The utopia of representing futuristic cities

Inventing the future has always been a fascinating art, for both the reader and the creator, propelling the best inventions of the century and their vices to their climax. For if the future brings its share of desolations and uncertainties, linked to dry resources and sometimes badly exploited technology, the capacity of invention of the human being always remains without limit and makes it possible to create utopian ways out. In films, comic books or futuristic novels, the city and society in general are depicted under their best angle (utopia) to make men dream, or highlighting their faults to prevent a threat that would alienate its inhabitants (dystopia).

Here is an overview of the visions of some men, writers, designers, scriptwriters and architects, who contributed to the utopia of dreaming the city.

Utopia, eutopia…

It would be utopian to believe that the idea of utopia erupted one fine day in May, under the pen of an inventor, in the mind of a conquistador or into the work of an isolated artist. The notion of utopia seems intimately linked to life in society and the common desire to believe in an imaginary and idealized elsewhere. It surely appeared within a society at the dawn of its first limits, long before it took shape and was named in a book. As the psychanalist Elisabeth Roudinesco explains:

Élisabeth Roudinesco“Utopia is present in all conceptions, ideas, philosophies that want to change the world. (…) It is a distant project, but one that irrigates and nourishes hope at the heart of societies.”

The Greeks do it better

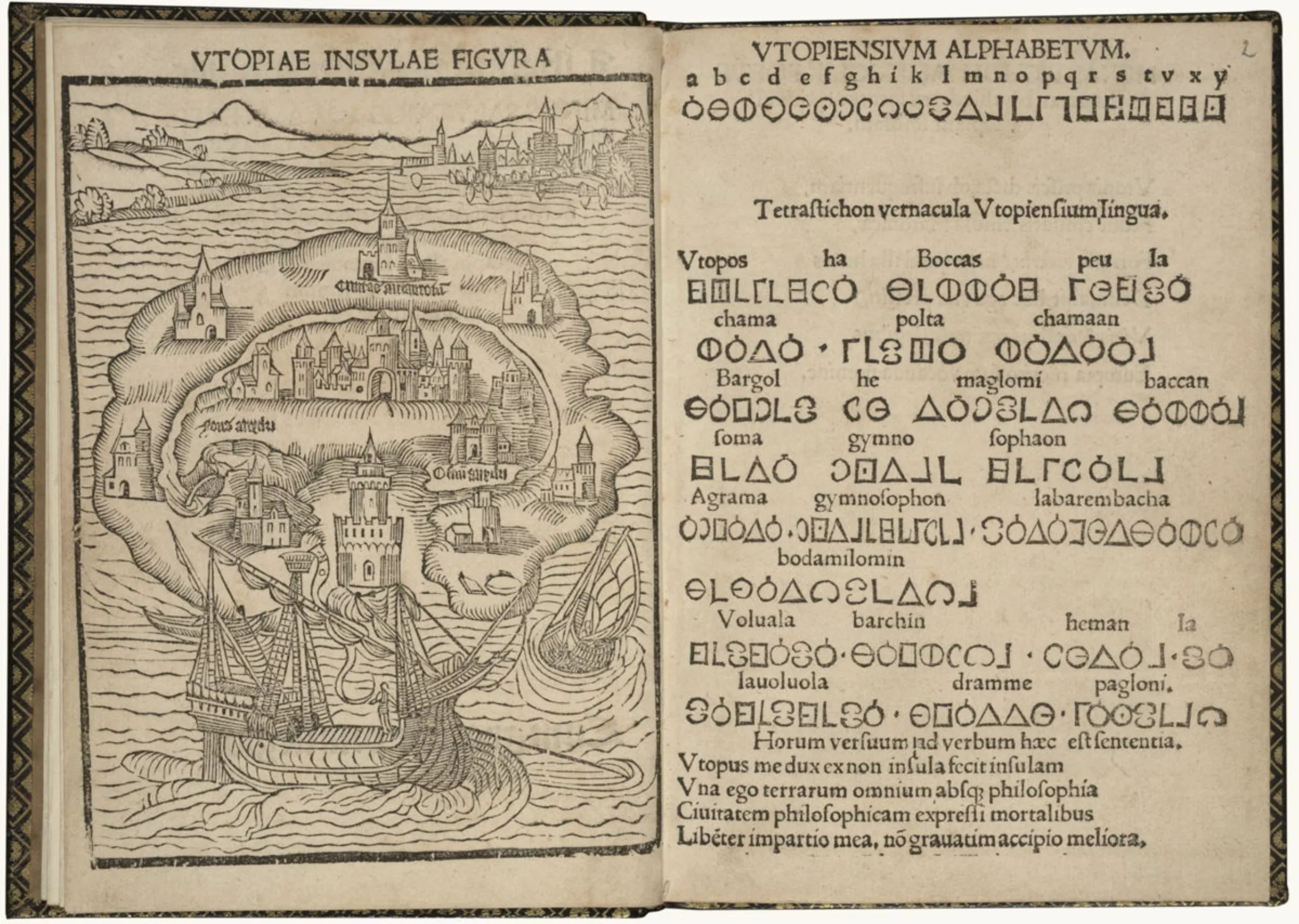

Among the Greeks, from whom the word originates, the idea of utopia is that of an ideal but past world, of an extinct myth from which one draws a certain nostalgia, a harmonious world uniting men and Gods. The word utopia is paradoxically not used among the Ancients but first appears in 1516 in the book Utopia of which we spoke above, invented by the English humanist Thomas More.

Utopia derives from the private prefix –u– added to –tópos– (place, in Greek) to describe a place that is nowhere or –eu–tópos– the place of the good.

Seeking a distant and abundant land

Indeed, utopia is both ‘u‘ and ‘eu‘: an inaccessible and unreachable place, but offering a better life. In the Middle-Age, because of the harshness of life, an ideal began to be projected in which men would be freed from evil, labour or hunger. The world being undiscovered still, the imagination had loads to create! People knew Atlantis from long ago, this engulfed island forever lost, and More depicts in Utopia a distant island in which “abundance being extreme in everything, one does not fear that someone asks beyond his need“.

As early as the 13th century, some texts mention the land of Cocagne, “an imaginary place where everything can be found in abundance and without effort, thus encouraging greed and laziness“, which Brueghel paints in 1567. We see men freed from food, in a landscape where nothing is missing and everything seems to be available by stretching out their arms, like those pancakes on the roof, or that pre-cut pig that leaps with a knife on its back juste like the boiled egg in the foreground, or that cloud of semolina in which a man dives, in the background:

In the name of Progress

Gradually, with the great nautical expeditions, the world is mapped and there are less and less room left for unexplored and idealized lands. With the advent of progress, the ideas of Enlightenment, and the impetus of the French Revolution, the motive for utopia is no longer that of a terra incognita to be discovered, but is rather part of an ideal to be attained on Earth. Around 1810, we are convinced that Progress will change the world! People have faith in man, and hope for the triumph of morality and reason. Paul Signac also signs his painting Au temps d’Harmonie with a subtitle that speak volumes: “The Golden Age is not in the past, it is in the future“.

