A history of mascots

The Mascot, a Prestigious Talisman for Brands

If the mention of the term mascot brings to mind a kind of big, benevolent teddy bear, the term actually originates from the Provençal word “mascoto” which means bewitchment, enchantment, or witch. The Larousse dictionary speaks of a lucky charm or fetish, underlining the protective character of the mascot which would come, like a talisman, to break or protect from an evil spell! The first known use of the word “mascot” dates back to 1880, in the comic opera subtly titled “La Mascotte” by Edmond Audran. The composer stages a young turkey herder who brings luck, happiness and success to whoever possesses her (as long as she remains a virgin, of course). The mascot can therefore be an object, an animal or a lucky person, who wards off bad luck by their mere presence.

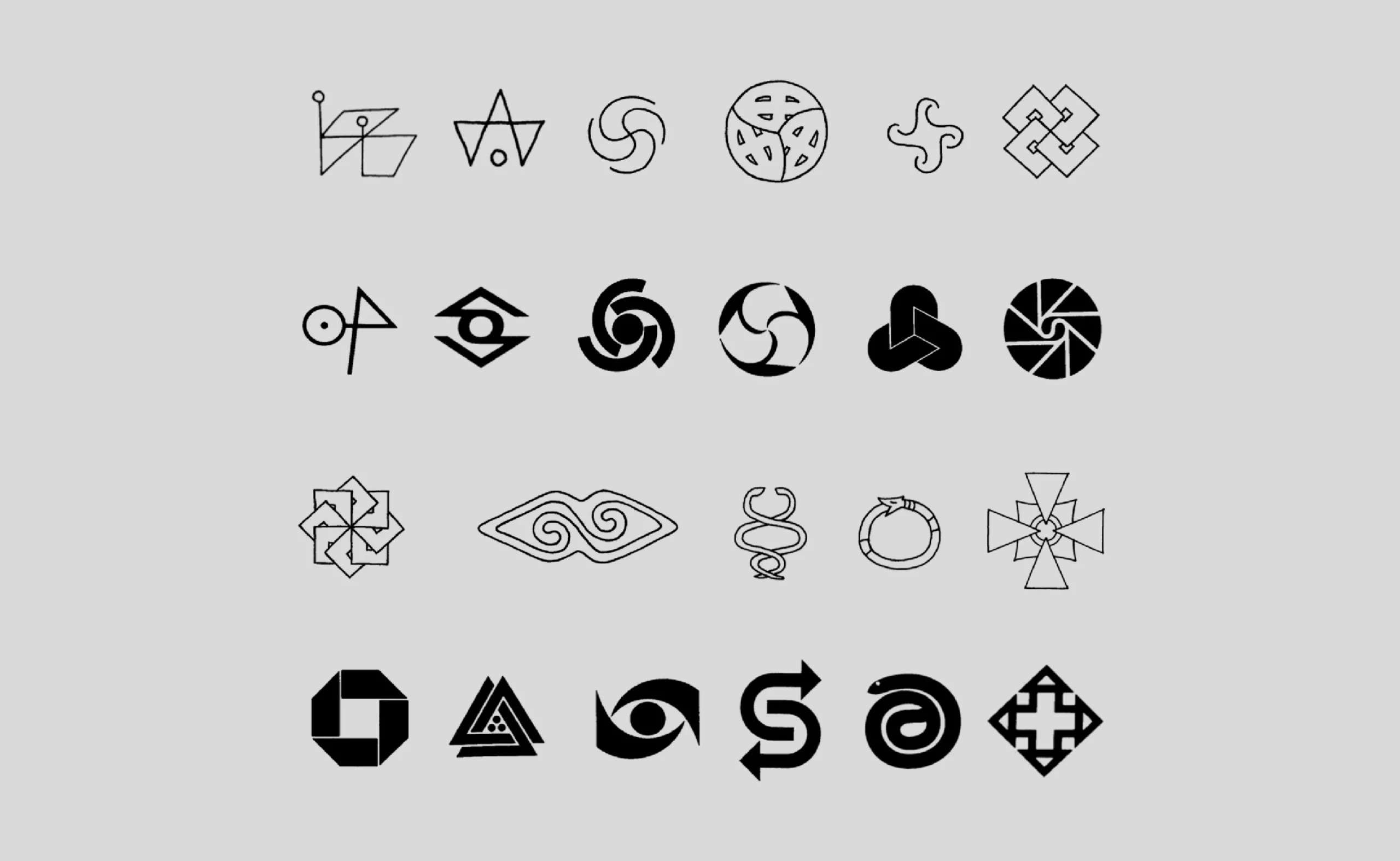

If we add to that the fact that a brand’s logo, derived from the seal, is also originally a magical symbol, a kind of protective incantation, we can better understand why brands wanted to doubly seal off bad luck. In Latin, the words “seal”, “symbol” or “signature” are contained in one word: “charactere”, an ideogram impossible to pronounce but which is understood and used to communicate, and which contains or confers a certain power to the one who possesses and applies it (Sébastien Hayez, Étapes magazine #272). Provided one is initiated into it, the brand thus exudes a certain prestige, which it can accentuate with a good mascot. We can see in this illustration some symbols from different practices or cultures around the world (thin lines), and modern logos that echo them (in bold), all taken from Adrian Frutiger’s book “L’homme et ses signes” (Mankind and His Signs).

