Heineken saves its star

Viktor Orbán is crying foul!

Nothing is going well between Hungary and the Heineken beer brand. It wasn't exactly true love since the beginning of the affair pitting Heineken and its Ciuc brand, distributed in Hungary, against the Magyar brewery Csiki (a question of translation which we explain a little further down) sold in Romania and very popular with Hungarian expatriates (who represent 6% of the Romanian population), but now it's become outright war.

The Hungarian parliament is preparing to pass a law banning the commercial use of totalitarian symbols. From the swastika to the hammer and sickle, including, of course, the red star, symbol of communism.

While, on the whole, the existence of such a bill is understandable, particularly in a country that was a victim of the Nazi and Bolshevik regimes, the reasons behind it are much more base than they appear, and are aimed directly at the Heineken brand. Indeed, Viktor Orbán, the Hungarian President, is a rather chauvinistic and protectionist (diplomatic euphemisms, not to say racist and nationalist). Obviously, you can add "vindictive" to his list of qualities. Already the subject of controversy over certain laws specifically aimed at foreign companies, this text on symbols would particularly target the Dutch brewer in retaliation for the Ciuc vs Csíki case. Come on, because you're kind, we explain everything to you so that you can fully understand the ins and outs of this saga.

A great Dutch against a small Romanian

Here's a look back at the case behind the bill. In 2014, a Hungarian brewery located in Sânsimion, Transylvania, Romania, released a lager called Igazi Csíki Sör. Transylvania may be in Romania, but it's a region mainly populated by expatriate or historic Hungarians. Hence the strong Hungarian culture.

Romania as a whole is a beer-loving country, with just under twenty breweries whose products are distributed throughout most of the country. Four of these belong to the Heineken group, which accounts for almost 30% of the country's beer market, and markets a blond beer called Ciuc Premium. So on the shelves you'll find Ciuc and Csíki. Problem: the word Csíki in Hungarian translates into Ciuc in Romanian. For the record, it's the historical name of a corner of the Carpathian Mountains in the days of the Kingdom of Hungary, a corner that has been in Romania since 1918 (go back to your history lessons, dammit!).

Csiki and Ciuc are in a boat

So, in short, Ciuc and Csíki found themselves side by side in the stores. Except, of course, the Heineken group didn't like this, and decided to take the Lixid Project brewery, which produces Csíki, to court to have it banned from sale altogether, on the grounds that its name was too reminiscent of Ciuc and could mislead consumers. An initial ruling dismissed Heineken's case, followed by an appeal which was also unsuccessful, and a ruling in favor of the defendant. And so Csíki quietly continued production and distribution. As expected, when you're worth nearly 20 billion euros, you don't take it lying down!

Heineken appealed to OHIM, the European Union's intellectual property office, good lobbyists that they are, for trademark counterfeiting.

A boycott was launched in Romania and Hungary, calling on beer lovers to stop buying the Dutch giant's brands.

January 2017, boom , OHIM, now EUIPO, finally vindicates Heineken and orders the Romanian justice system to do its job, i.e. the small Lixid Project brewery now has 30 days to ban Csíki products and destroy all production and related items. End of story, Goliath has taken down poor little David.

Budapest sees (the star) red

The Hungarian government got involved, and President Orbán - who, as mentioned above, doesn't like his citizens being attacked - proposed a law banning all signs that might remind people of the country's various dictatorships. Aimed directly at Heineken, this proposal (which wouldn't have much chance of succeeding as a law in any case, as we'll see later) began to cause a stir, and put the spotlight on the Ciuc vs Csíki affair among Hungarians. Protests erupted, and in February, resigned but still there, the brewery released Igazi Sör, the same beer, with the same recipe, the same label, but a different name. We manage to recover from this legal setback and even launch the beer under yet another name in Hungary, since we've made quite a few friends there with this case.

But the story isn't over: on March 27, 2017, Lixid Project announced on its Facebook page that peaceful discussions were underway with Heineken Romania to finally bring the two beers to life in harmony.

And the next day, the same Facebook page officially announced that the hatchet had been buried:

"HEINEKEN Romania and Lixid Project SRL will settle their ongoing dispute.

HEINEKEN Romania and S.C. Lixid Project SRL are pleased to announce that after constructive discussions, the two brands intend to settle their dispute over the name Csiki Sor.

In the agreements, HEINEKEN Romania gives its consent to Lixid Project SRL to the coexistence of the Ciuc and Csiki brands, and grants Lixid Project SRL the right to market Csiki Sör beer. In return, both parties will drop all lawsuits and legal actions relating to this commercial dispute.

The agreement includes compromises on both sides, and allows both companies to continue building relationships with their consumers, employees, business partners and the local community. Both companies are now focused on putting their differences behind them and concentrating on what we do best and what we prefer to do: brew beer. "

A neutral star

Without daring to admit it, for Heineken this agreement was made mainly to appease the Hungarian government, because yes, it's all about the logo. Heineken has no plans to part with its red star, which has absolutely no political connotations whatsoever.