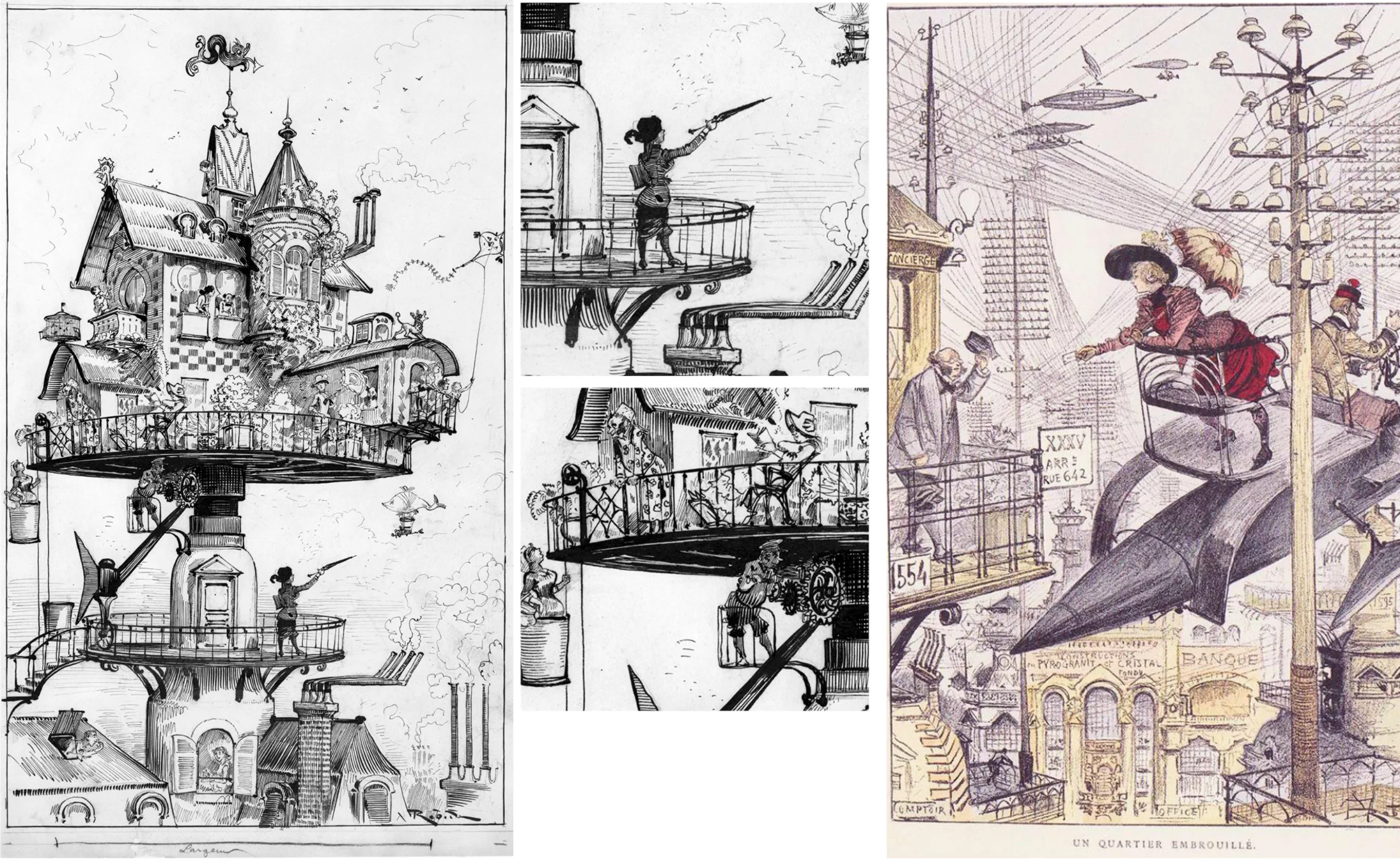

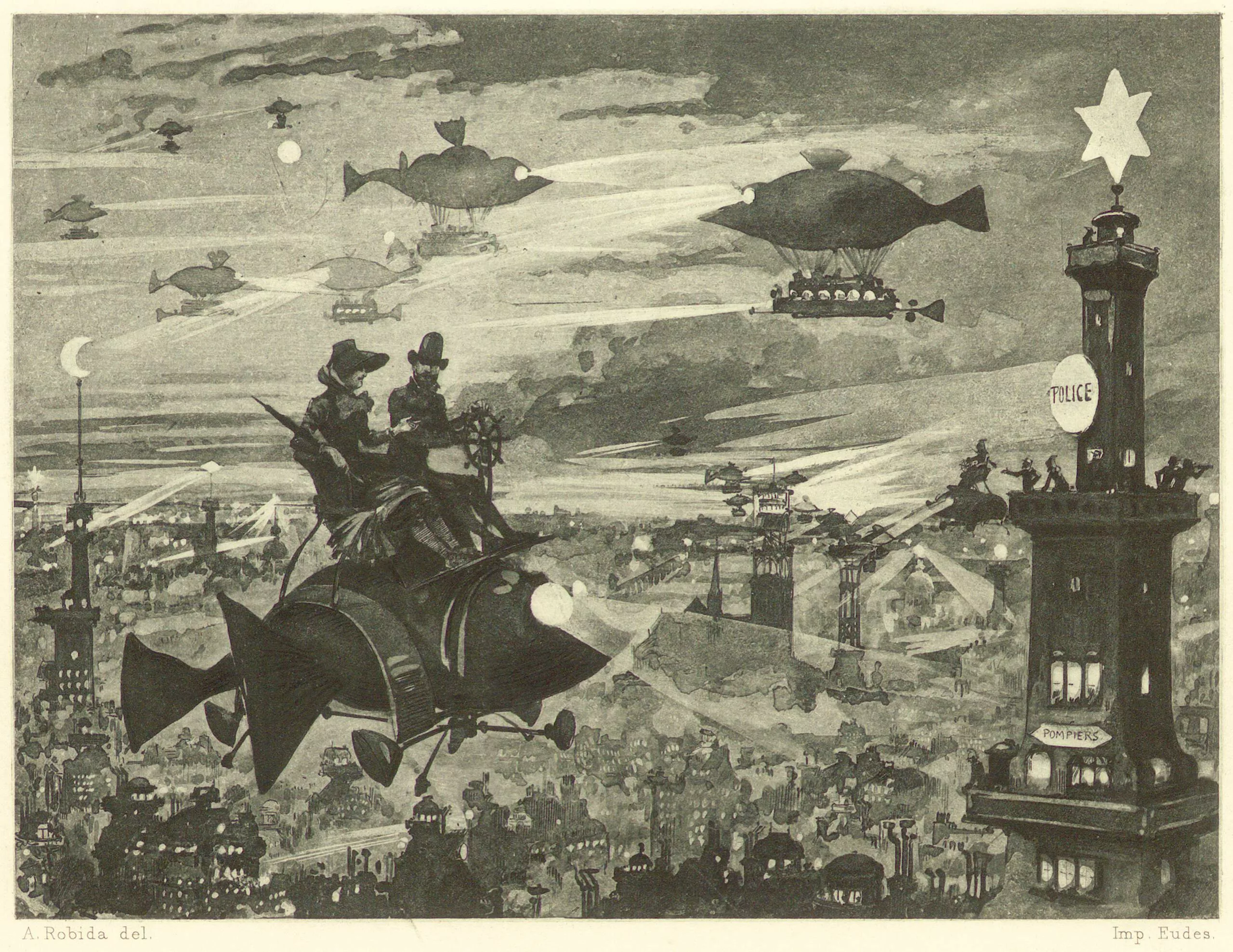

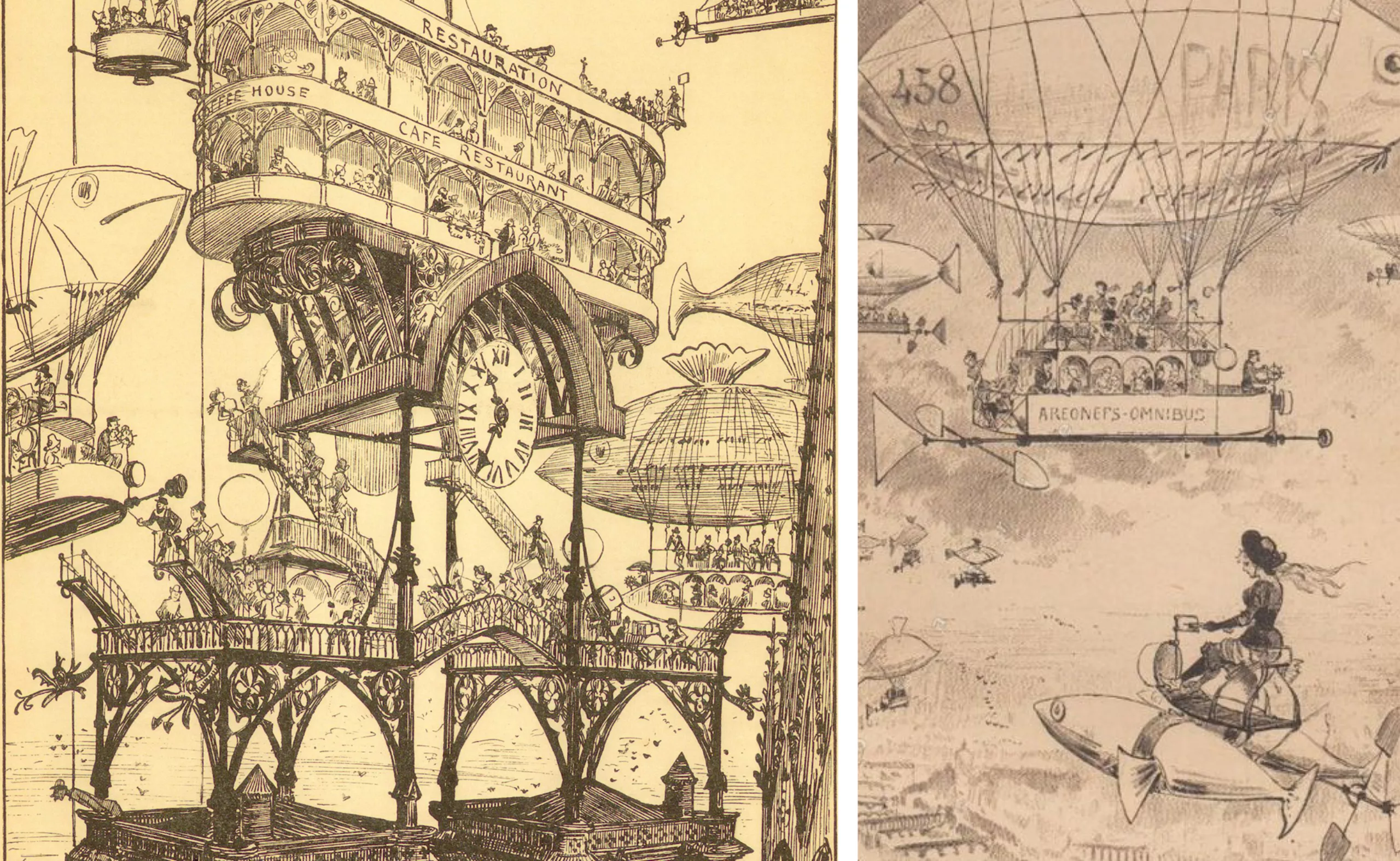

In this state of mind, illustrator and novelist Albert Robida writes a cult trilogy in which he plunges the reader into a futuristic world where the machine is the equal of man: The Twentieth Century (1883), The War in the Twentieth Century (1887) and The Twentieth Century, Electrical Life (1890).

In the first book, he envisions globalization in the Hôtel International, where “travellers rediscover, upon arrival, the lines of their national architecture and do not leave their habits, so to speak“. Robida also anticipates the feminist movements and revolts leading to women wearing trousers. He imagines a kind of Skype allowing to immerse into the atmosphere of a remote place while staying seated in your sofa, or invents the museum’s audioguide when “instantly a phonograph gives the name of the painter, the title of the painting as well as a short but substantial notice“.

Plunged by this positive momentum brought by progress, he puts inventors (and perhaps himself with them) on a pedestal and imagines an avenue with statues bearing their effigy to highlight each discovery, for even “the invention of the pot indicates the passage from the state of nature to the state of civilization“. His optimistic and futuristic vision plunges the reader of the time into a technological Paris teeming with flying vehicles, advertisements and tourists.

In his engravings taken from the first book, we see flying machines of all kinds, a restaurant floating on the roof of Notre-Dame, air traffic jams, rotating houses, or advertisements invading the slightest urban space :

The artist, by his ability to represent dreams, is a major actor of utopia. It depicts the ambitions of harmony and trust, in a fraternal impulse of general interest. By making men dream, artists promote this unconscious dream, to build a better society.

From Utopia to Dystopia

But with the evolution linked to progress are born the doubts and the possible limits of a world which one believed perfect. Utopia, if it projects the common imagination into an idealized world, intrinsically underlines the defects and vices of the present. If there is dream and projection, it is because there is a desire for change or at least a craze for something that does not yet exist.