Today, there is no more talk of witches and spells: the mascot not only brings luck (ie, in the 21st century capitalist language: increasing revenue), but above all embodies the relationship between a double (symbolically representing a community, a brand) and spectators, through intentions and a beneficial distance for all.

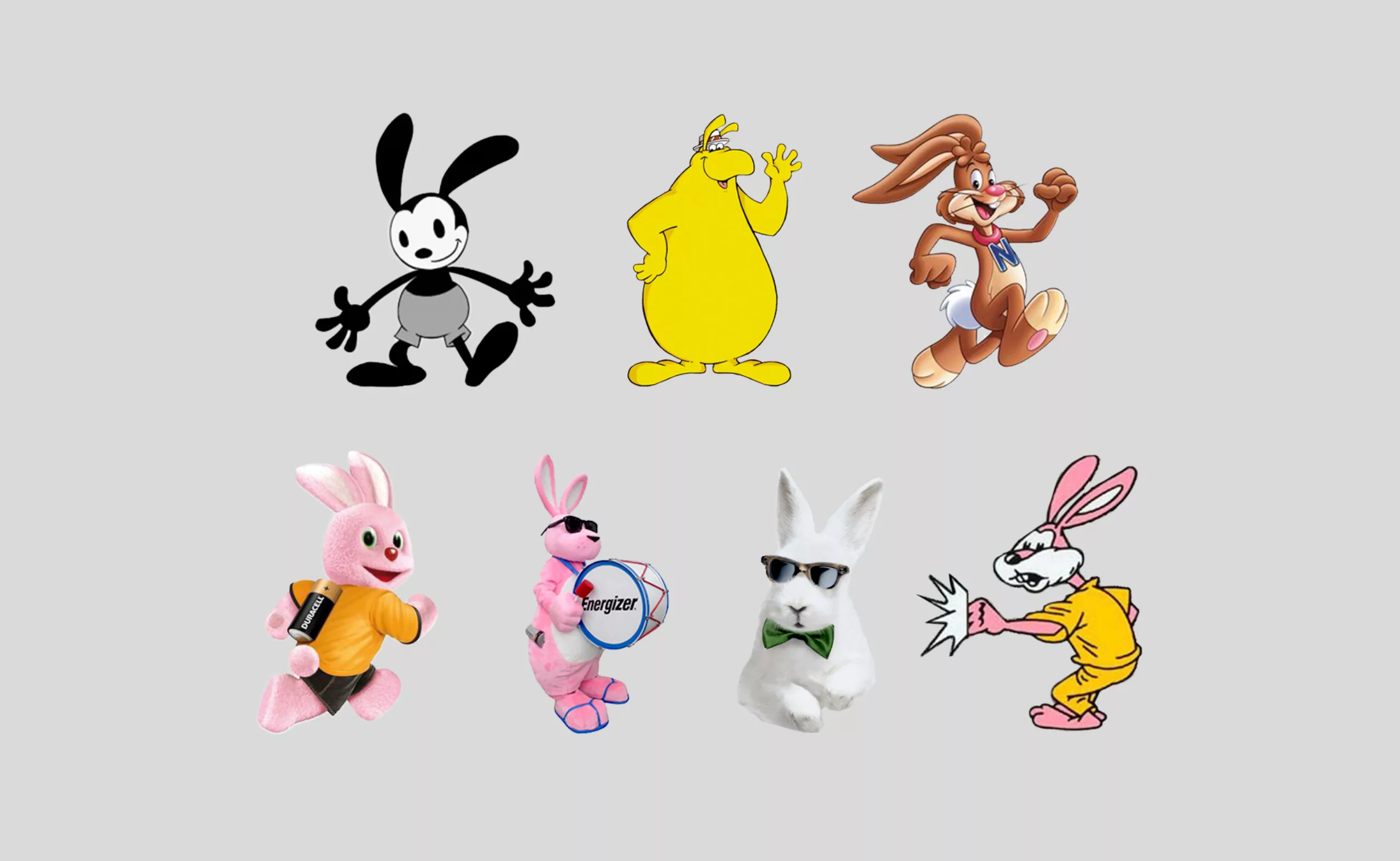

The semiotician Jean-Claude Boulay, in his article “Brands, Communication and Mascots”, describes the mascot as “an anthropological buffer that plays a facilitating role between the recipient and the sender, of which it is the displaced emanation“. It then defuses suspicion, thanks to its (more or less) reassuring features and the distance it establishes. Apart from Monty Python, who would be wary of a rabbit?

