The genius of Iranian graphic design

Graphic design in Iran

A little while ago now, we started a series of articles entitled “Graphic design around the world“. The idea was to take a look at other graphic design cultures, to travel to meet colleagues, to discover the history of graphic design in their countries. It is indirectly about questioning globalization, standardization and the conditions of exercise of our profession.

The first country we explored was Turkey. Today, we are taking a leap of faith to visit the genius of Iranian graphic design. We are talking about real genius here, for its extraordinary creative faculties, and by analogy with the genius of the lamp: endowed with great power, who only asks to be freed from his chains to shine.

It is certain that the recent international tensions are not for nothing in our desire to meet Persian design. Faced with the American embargo and the terrifying idea of yet another war, it seems essential to us to go and meet the other, his culture, his history. And what an incredible story that is the history of Iranian art and design!

We will of course add our sincere thoughts to the Iranian people, also heavily affected by the Coronavirus. May this article give them a modest reason for optimism and pride in these troubled times. For our part, we have taken great pleasure in travelling through the graphic history of their country. Thank you to all the designers who expand the boundaries, even if they are only imaginary.

The work of a designer or artist in Iran today cannot be understood without context. This context is that of a country that is magnificently rich in the arts, and so special in the world. Once a Persian Empire, Iran has been crossed and nourished by countless cultures and civilizations. It has distinguished itself around radiant artistic faculties and a distinct language. Contrary to what one might think, Iran is not an Arab country, and has more cultural affinities with India.

In turn influencing the world during antiquity, open to the West in the 1960s, then reclusive during the Islamic revolution of 1979 before opening up timidly again, the country has gone through more or less dark and propitious times for visual expression. In spite of the bad image conveyed in the media related to current events, Iran is nonetheless a high place of artistic and graphic creation, recognized on the international scene, and full of talent.

Before delving into contemporary Iranian graphic design, we must therefore understand its history.