Thomas More’s Utopia, in presenting an egalitarian and pacifist world, already decried the inequalities and vices of 16th century England. Without plunging into dystopia, which depicts a generally totalitarian society with full powers in which man is only a pawn, it would seem that there is always a worm in the fruit…

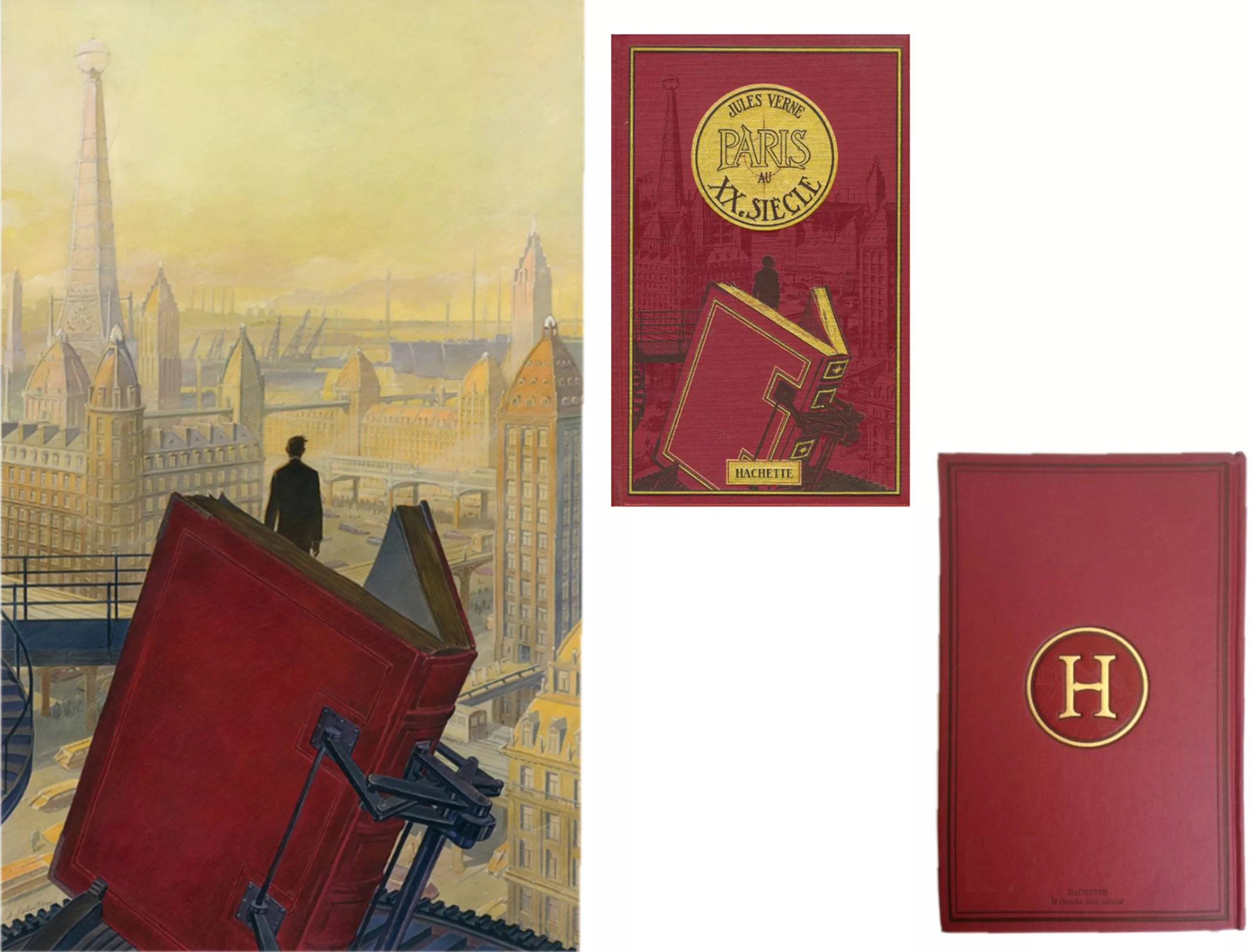

Twenty years before Robida, Jules Verne, surprisingly pessimistic, imagines Paris in the 20th century. Written in 1860, he described the capital 100 years later, in 1960, with a darker vision than Robida. It will only be published in 1994 by Hachette, his editor affirming at the time that “no one today will believe in your prophecies“. In this futuristic novel, technology and finance are the two driving principles of society, where “the important thing, indeed, is not to feed oneself, but to earn enough to feed oneself” and where art and its derivatives, judged neither useful nor productive, are abandoned.

The illustrator François Schuiten draws the images of the novel, in the style of 19th century engravings. The cover, which dates from 1995, recalls the printing techniques of vintage books. We will return below to François Schuiten’s work.

In Paris in the 20th century Jules Verne anticipated the influence of English on French, the abandonment of Greek and Latin at school, the drastic increase in motorized traffic, the rise of robotics, artificial intelligence, and the surveillance of the individual. A Paris that seems out of step with our present, but which is already alarming about certain deviances that we are experiencing today.

The failure of implementation

These “perfect” societies are often places of benevolent control, submission to a supreme (though good) law, and community life in which the individual has no place outside the group. Like many theories, the idea is good but inapplicable in practice. In the 20th century, this kind of utopia gave rise to monsters, be it Nazism, Stalin’s communism, or grandiloquent urban projects that were never really completed, or even failed like those we talked about in our article on the Paris metro map such as EPCOT or the Saline Royale.

If you want to go further, Brasilia, the cities of Le Corbusier or Auroville are one of the examples mentioned in this article on architecture doomed to failure in utopian cities.

From artist to creative: making dreams come true or selling dreams

In the 20th century, with the rise of technological advances in printing and the increasing use of photography, the artists gradually gave way to the creatives, who then took control of the dissemination of utopian messages.

Since the beginning of advertising, the codes and symbols are the same, drawn from an ancient ideal: a posture reminiscent of a master’s painting at YSL (cf this ad for the perfume Opium which recalls the odalisques or the death of Cleopatra), mythological symbols at Chanel, music with divine references in razor advertising (“I’m your Venus“)…

As in the days of painters, these advertising messages aim to encourage consumers to unconsciously tend towards a utopian model. The only difference being that instead of addressing the common good and the establishment of a fraternal society, these messages of communication encourage materialistic and individualistic consumption. The creative no longer plays the same role.

Even today, some artists encourage us to dive into the future and question our habits. This is the case of illustrator François Schuiten.

The future in comic strips

At the Étonnants Voyageurs festival in Saint-Malo, screenwriter Benoît Peeters came to tell us about his vision of futuristic cities that he mapped and invented with his fellow draftsman François Schuiten (the man who drew the cover of Verne’s book, remember), through their albums Cités Obscures, and more recently in Revoir Paris.

Peeters and Schuiten met in 1968, not on the barricades but on the school benches. One draws, the other writes. They launched a school newspaper, lost sight of each other for a few years and then got together to continue their adventure. Peeters became a Tintin specialist and comic book and storyboard theorist, Schuiten was part of the Metal Hurlant strip, the magazine founded by Les Humanoïdes Associés which brought together science fiction comics and published many of the comic strip’s leading artists.

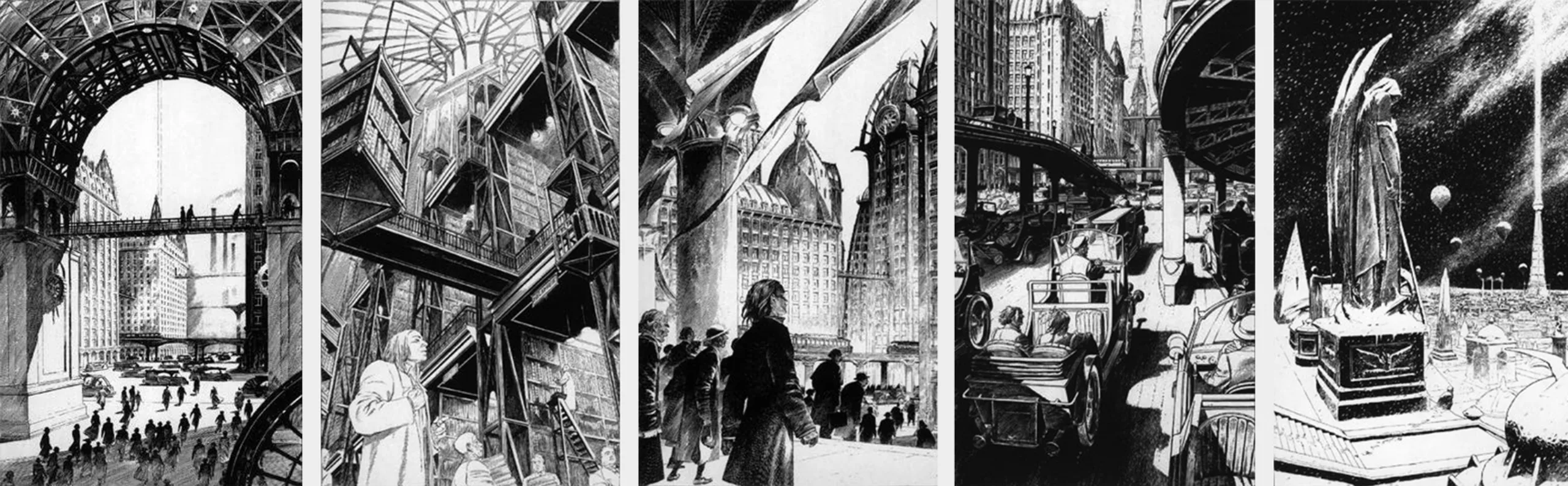

From this friendship were born the Obscure Cities in 1983, a corpus of science fiction albums set in futuristic cities invisible to humans, on a planet hidden between the Earth-Sun axis.

The cities, Brüsel, Pârhy, Urbicande or Alaxis, are based on a fantastic but coherent imagination, supported by varied characters and points of view, letting the mystery soar. Every detail is plausible, every machine is feasible. Schuiten is an architect of drawing or a draftsman-architect, and the character of cities often takes precedence over that of characters.

