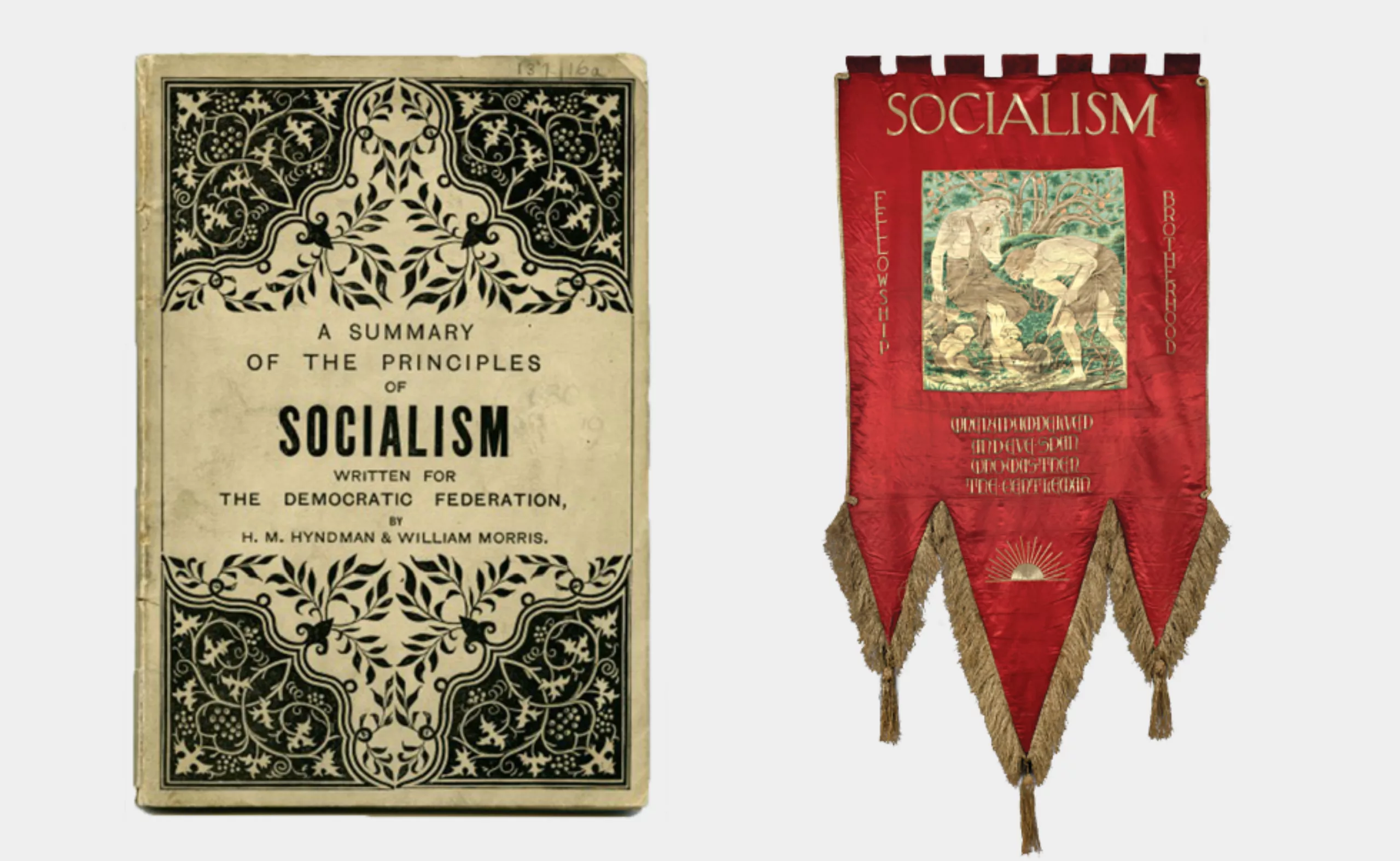

Behind this double mission lies a militant political commitment to oppose the social injustice of rising capitalism. If the ultimate value of capitalism is profit, Morris prefers to believe in beauty, usefulness, and equality in abundance. In 1883 he became involved in politics and in 1885 founded the second socialist party in England, which did not yet have many followers. Through his reading, including Karl Marx’s Capital, which he read in French before its translation, he sharpened his political sense and actively campaigned among the masses by popularizing the great revolutionary socialist texts. His thoughts still resonate in our society today, even if things have evolved (today, workers are also consumers):

“Cheapness is inherent in the system of exploitation on which modern industry is based. In other words, our society comprises an enormous mass of slaves, who must be fed, clothed, housed, and entertained as slaves, and whose daily needs compel them to produce the servile commodities whose use guarantees the perpetuation of their bondage.” Useful work versus useless toil, William Morris. By “slaves” he means workers.

When he addressed the middle and working classes in the streets of London, he advocated the improvement of the living conditions of the workers through the teaching of applied arts, leisure and education. Morris wished to free man from the alienation of useless work and give him back his usefulness through the beauty of the task. In his reflections and essays on the nature of work and how to make man happy, he put forward three principles applicable to the working class (“working class” who work, as opposed to the wealthy class “who consume but produce nothing”):

- the hope of rest, proportional compensation for the pain of labor

- the hope of the product, the utility and the value of the created object

- the hope of pleasure through work, stimulating the senses and the mind, inheritance and transfer of skills

Truly committed, he put all his wealth and his bourgeois heritage at the service of the socialist cause. His utopian thinking comes to life in a story, News from Nowhere (1890), in which he imagines the utopia of a post-capitalist England without money or trade, emancipated, adorned with beautiful clothes, interiors, objects and buildings, forged around free education and without government, around local assemblies to settle disputes, and common craft workshops.

Unfortunately, his ideal came up against the systemic limits he feared. Trapped by the high cost of his artisanal-industrial productions that he wanted to offer at low prices, he was forced to sell his creations “to the rich and their obscene taste for luxury”. Morris could not find a solution to produce beautiful and handmade products at an affordable price. His craftsmen, instead of rising to the rank of artists, were also gradually reduced to simple executors. Even if they find meaning in their work and have a certain expertise, they only reproduce on textile or paper the patterns invented by William Morris or his daughter May, who joined the family business as a designer.

A legacy in the world of art and design

By rehabilitating manual work and opposing industrial mass production, Morris is the founder of the Arts & Crafts movement. This artistic movement strongly inspired Art Nouveau in France, or Mingei in Japan, a “natural, sincere, safe, simple” craft (The Idea of Mingei – 1933). An ecologist before his time, his thinking led to the development of garden cities in Great Britain, thirty years before France. The notions of artist-craftsman and beauty serving the useful in the world of design strongly inspired Gropius, who later gave birth to the Bauhaus movement. In another register, William Morris is also the father of the Fantasy writing style and his novels inspired authors like Tolkien (the Lord of the Ring saga) and Lewis (The World of Narnia). Another great name in design!

PS : We swear, next time we’ll talk about a woman.

Sources :

- Le Monde Diplomatique : William Morris, un esthète révolutionnaire

- Télérama : Comment le design est entré dans nos maisons ?

- Cleveland State Art (images)

- William Morris Gallery (historique et collections)