A 3000 year old visual heritage

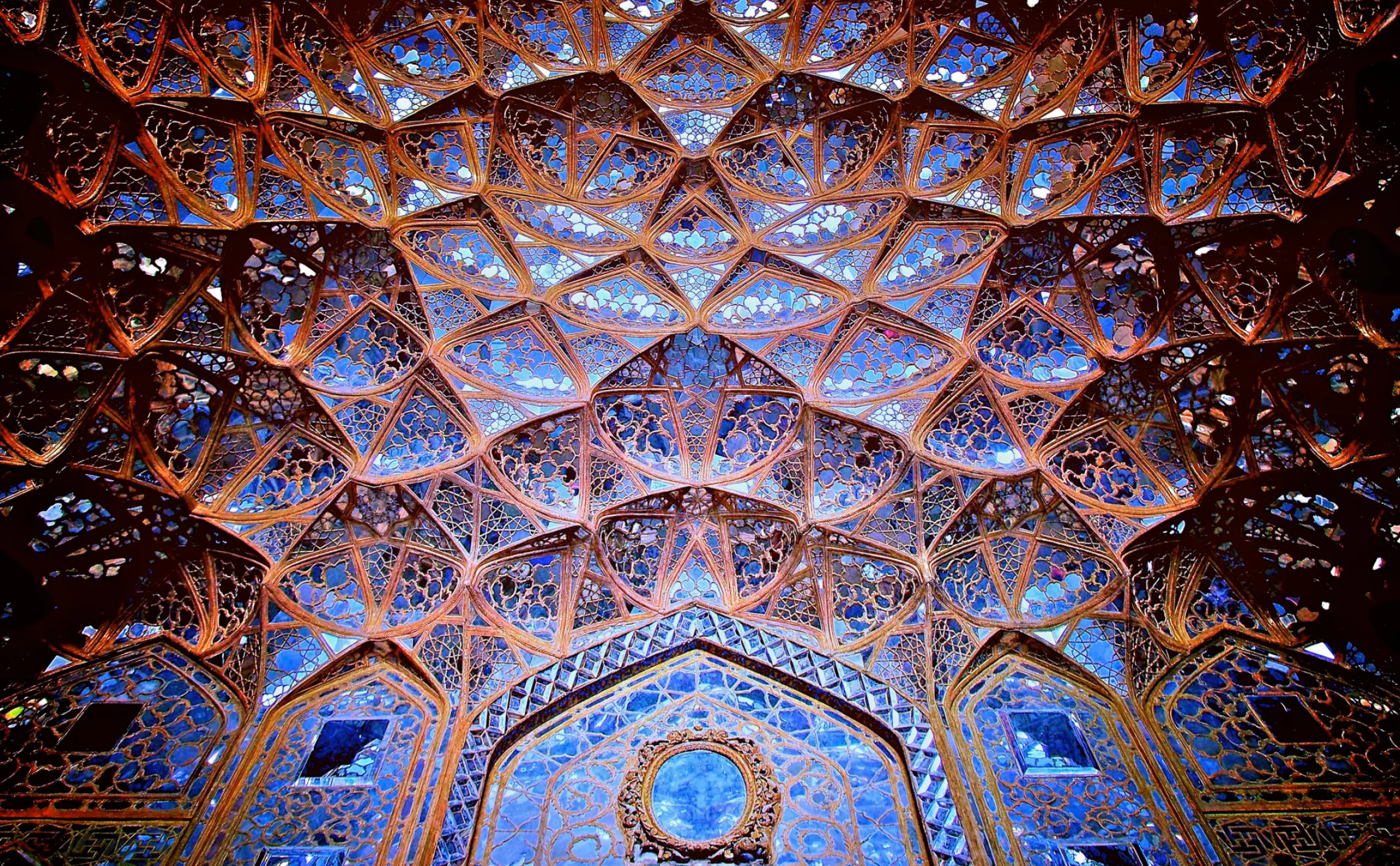

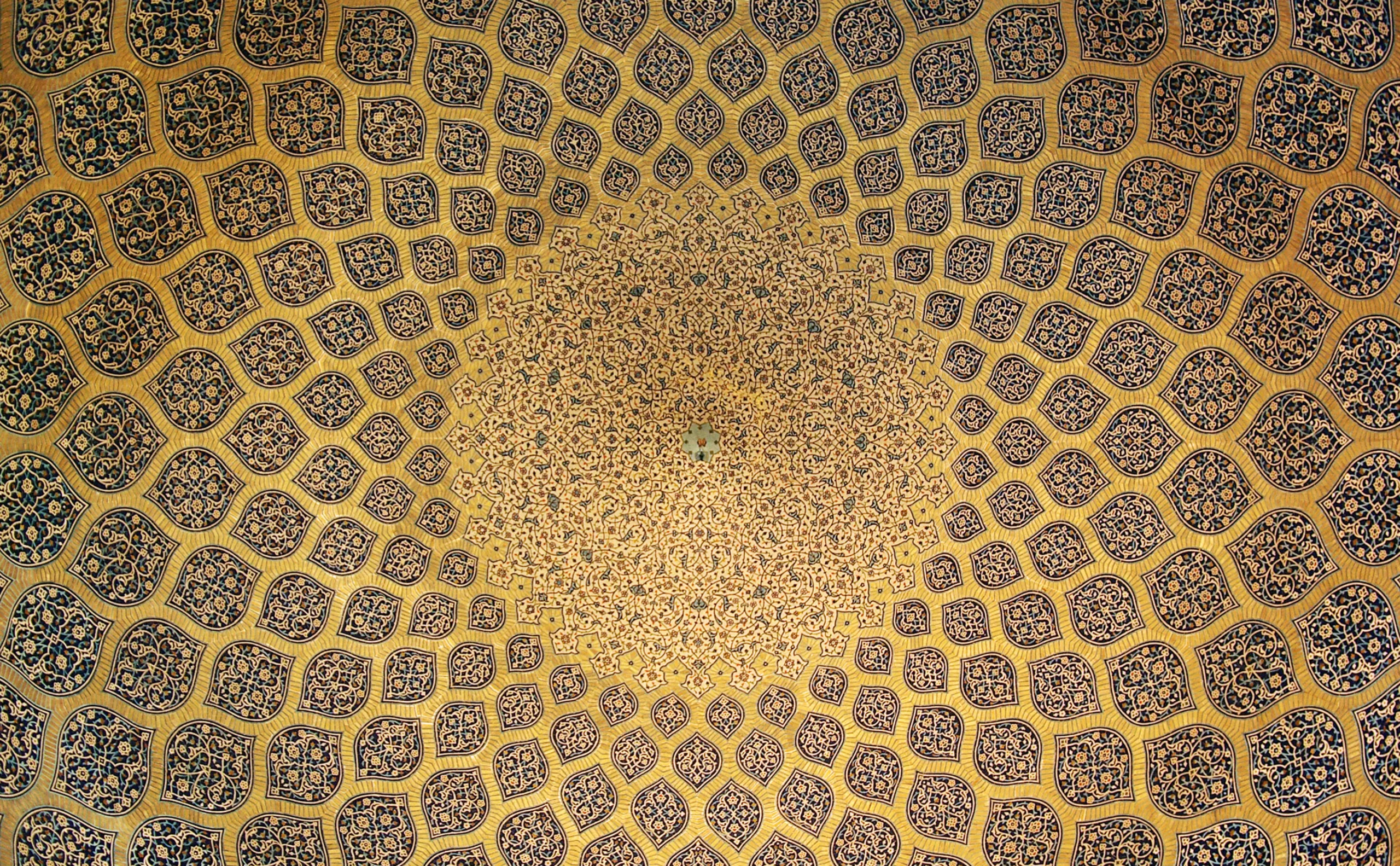

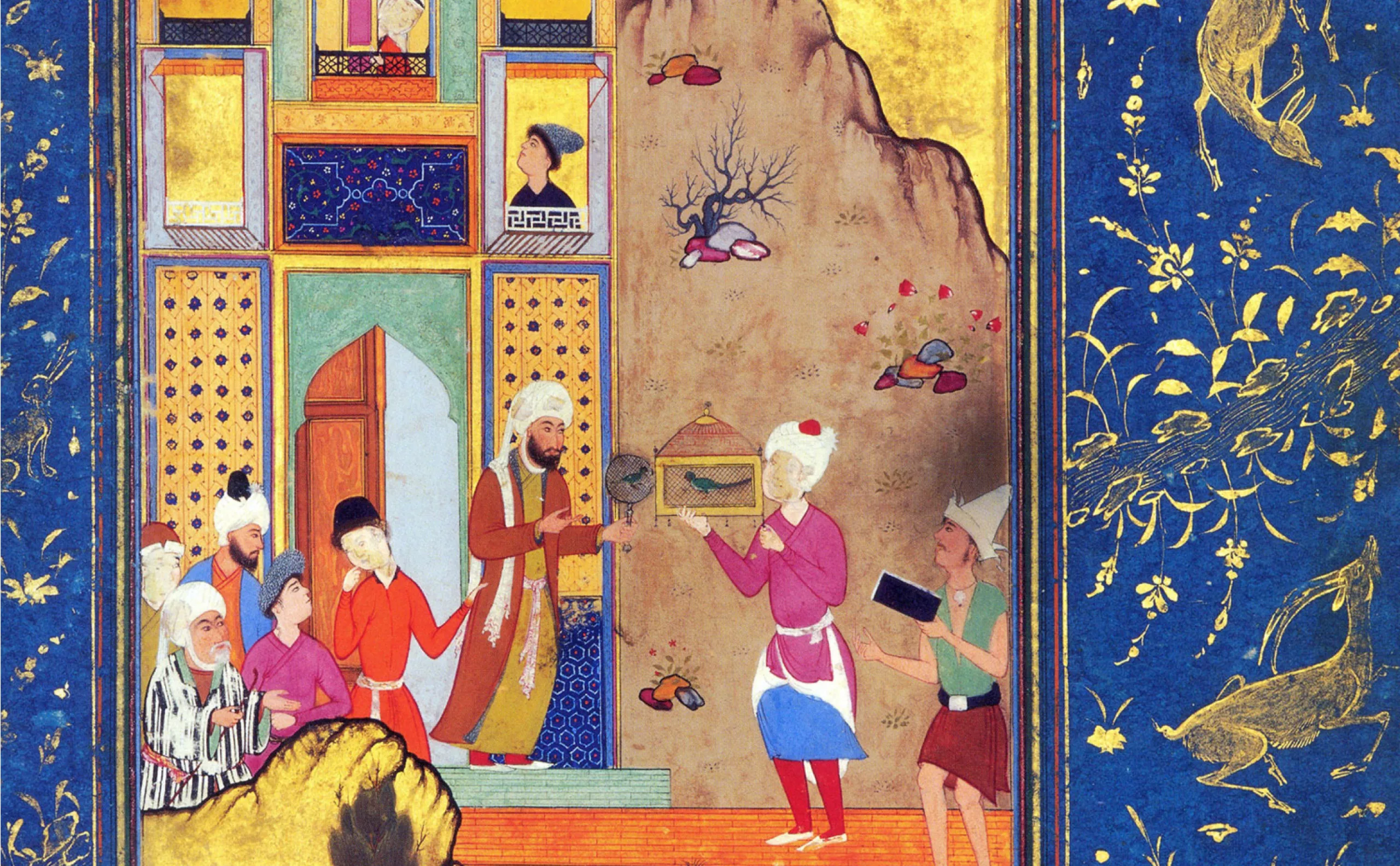

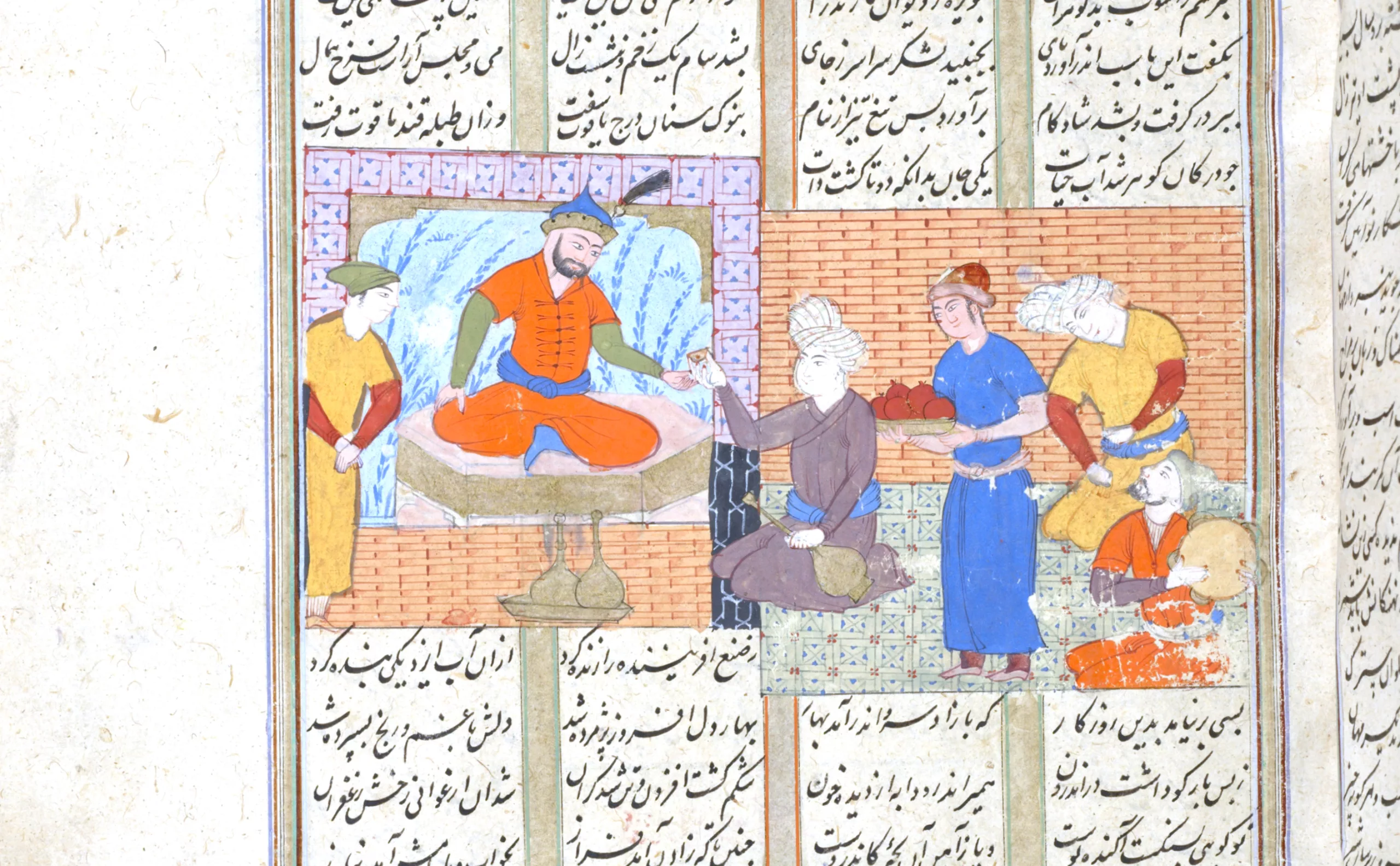

Brewed by conquests and civilizations that have shaped the world’s largest empire and the tales of the 1001 Nights, Persia and Iran have been nourished by cultural crossbreeding to become one of the most artistically prosperous countries in the world. This can be seen in the quality and diversity of the arts that have endured over the centuries and are the foundation of our societies today. The miniatures, those minute, richly detailed paintings, Tazhîb illuminations, poems, ceramics, enamelling, engraving and tapestry that take up traditional motifs are an integral part of Iranian culture.