An alarming future

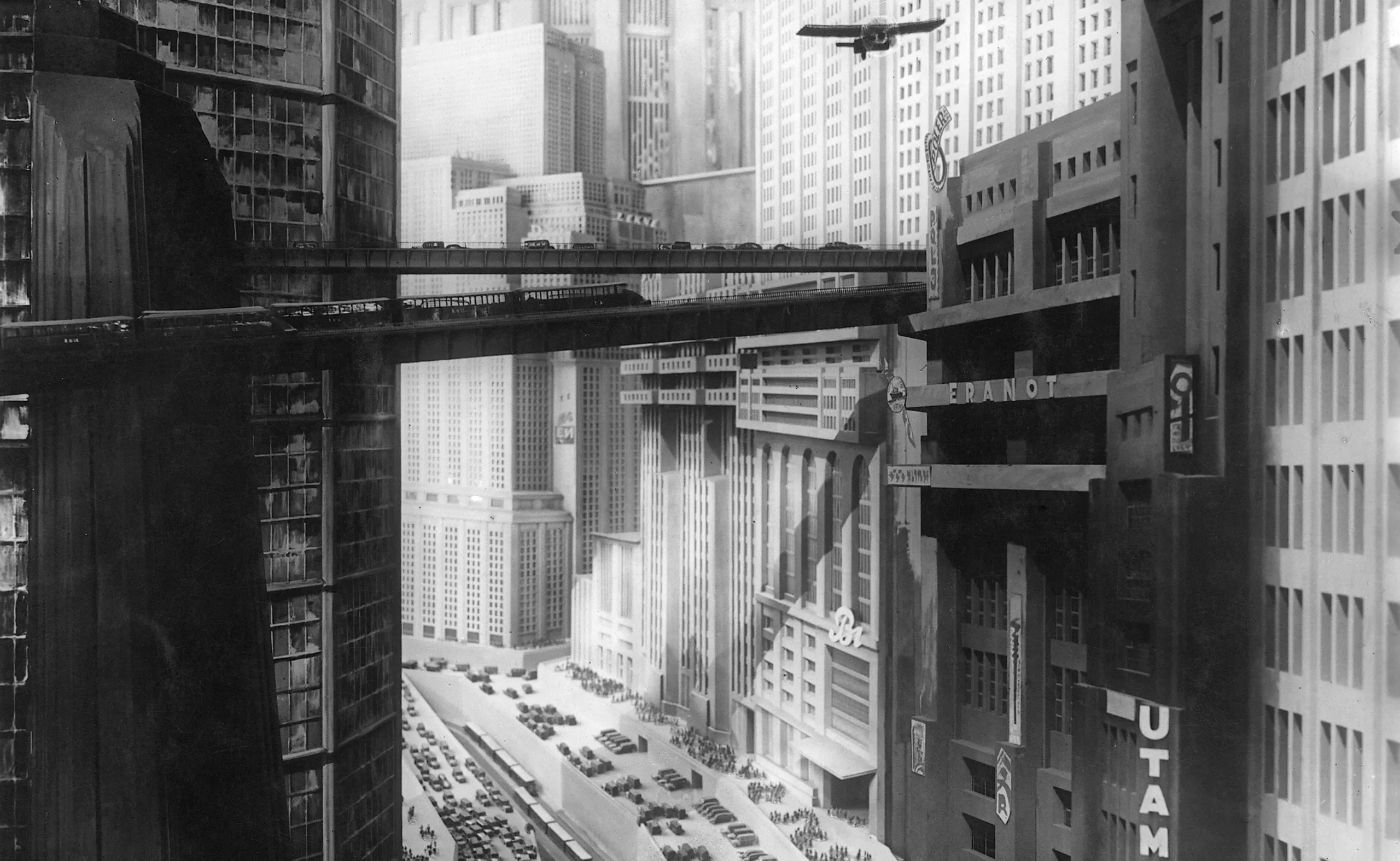

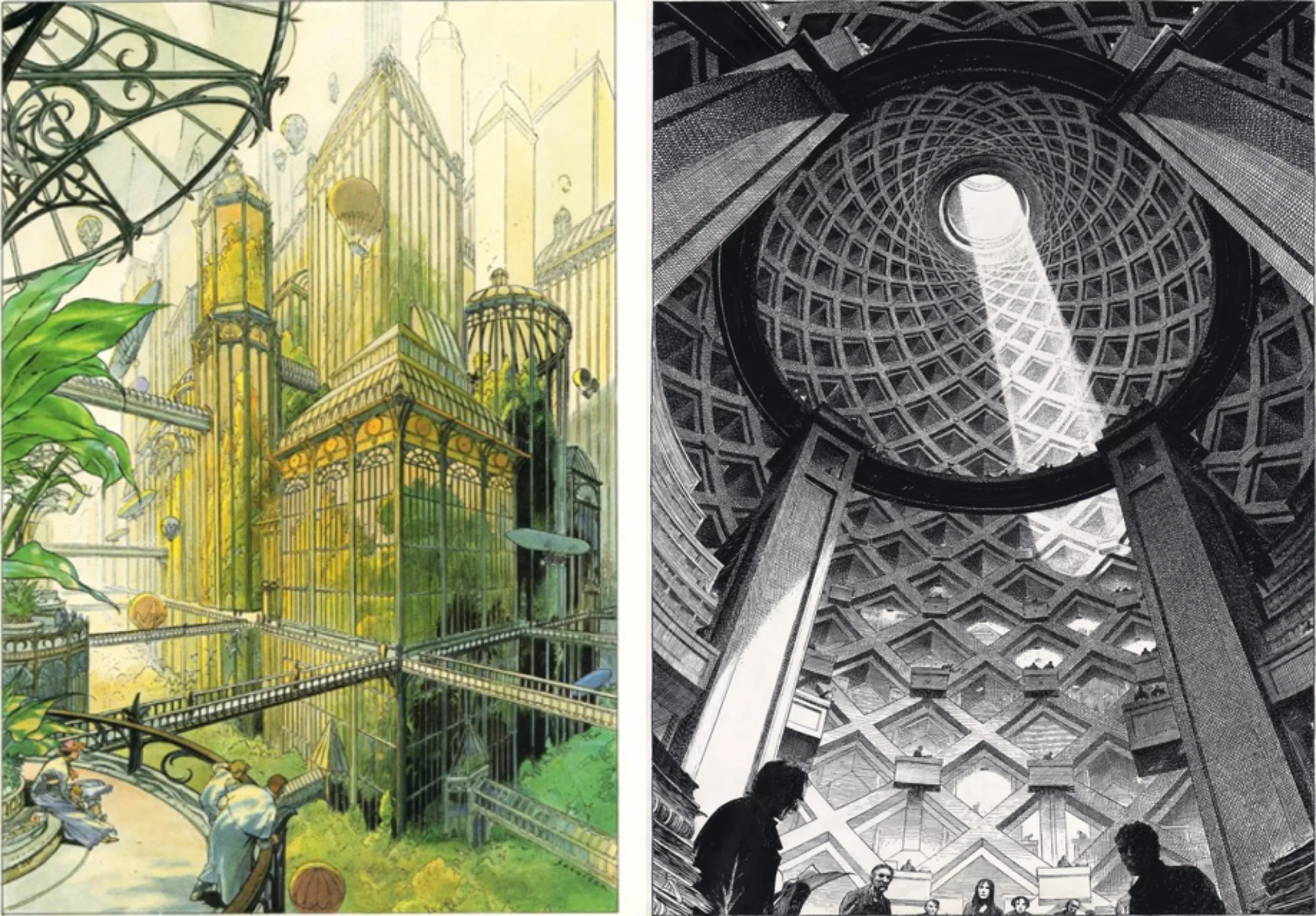

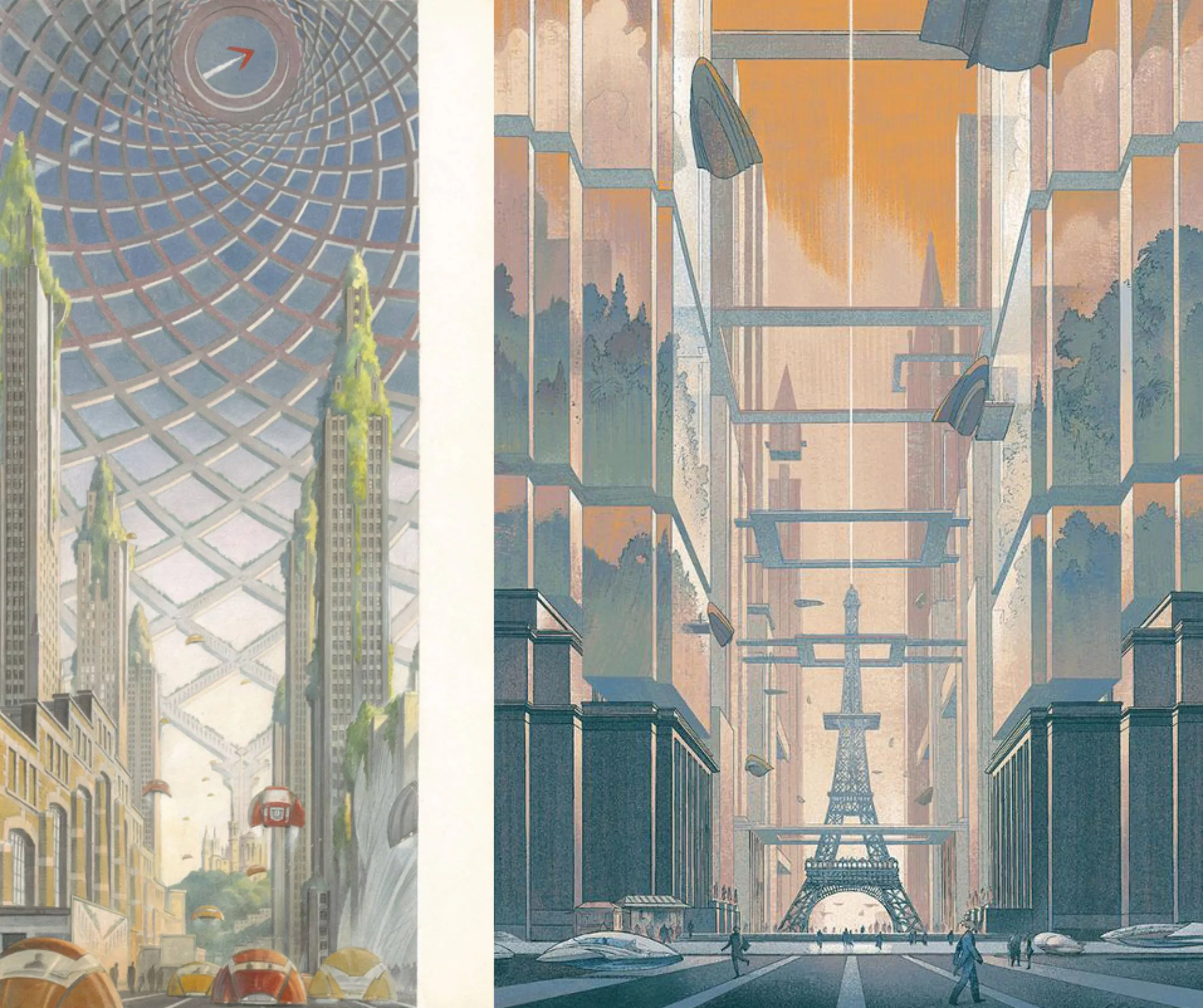

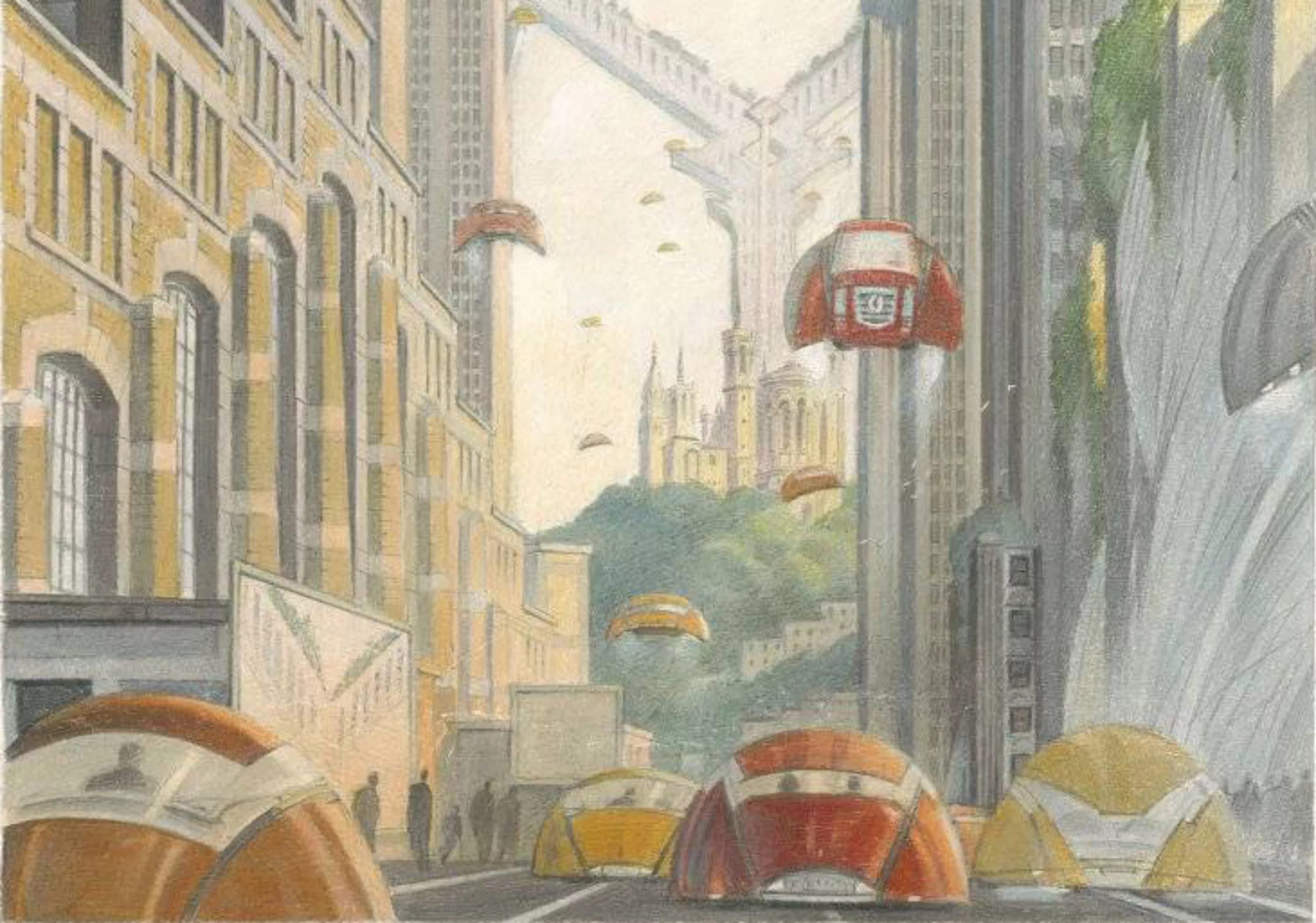

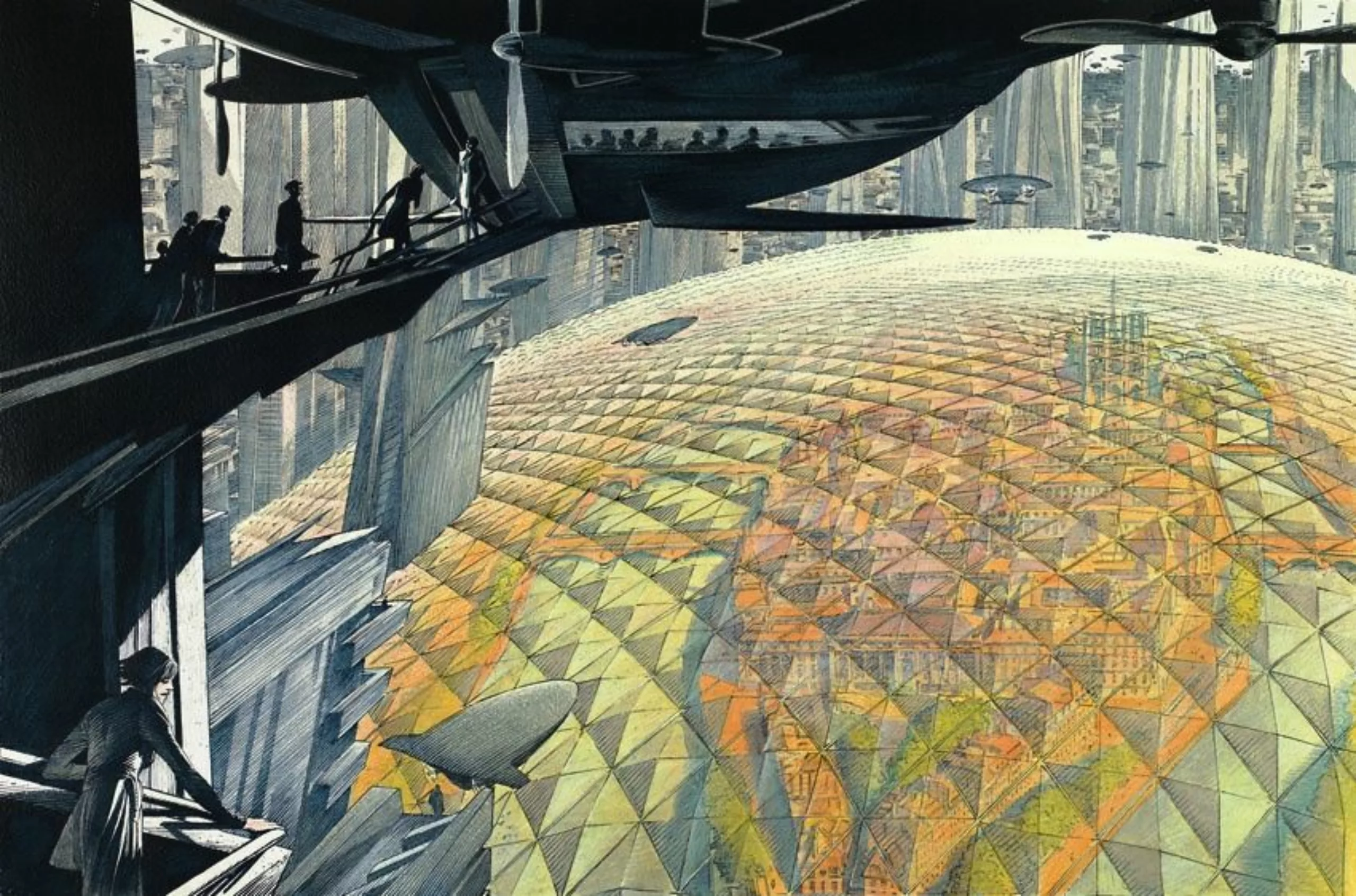

The albums talk about global warming drifting icebergs into Egypt, overabundant waste and the puzzle of recycling, becoming an extremely popular profession… They illustrate vertical cities to the extreme like Lyon (picture below, left, then the next 2 for details), or greenhouses in giant greenhouses maintained by window washers, streets covered with highways or flying machines.