Mascots, in Search of Animation

Humanity has long tried to embody life to an inert body, and the mascot is, along with robots and avatars, one of the heirs of this long quest. Historically, this quest begins with the first human representations and the Venus sculptures of the Paleolithic, feminine talismans with exaggerated proportions, mascots of pregnant women. It continues in Greek Mythology with Pygmalion who sculpts his feminine ideal to whom Aphrodite gives life, or Hephaestus who creates two servants in gold; then in the Jewish tradition with the creature of the Golem that appears at the naming of sacred texts, or the Homunculus, in alchemy. The quest of giving motion to the inertcontinues with the automata of Alexandria in antiquity, in cultures practicing the art of masks that bring all sorts of creatures to life, is found in the animist Shinto religion that animates various “living” beings under humanoid features such as the Bunraku puppets or the karakuri ningyō automata of Japan, but also in the articulated statues in India and Egypt, then later in Da Vinci’s mechanical knight, in the Cartesian theory of the animal-machine in the 17th century, and through the numerous automata and animated mannequins that fascinated the Age of Enlightenment, ancestors of robots. More recently we find this quest on the screen in cinema, which animates the inanimate, or in modern cybernetics and robotics, which have given birth to Artificial Intelligence.

But for a long time, from Antiquity to the 13th century, non-humanoid automata were created because the monotheistic religions prohibited playing the apprentice sorcerers and giving or simulating life, a privilege of God alone. The Muslims then created magnificent clocks, and the Christians invented all sorts of animals. Because of this prohibition against animating the human form (anima means “vital breath, soul” in Latin), there was a fear that the creature would turn against its creator (as in the myth of Frankenstein). The fear that machines and robots (or AI) will take the place of humans is still very strongly rooted in the West, even today!

