Hobo signs, the secret language of America’s wanderers

Resourceful and itinerant, the hobos developed a secret language system, doomed to disappear, to leave clues for their fellow hobos.

Hobo Signs, inscriptions by road vagabonds

At the end of the 19th century in the United States, hobos crisscrossed the American territory from East to West, propelled by the expansion of the railways and driven by precariousness, often forced by times of crisis. Homeless workers, they set off in search of seasonal jobs provided by agriculture and the nascent industry of American capitalism, illegally hopping on trains. Vagrants were not welcome in most cities, and were regularly chased away by the police or dragged off trains. By 1911, there were an estimated 700,000 hobos in the United States. Resourceful and penniless, they developed a language system inscribed near passing places, destined to disappear, to inform their fellows of the good and bad surprises they might encounter on the road, or simply to mark their passage.

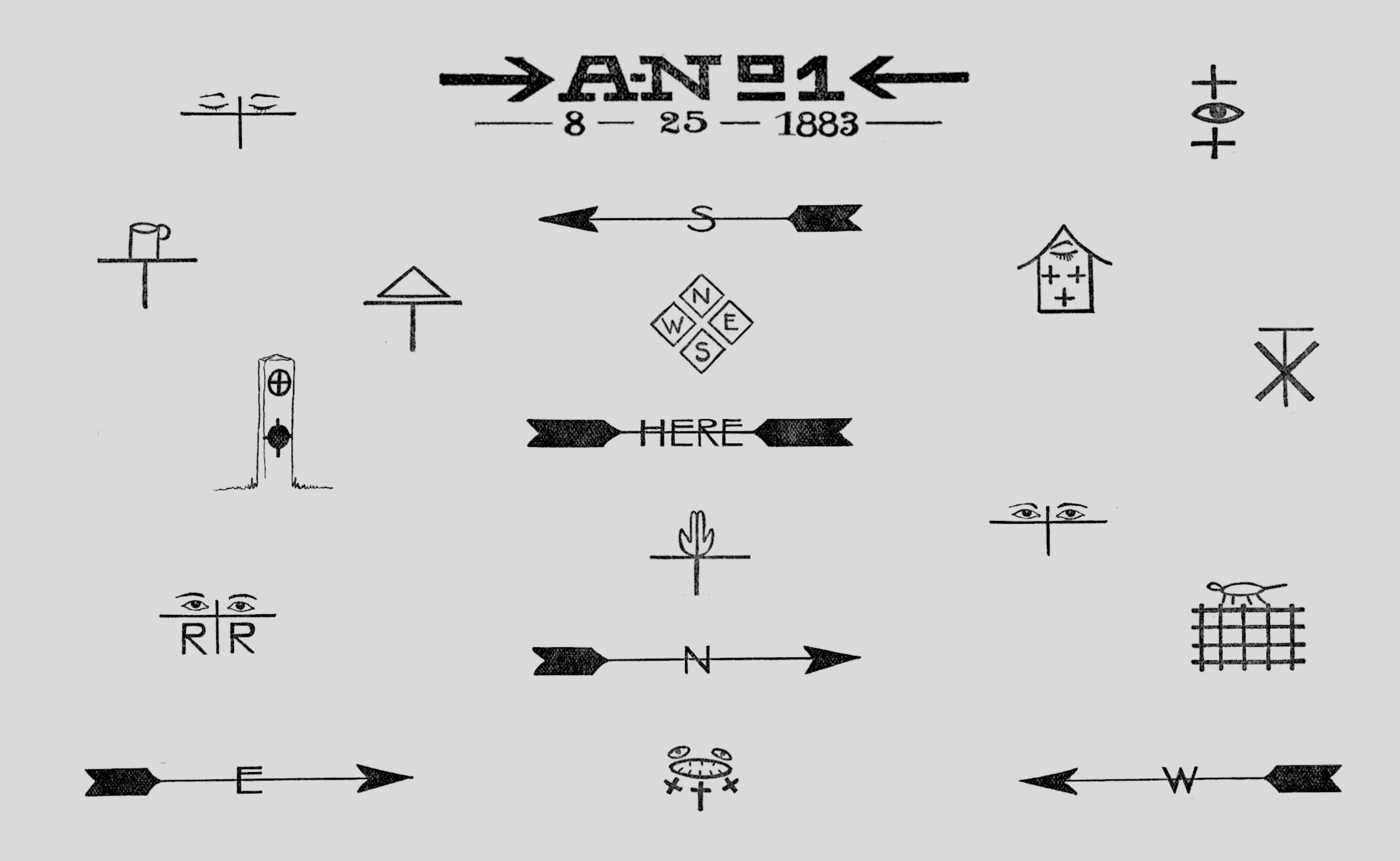

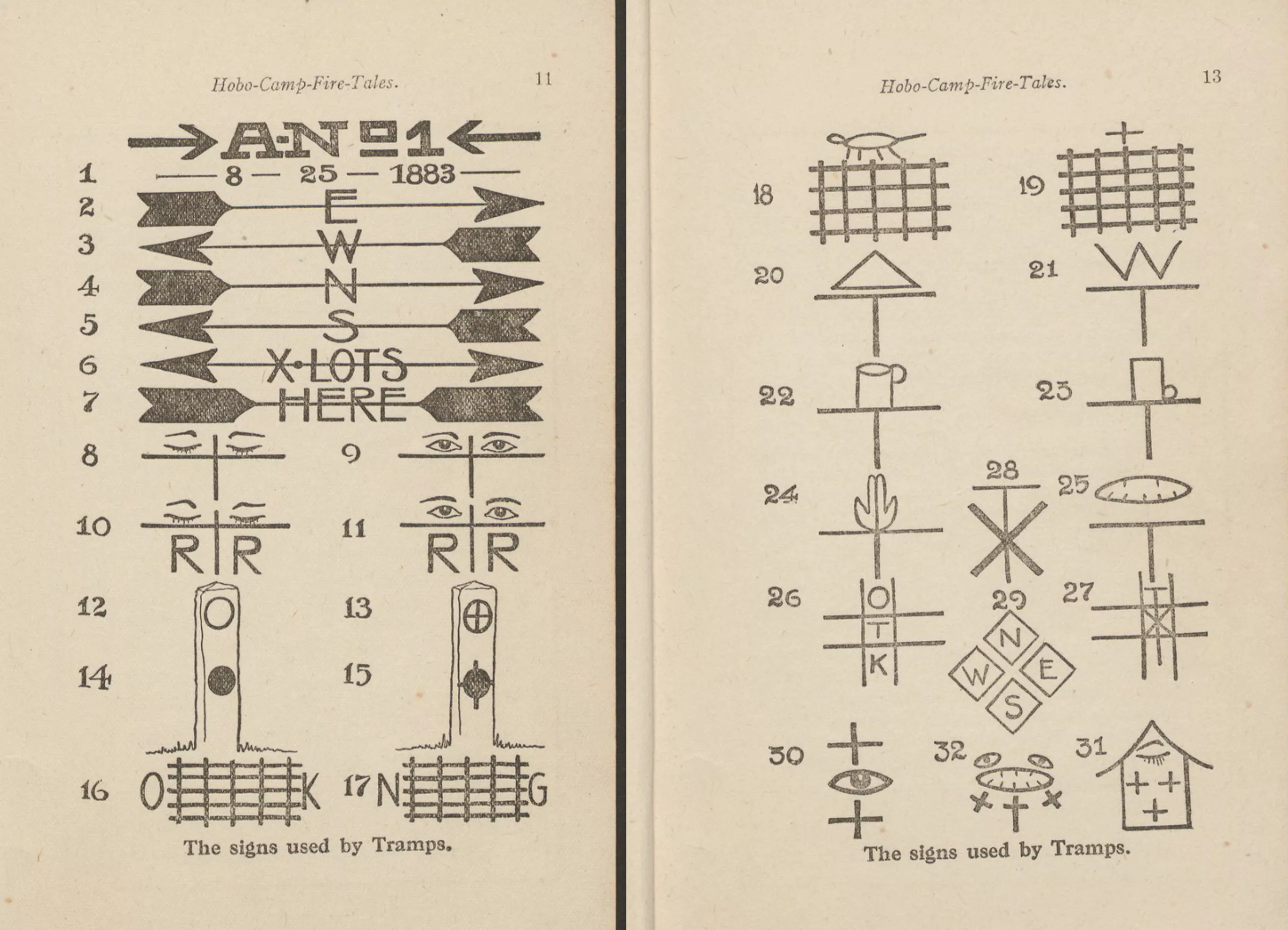

Wanderer A-N°1″, self-proclaimed “the most famous of hobos”, recounts his adventures in his book The ways of the hobo, in which he deciphers some of these signs. He explains that wanderers are “governed in their relationships by unwritten laws and rules, which they respect far more than the laws dictated by ‘society’, which they describe as annoying”. Of course, it’s questionable whether he’s being honest, or at least whether this is a non-exhaustive list, given that these acronyms are supposed to remain secret. There are symbols that mean, for example, “if you’re sick, this person will take care of you” or “filthy prison” (some hobos in need of food would willingly spend a night in prison to keep warm and have something to eat).