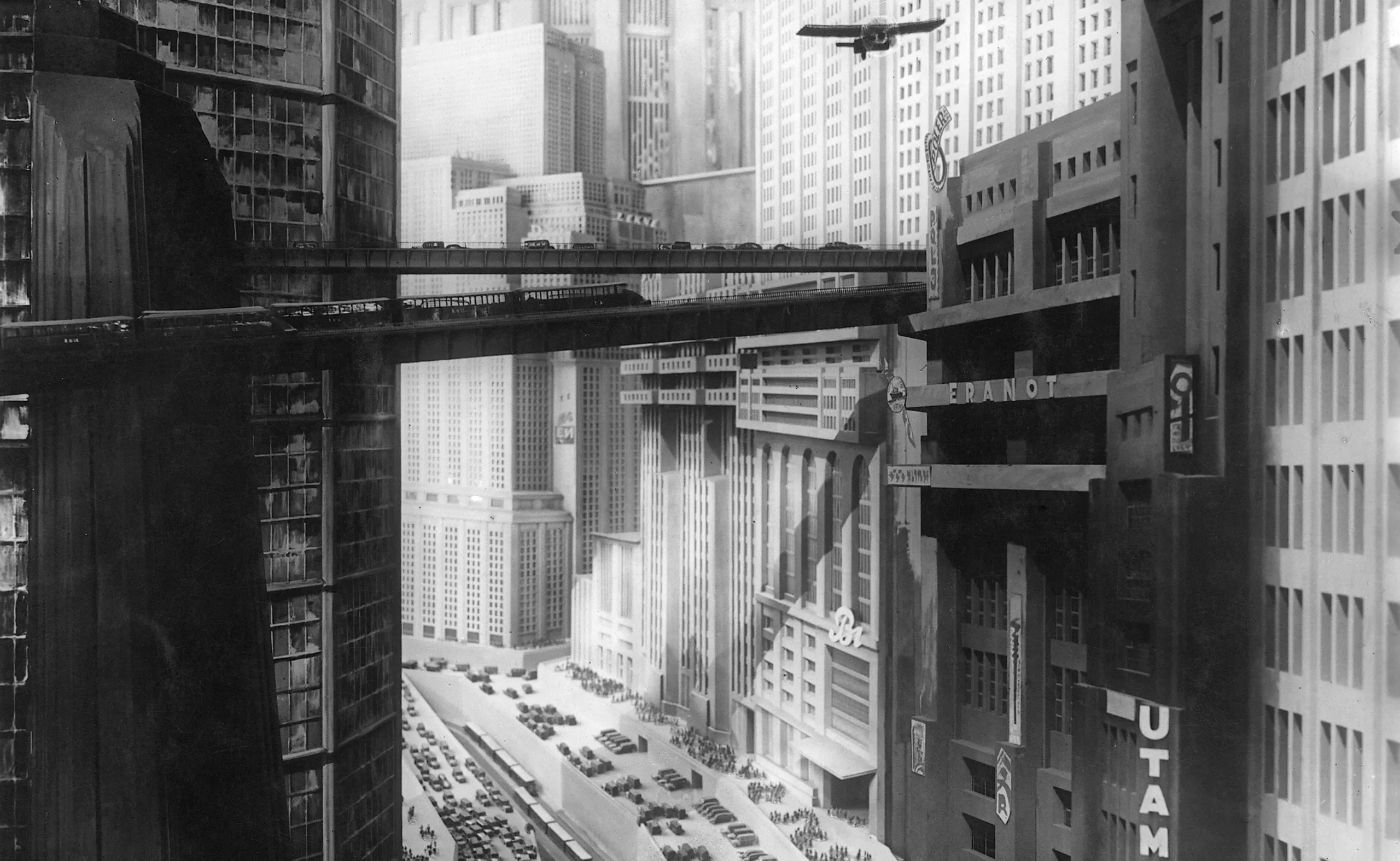

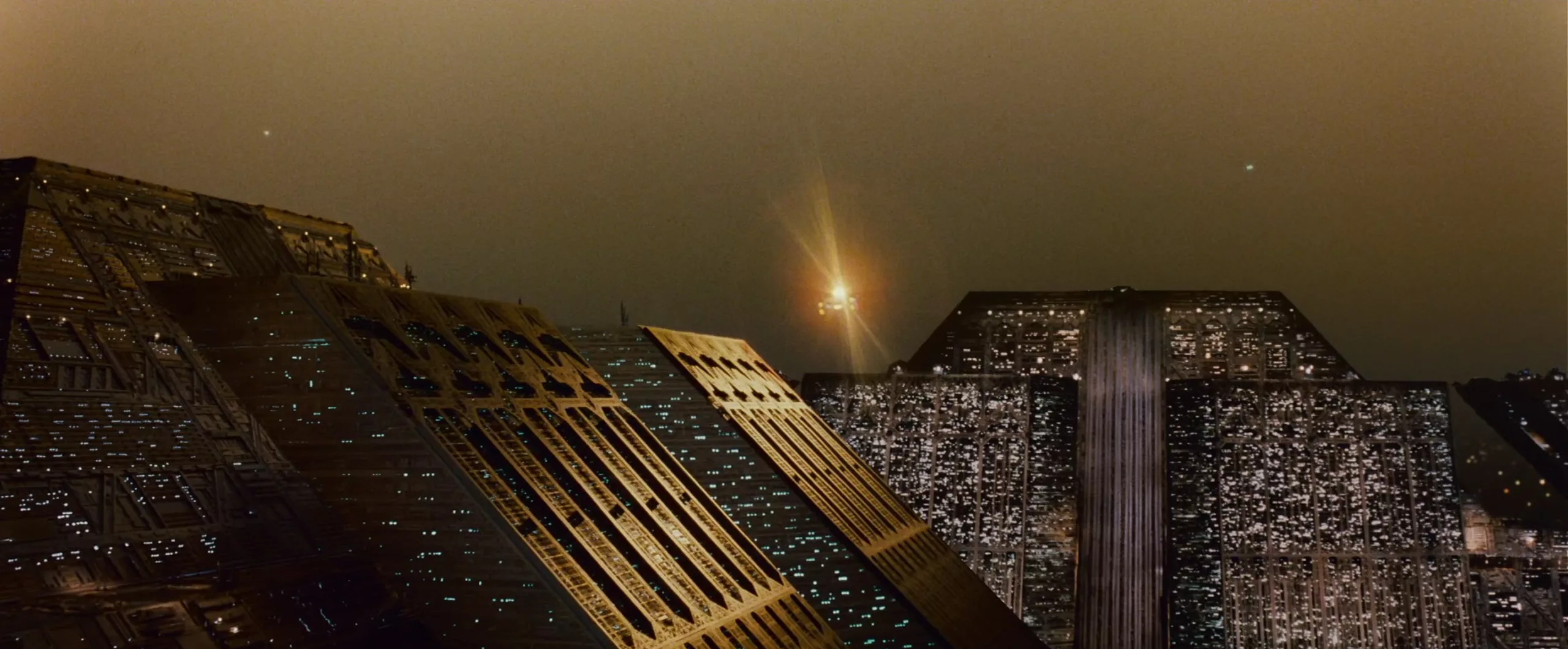

These imagined cities are inspired by books by Verne, Robina or Kafka, and great dystopic SF films like Blade Runner, Metropolis or Brazil, as illustrated below.

As Peeters explains, these worlds are neither utopias nor desired visions of the future. It would seem that they are born from a dream, a futuristic representation of the city neither ideal nor plausible, with always a worm in the apple. These are somewhat wobbly visions of the world, to make us react as a utopian vision would have done, without making us want to.