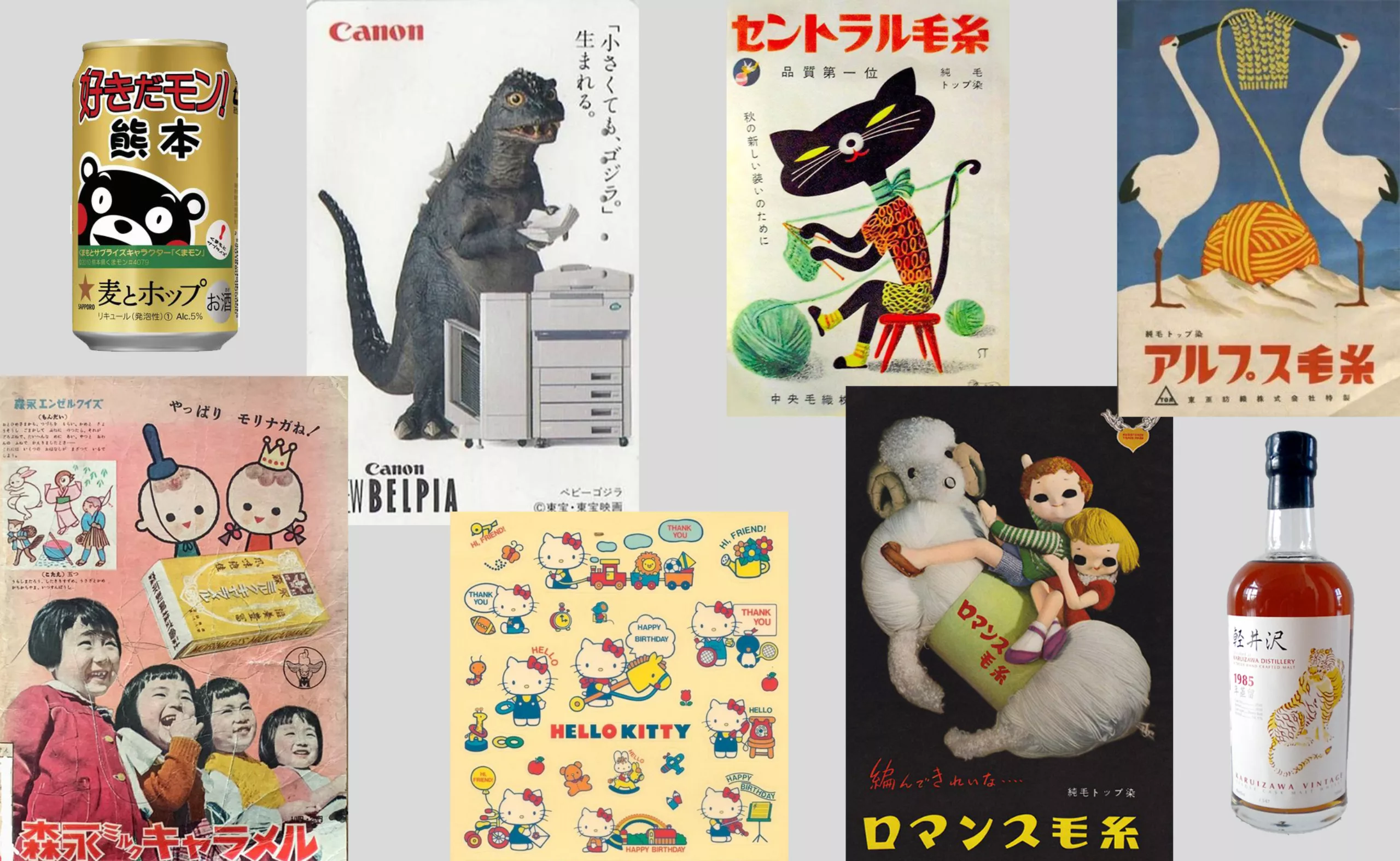

On the other hand, on the Japanese side, of Shinto belief, there is no taboo concerning the simulacrum of life. For them, matter is alive, and every thing (wood, metal, stone…) is inhabited by the kami… even if it seems inert. No movement does not mean no life. Animating a human-shaped puppet or making a radish-shaped mascot speak is therefore not strange, since the wood of the puppet is already charged with life, just like the radish. This is why mascots and humanoid robots are so popular in the Land of the Rising Sun. Before diving into the world of brand mascots, in a future article, let’s take a closer look at these kawaii mascots.

Japanese Mascots

In the wonderful world of mascots, Japan thus effortlessly rises to the top spot—not to mention that we owe the invention of Pokémon to them, which sometimes also serve as mascots. As early as the late 19th century, Japanese brands were already using animals (cats, bears, pigs…) to sell cigarettes, then textiles and alcohol from 1950 onwards. After these years, we see the appearance of 2D images aimed at a young female audience, which quickly had an effect, offering derivative products, notably “Hello Kitty” from the 1970s onwards.

In the 1990s, plush mascots were used to promote national tourism, they were called “Yuru-Kyara” a contraction of yurui masukotto kyarakutā, meaning “cute, slightly silly soft characters“. Cities, restaurants, the police, museums and even prisons or toilet disinfectant brands then adopted mascots to represent their image.

Kumamon and All His Friends

Kumamon, for example, is a very popular bear mascot of the Kumamoto prefecture, created in 2010 after the opening of a high-speed rail line, to attract travelers to the region. He was elected Mascot of the Year, traveled all over the world, and generated $1.2 billion in 2 years for Kumamoto, with $29.3 billion in 2012 from derivative products alone. If we believe what he says during interviews, Kumamon is “Commercial Director” and “Director of Happiness”and his role is to bring kindness and comfort to local populations, such as after an earthquake. A true national hero, his role is far from being taken lightly.

Bonus features: Benki Shiroishi, the guitar-wielding toilet and mascot for Sanpoll disinfectant, and Choppy, the lighthouse-cabbage from the town of Choshi.

Replacing City Logos with Mascots?

In the first image, half of the mascots represent cities and prefectures. In terms of branding, mascots play a crucial role in Japan since they complement the logos of cities or territories, which are part of a long tradition of territorial insignia. These icons are most often round, drawn and constructed around symbolic natural elements, and above all inherited from the emblems of ancient coats of arms; we are very far from the city logos of France or Europe.

The mascots of Japanese prefectures are living identities of sorts, taking up the “flagship” elements (literally, sometimes, as Choppy) of the territory – flowers, architectural elements, a local specificity – while giving them a friendly, amusing and courteous personality.

For example, the large yellow man with cap and moustache shown above is named Lerch San, Niigata Prefecture’s mascot. He embodies… a Hungarian ski instructor, Theodore Edler von Lerch, who pioneered ski teaching in Japan, enlisting in the Japanese army in 1910! The mascot pays tribute to him and promotes skiing in the region, although there is also a logo featuring the prefecture’s emblem.

Let’s play a little game: what kind of city mascots would you imagine in France? A pigeon with an Eiffel Tower hat for Paris? A bouchot-crab for Saint-Malo? A slice of cheese on skis for Arèches Beaufort? We look forward to hearing your ideas in the comments! In the meantime, here are our kawaii versions, made with MidJourney.

And in an upcoming article, we’ll be taking a look at brand and sports mascots.

Sources :

L’homme et ses signes, Adrian Frutiger

Histoire des automates, androïdes et animaux, Marielle Brie

Marques, communication et mascottes, Jean-Claude Boulay

Kumamon et le phénomène des mascottes, un monde de gentillesse