Indeed, the red star had been used by the brand since the early 1930s, long before the symbol became that of communism in the aftermath of the Second World War. If we follow the chronology of this symbol at Heineken, the star was used right from the start of the brand, in 1883 (at least), just as a black outline. It became red following a trial of a rectangular label for the Dutch market in the early 1930s. This red star remained on the brand's labels until 1951, when the symbol was appropriated by the Communist regime. To counter this, Heineken decided to lighten the star, keeping only the outline red, so that no link could be made between the brand and politics.

It wasn't until 1991, with the collapse of the Communist bloc, that the brand put its full red star back on its label.

Today, the Red Star is still worn by some communist countries, such as Cuba and China. But Heineken refuses to see its star associated with communism.

But why a star, anyway?

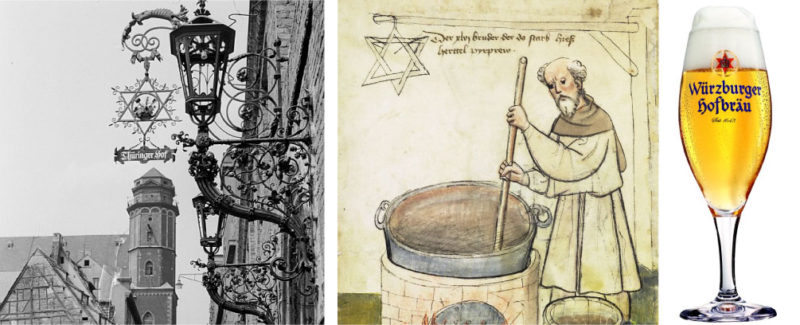

Red, green, khaki or with pink polka dots, the star is a recurring symbol in the world of beer: to understand this, we need to go back at least to the 14th century, when the six-pointed star was the sign of the brewers, an alchemical symbol representing the elements and stages involved in making a good beer and protecting the brewers. This star, similar to the Star of David but with no connection to Judaism, still adorns some beer logos and brewery signs, particularly in Alsace. Use of this symbol began to decline at the end of the 18th century, probably after the Congress of Basel in 1897, which formalized the six-pointed star as a symbol of Judaism. Many brewers then adapted their star by reducing it to 5 branches, so as not to be associated with religion.

Before the war, for example, Kronenbourg's Tigre Bock featured this star on its coasters.

Whether 4, 5, 6, 8 or 10-pointed, the star is one of the most complex symbols in the world of semiology, and is widely used in the world of brands and logos. The Heineken case is an opportunity for us to prepare a forthcoming article on the use of this symbol in logos.

Moral of the story

Over and above the legal dispute, which is obviously ending well for everyone, with both breweries aspiring to live in harmony in the best of all worlds (that of beer), what is striking in this whole story is the pressure (not the kind you drink) that the Hungarian government was able to put on the Dutch group. Threatening a brand with the banning of its seemingly innocuous logo is censorship at the highest level of government.

And Heineken would not have been the only one concerned. The head of the parliamentary group of the Hungarian president's party, Lajos Kosa, acknowledged that the bill needed to be refined so as not to penalize "brands that use the Red Star, but not as a totalitarian symbol", citing San Pellegrino mineral water in particular, which is also distributed in Hungary. A double discourse that fails to take into account the beer brand's history.

Soccer clubs (Red Star FC, Red Star Belgrade, to name but a few), San Pellegrino, Converse, Macy's (although Macy's in Hungary is a long way off) - these are just some of the brands that would be penalized by this measure, all to spite a binouze that's a little too arrogant.

Although the legal action between Heineken and Lixid Project is apparently over, the draft law is still being worked on in the corridors of Budapest. To be continued. In the meantime, it's thirst-quenching, but in moderation.

Source : Collection Germain Pinel

Share this post:

San Serriffe typographic Island

San Serriffe typographic Island Design, creativity and oblique strategies!

Design, creativity and oblique strategies! Tote bag, a new social totem?

Tote bag, a new social totem? Sister Corita Kent, the Pop Art nun

Sister Corita Kent, the Pop Art nun Donald Trump, the martyr who makes history

Donald Trump, the martyr who makes history Graphic charter for Soletanche Bachy

Graphic charter for Soletanche Bachy YUV® hair colour device – branding, naming and visual identity

YUV® hair colour device – branding, naming and visual identity Croix-Rouge insertion

Croix-Rouge insertion Brest Bretagne Handball – Brand identity

Brest Bretagne Handball – Brand identity Conférence des Présidents d’Université – Visual identity

Conférence des Présidents d’Université – Visual identity Hans Hillman, “poster art without fuss”!

Hans Hillman, “poster art without fuss”! DNA and advertising marketing

DNA and advertising marketing The branding of a social movement: Collages against feminicides

The branding of a social movement: Collages against feminicides Burberry regains prestige with a new antique logo

Burberry regains prestige with a new antique logo Poster of the humanitarian trades fair

Poster of the humanitarian trades fair

Leave a Reply