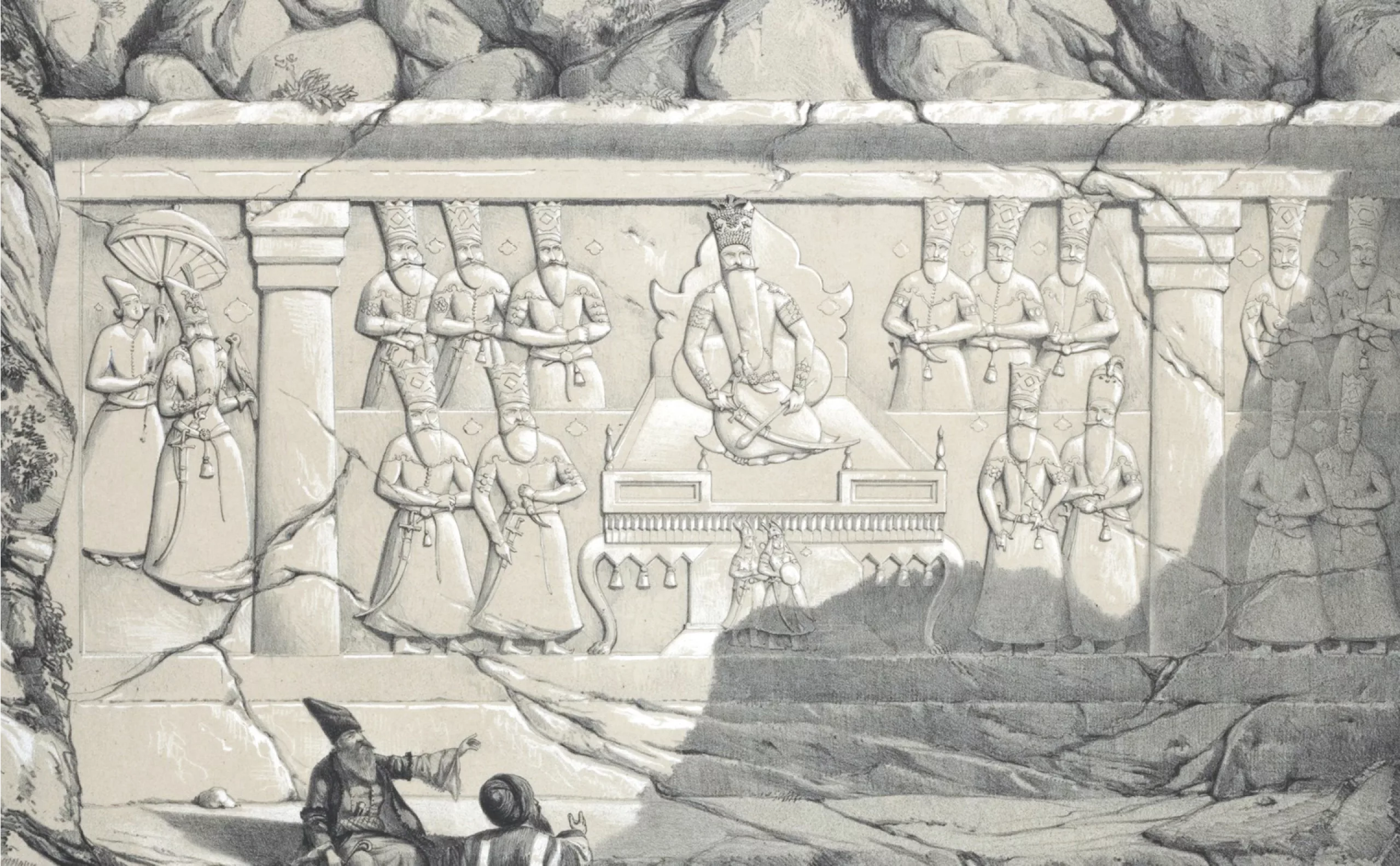

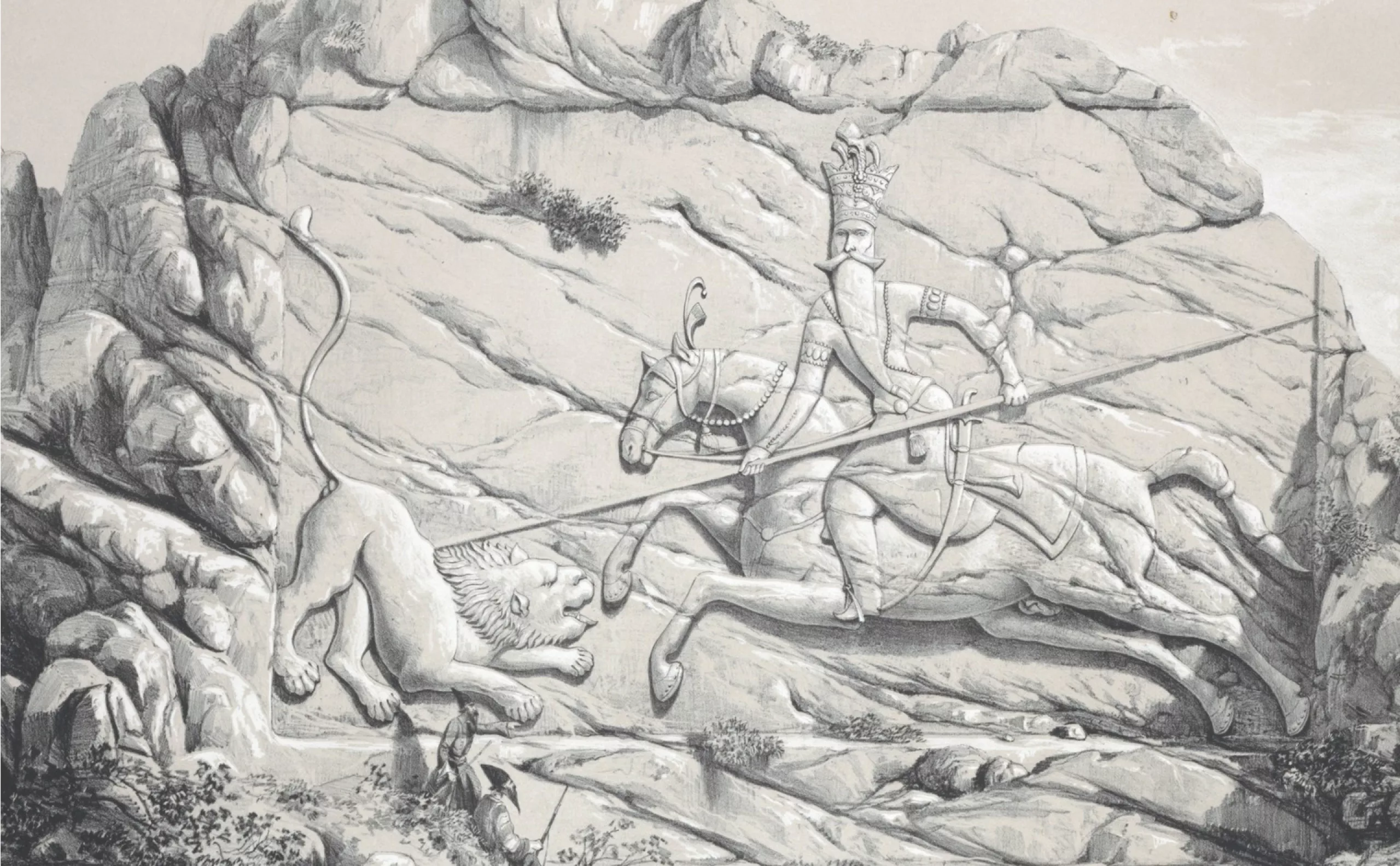

An article written at the end of the 1950s on the occasion of the second Tehran Biennale boasts of the Persian heritage and its influence: “Historians no longer ignore the fact that Romanesque sculptors in Europe were inspired by Sassanian bas-reliefs, that Chinese artists did not remain insensitive to Iranian interlacing and decorative forms, that our miniatures taught the world the perfection of lines and clarity of colour, and that our art played a role as an intermediary between artistic currents from the farthest reaches of the Eastern world to the farthest reaches of the Western world. “

The Achaemenid Empire, the first great Persian empire and the largest empire in the ancient world, extended in the 5th century BC from Greece to Egypt to the outskirts of India and China. It was divided and segmented under Alexander the Great, then expanded again during the Sassanid Empire (around 220 AD). Its fame is such that it culturally influences and shapes the arts, architecture, culture or writing of the surrounding civilizations: Rome and Byzantium, Western Europe, Africa, China and India.

Let’s stop for a few seconds on Alexander the Great. We are in the 3rd century BC. His dream of merging the Greek and “Eastern” civilizations will lead to the development of the Hellenistic civilization (Cf: the Western civilization). The role of art in Politics and Society began with him, and in particular with the development of portraiture. In order to control an empire that required several weeks of travel on horseback to cross it, Alexander entrusted artists with the task of producing innumerable representations of him, frescoes, mosaics, sculptures… and especially money. He will be the first monarch to strike coins in his effigy in his lifetime! All these representations embodied power in the physical absence of the king. Before him, gods were sculpted to embody divine power. This strategy of omniscient presence and incarnation of power will certainly facilitate the mastery of the immense territories conquered by Alexander. In contemporary terms, one could almost speak of the invention of “branding” or at least “personal branding” by Alexander the Great.

Portraits of Alexander have crossed the centuries, and are still today a great success with politicians, some busts still adorn the Senate Gallery in Paris for example. The image becomes a tool of power. A large part of the western visual tradition will come from Alexander the Great.

Alexander the Great’s dream of the union of East and West will come to an end a few centuries after his death with the arrival of the Sassanid Empire. And the eastern Persian tradition will regain its rights in Iran. But Alexander the Great still remains a hero in Iran, and the Iranians refuse to see him as a conqueror. From our point of view, 23 centuries later, it seems important to us to remember that there are bridges in history that can bring East and West closer together. Long live the bridges!