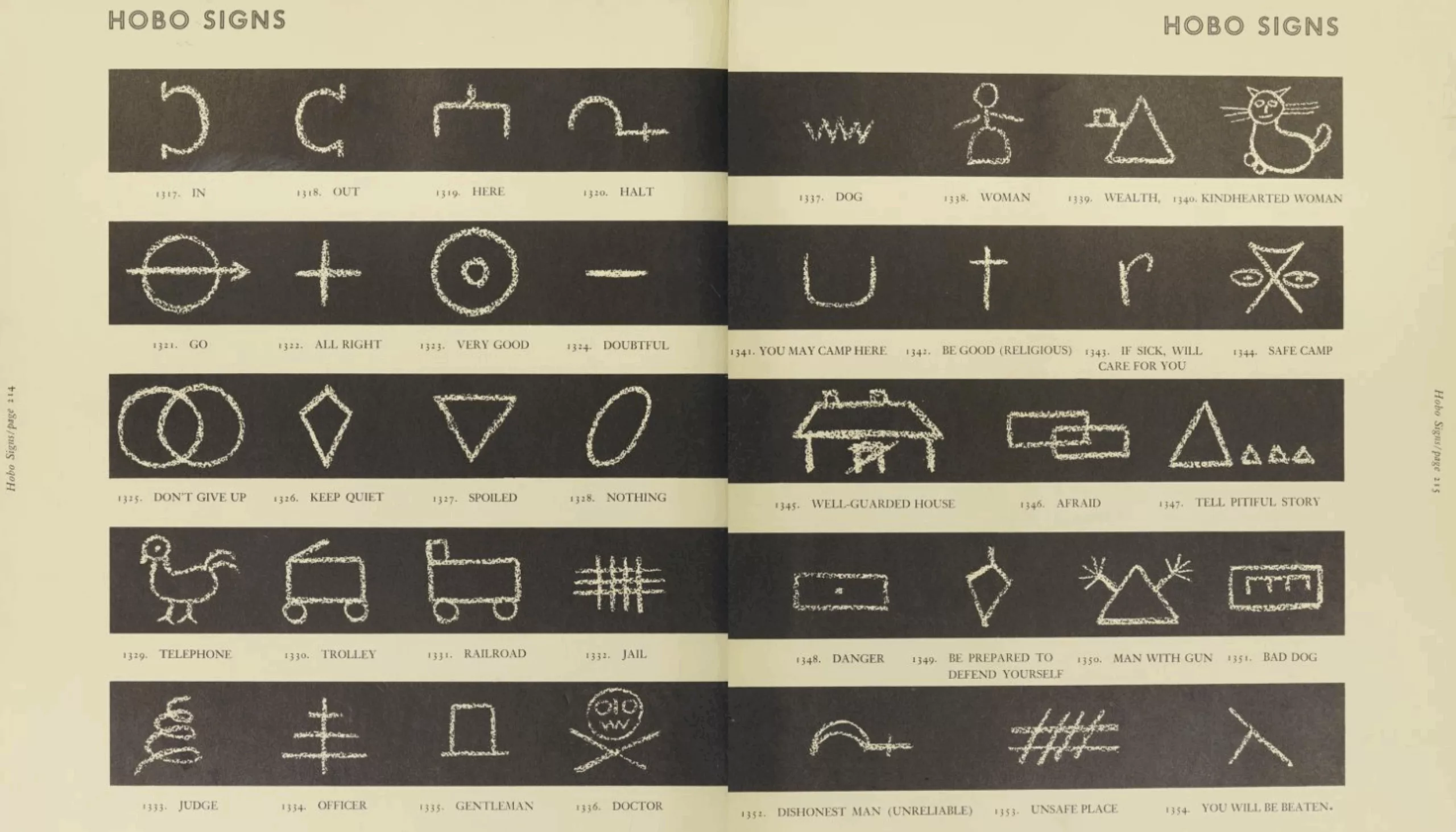

Decoding the secret language of hobos

The cat on the right above, for example, indicates a “good-hearted woman”, the four triangles two lines down advise you to “tell a pitiful story”, and the hen on the left indicates a telephone. Below, in the first line, we decipher the complete “blase” of a hobo: his name “A-N°1”, his direction “east-west”, the date of his voyage “August 25, 1883”. The “x-lots” indicates a direction and that he intends to take the back roads. 7 indicates that the wanderer is waiting in town for the person whose name is written below the inscription. Symbol 8 means the police are easy to coax, while symbol 9 means they’re ultra-hostile with their eyes open. In 10, a railroad guard is on the prowl, but he’s a “good guy”. In 11, he’s ultra hostile. Signs 12 to 14 are inscribed near houses; in 12, he indicates people with good backgrounds, in 13, people who give nothing away. 14 indicates a crazy old lady or a naughty bulldog, 15 an angry man or a vicious dog.

Figures 16 to 19 indicate a clean prison (with a grid) with well-fed prisoners, or that they are starving their prisoners. The prison in 18 is full of vermin (we see a rat), and the cross indicates that it will be contaminated with serious diseases that infect all of the United States. Acronyms 20 to 28 indicate the state of the city. The 20 says there’s a pile of rocks (to be broken), the 21 has a hospice, the 22 speaks of a saloon, the 23 doesn’t serve alcohol (prohibition), the 24 is pious, the 25 is full of hoodlums, be careful. In the town indicated in 26, you can ask for alms or work in the street, but not in 27. The city indicated in 28 is to be avoided at all costs. The diamonds in sign 29 are combined with other signs to indicate the cardinal points of other towns. 30 indicates a detective tracking down hobos in town. The 31 indicates that it’s possible to spend the night in the warmth of the prison, and the 32 indicates a hostile chief of police to flee from.

Although the real signs of the hobo language were probably kept secret to avoid making it easier for the police to find them, over time they evolved into simple “blases”, first placed near makeshift camps and then directly on trains. City graffiti is the worthy heir!

This video from the Vox channel explains a little more:

If you’re interested in this kind of pictorial writing, we invite you to read our article on pictographic and visual writing, from Sumerian to Russian Suprematism, via isotype and emojis. Or take a look at our article on pasigraphy, the universalist script invented to communicate between all cultures and readable in all languages! And to find out more, check out our article on street writing and demands, the branding of social movements.