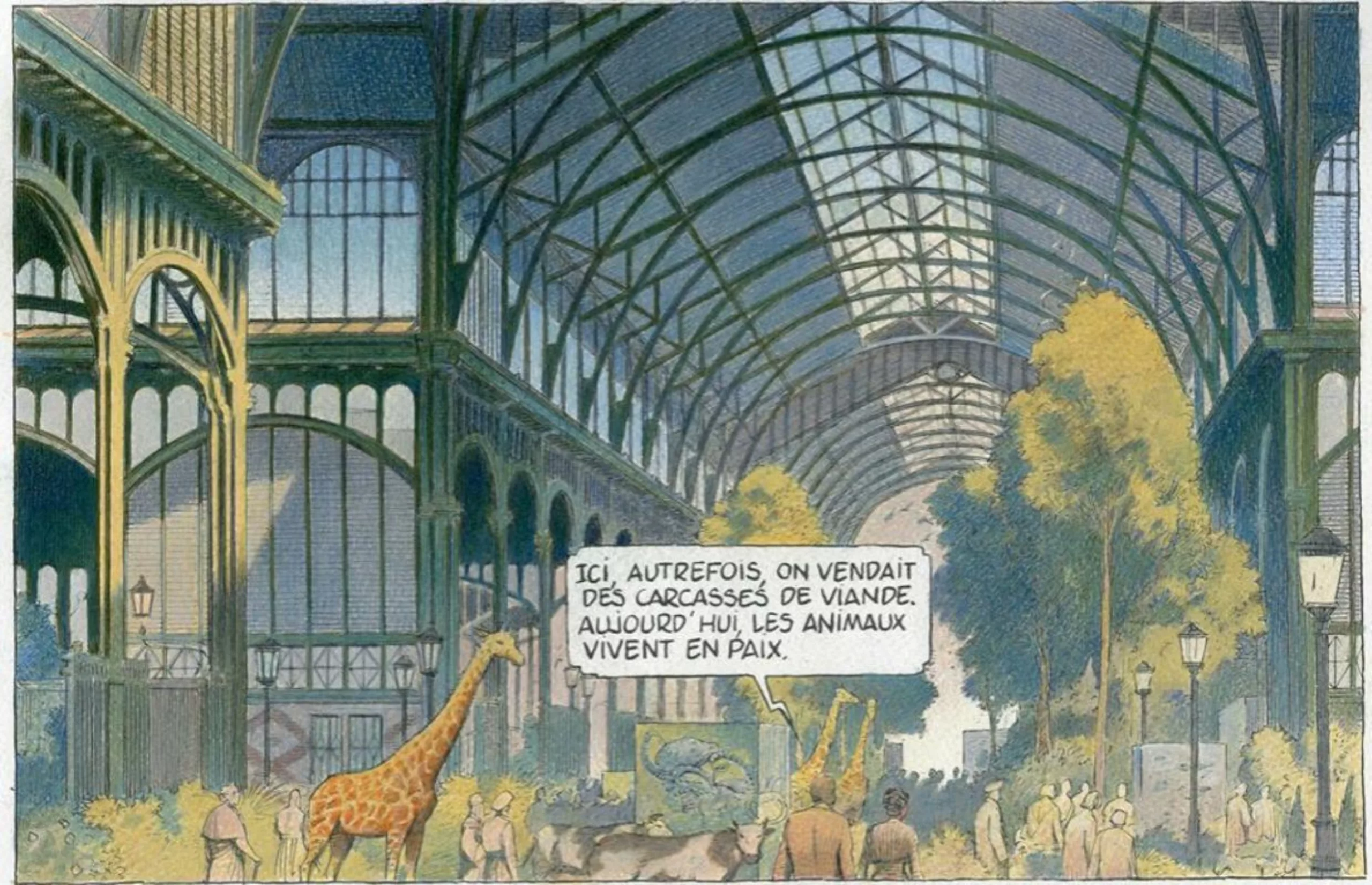

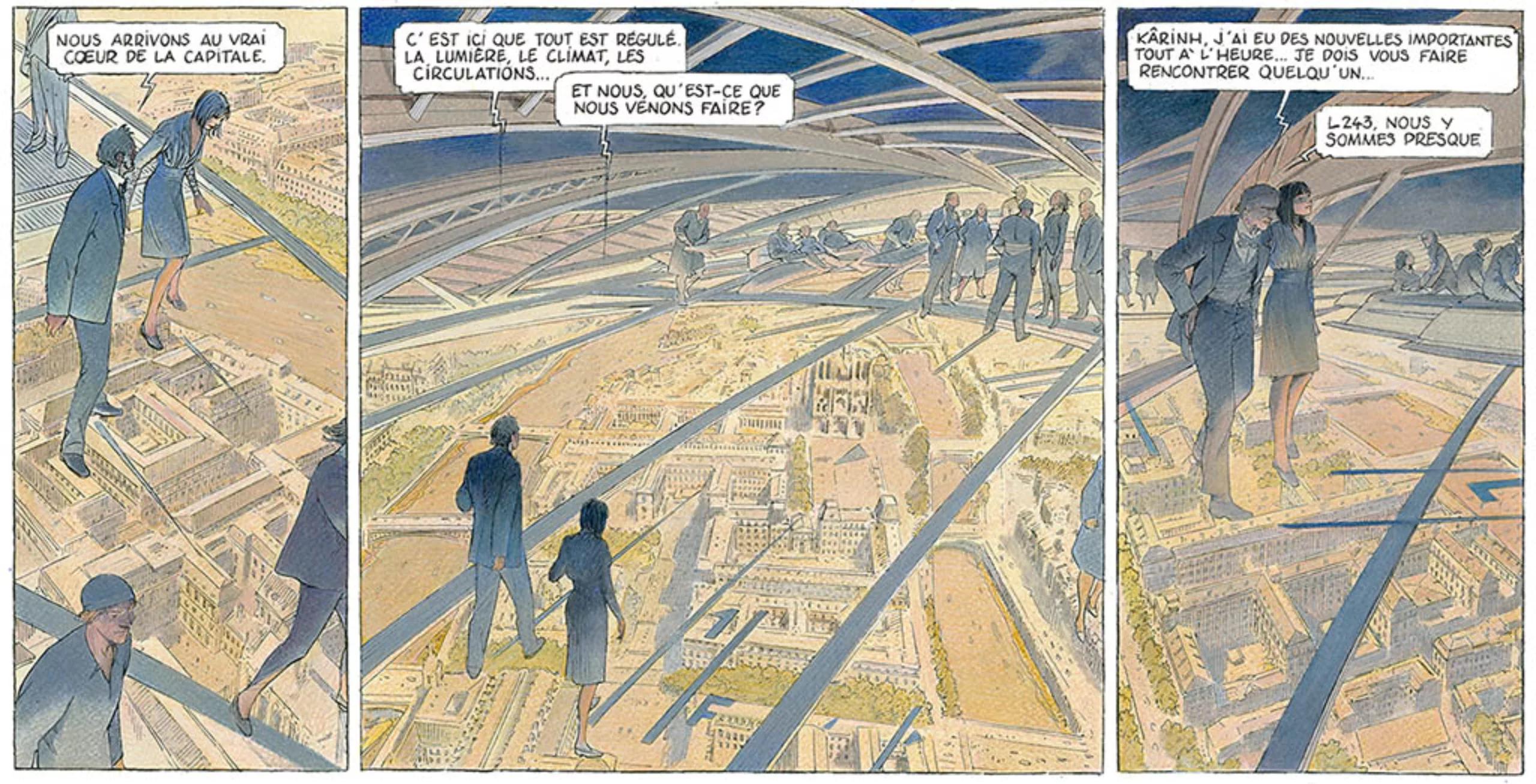

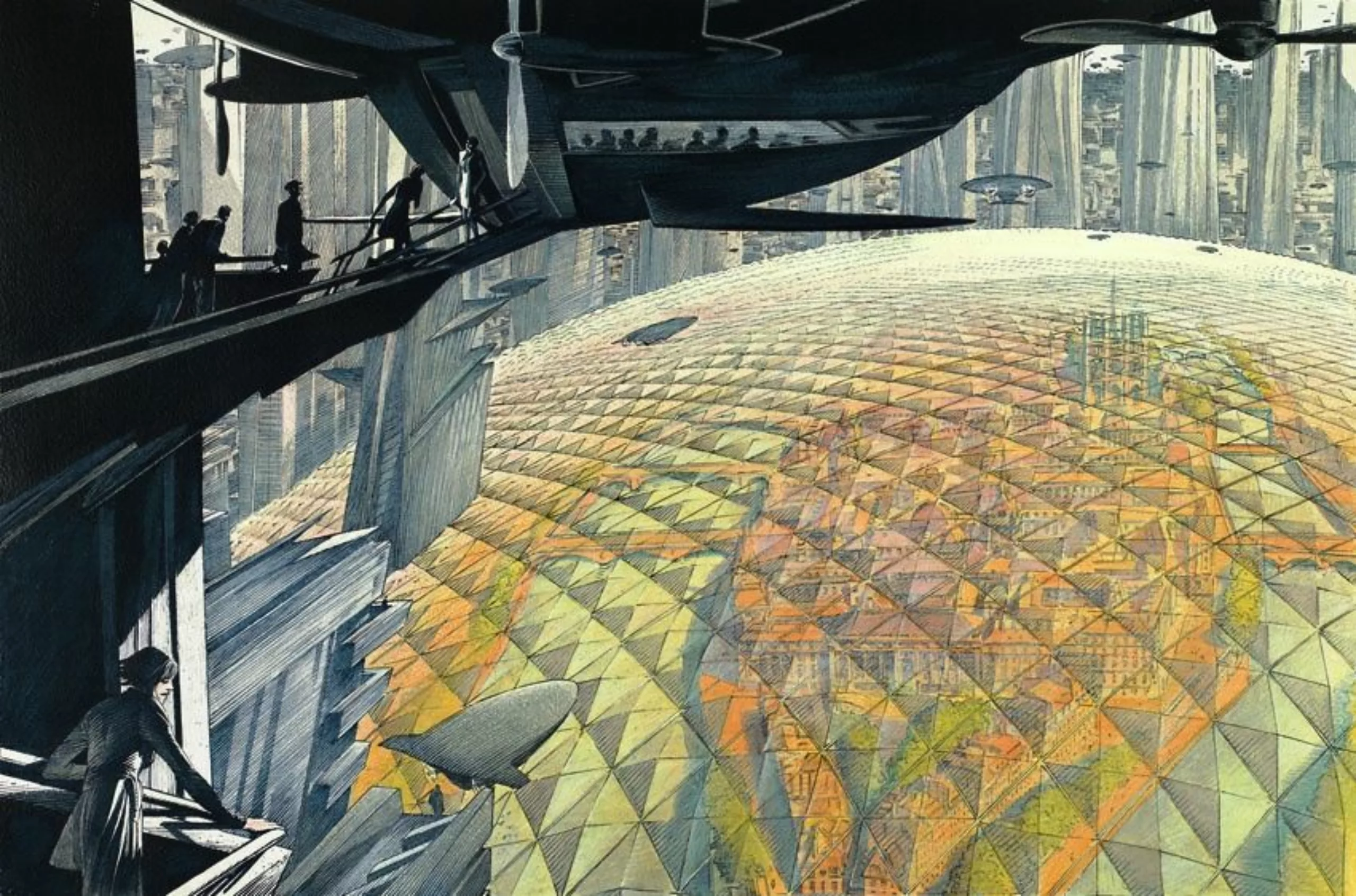

A dome on Paris

Realistic and perhaps nostalgic, Peeters and Schuiten bring the Halles back to life, rebuilt in the same way in the album Revoir Paris, which takes place in 2156. The old Paris, frozen forever in its bell where a perfect meteorology baths, makes it possible to make live with the privileged tourists a perfect experience, by strolling in buildings Haussmaniens as splendid as uninhabited, or intended for the most fortunate. Around, the black suburbs contrast with this timeless memory bubble, and echo today’s Paris. The landscapes recall some scenes from Blade Runner and Robida’s engravings, in which the man is tiny in the mad grandeur of the city. As the writer explains:

“The places we imagine are caricatures, where we put our desires and anxieties.”

The scriptwriter and the cartoonist thus underline the risk of wanting too much to make Paris a city-museum, at the risk of not being able to make it evolve with its time, and of making it a kind of giant snow globe. The role of these draftsmen and scriptwriters is therefore to alarm as much as to make you dream.

The city of the future, today

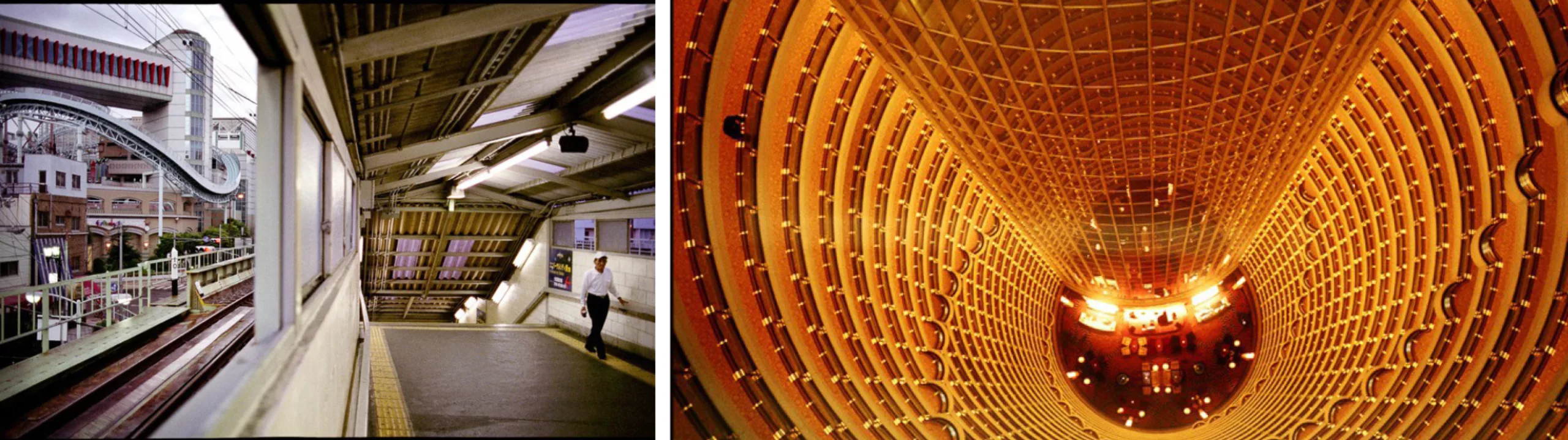

Some artists and architects already live in the future, and imagine the real cities of tomorrow. Others, such as the photographer and architect Cyrus Cornut, do not imagine but show cities in which “the human scale is reduced to nothing. Man with an individualistic future gets lost in the urban ocean. Houses fall, skyscrapers grow.” A brutal and disturbing vision of a very realistic present.

With his architect’s eye he composes images that look like futuristic comic strips, like here in Asia, where concrete lines draw dehumanized landscapes :

Showing reality, these photographs give us food for thought about our future, and question the place of man in the city.

Among the architects who imagine the city of tomorrow, some create utopian projects straight out of a science fiction film, in counterpoint with the choke cities photographed by Cornut. Futuristic but real representations.

Green city and jewel city, the eu-topies of the present?

Imagine a green city in the middle of the desert. This is how the city of Masdar, in the United Arab Emirates, stands, an ecological “source” (masdar in Arabic) built since 2008 a few minutes from Abu Dhabi airport.

The houses, inspired by the traditional local architecture, are next to the business buildings. All the buildings are passive so do not consume energy and offer a natural air conditioning with 10°C less than outside. The key word of this success: technological and ecological progress. A large field of solar panels supplies the city, entirely pedestrian, and crossed by a network of automated electric vehicles.

Masdar, which already welcomes several thousand people, wishes to attract international companies: no taxes, an installation in 5 days, an incubator and an ecological research & development centre. Are you looking for a new office…?

Above all, we must ask ourselves whether this kind of model, which forces nature to flourish in the desert, is really sustainable or rather chimeric? One would more willingly bet on a city like Tafilatet in Algeria, an oasis that promotes permaculture in nature and society, and seems destined to a greener and more sustainable future.

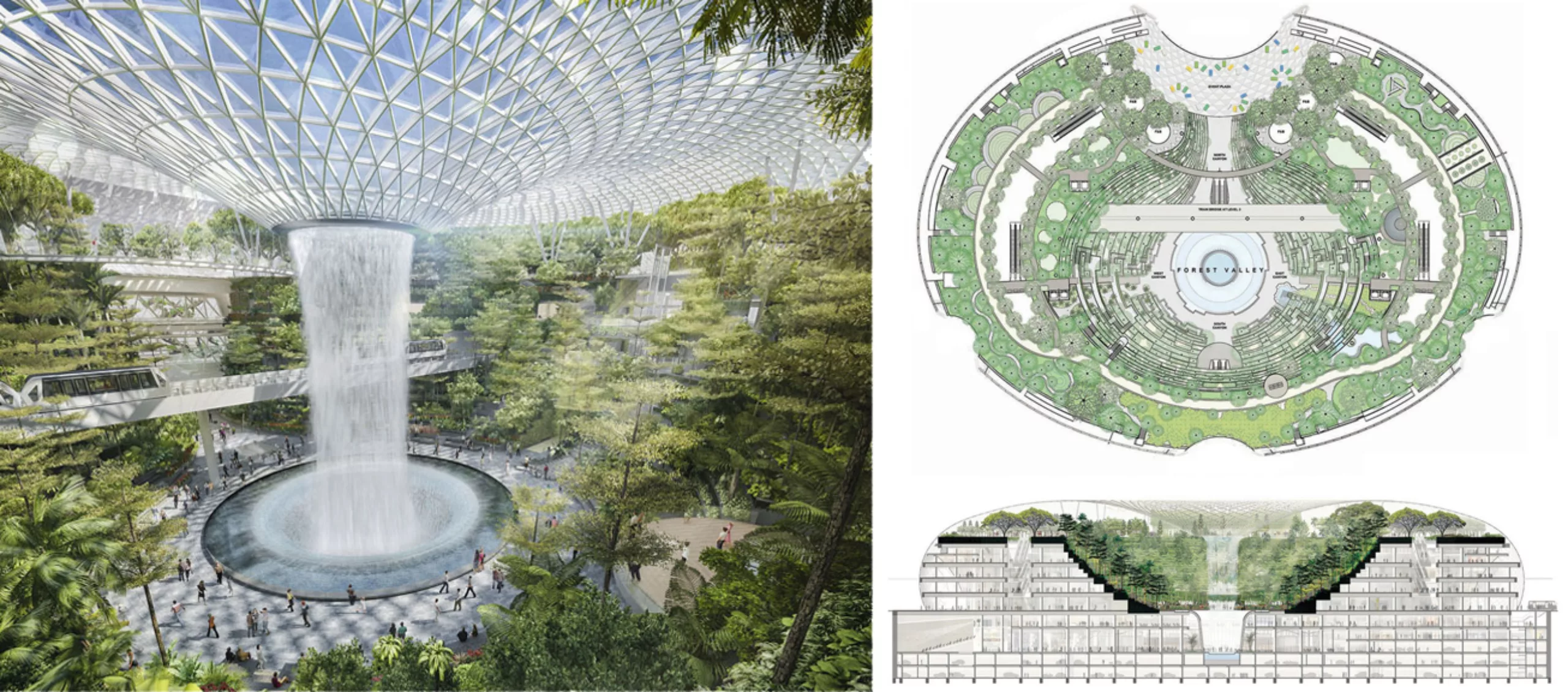

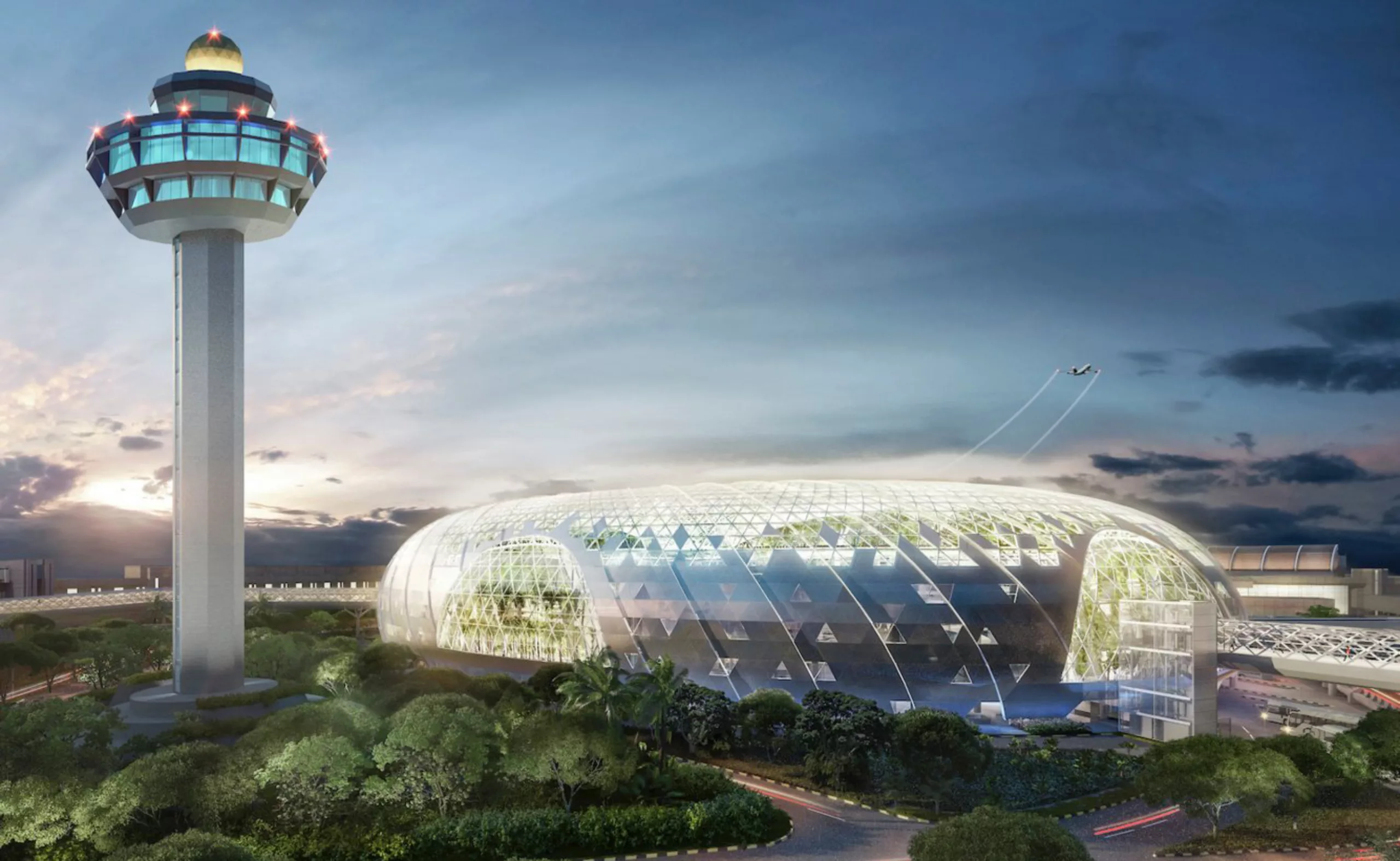

We could write for hours about futuristic projects that will soon see the light of day, especially in Asian megalopolises. One of the most surprising architectural projects of the moment is the realization of the “jewel” of Singapore airport, scheduled for 2019.

The structure of the Jewel of Changi combines shopping centre, suspended canopy, restaurant, hotel and gardens, around the “largest indoor waterfall” (Singaporeans love doing the greatest things in the world). Not to mention the airport function, of course. A kind of mini-city in the city, where you can have fun, eat, consume, sleep and travel.

This kind of futuristic structure impresses by its eccentricity and its grandiloquence but seems to have no other function than to be a eu-topie, a “place of the good”, in which everyone would come to have fun and stroll. This construction is destined to become a fictitious and concentrated place of comfort, just like Singapore, a city of consumption and entertainment. A bit like Paris under its dome imagined by Schuiten and Peeters, the Jewel will be reserved only for the richest, under an ideal temperature, far from the worries of everyday life. Like a representation of the city, idealized but unreal.

As a reminder, the Schuiten dome under which an ideal Paris sleeps:

As we have seen, the utopian city projects of the past have been doomed to failure, overtaken by socio-demographic questions. Would the key to success in a utopian city today be to design it on a small scale and reserve it exclusively for elites (as in Singapore) and investors (in Masdar)? Perhaps, by definition, the u-topic city must remain a “place of nowhere” and continue to exist in the imagination of men…?

To go further:

- Villes et utopie : l’échec

- Le 1 : voyage en utopies

- La ville de Masdar