Text as image

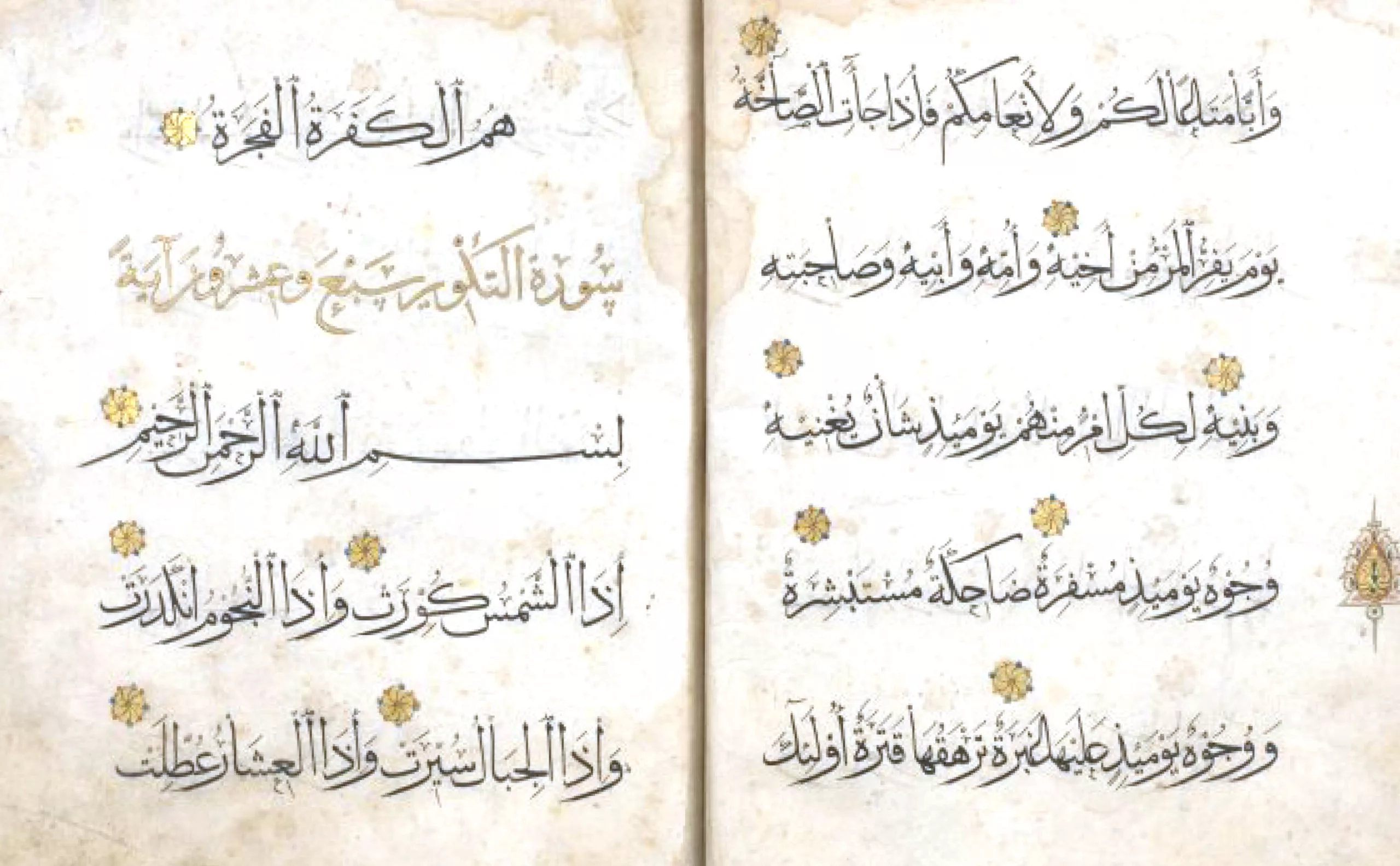

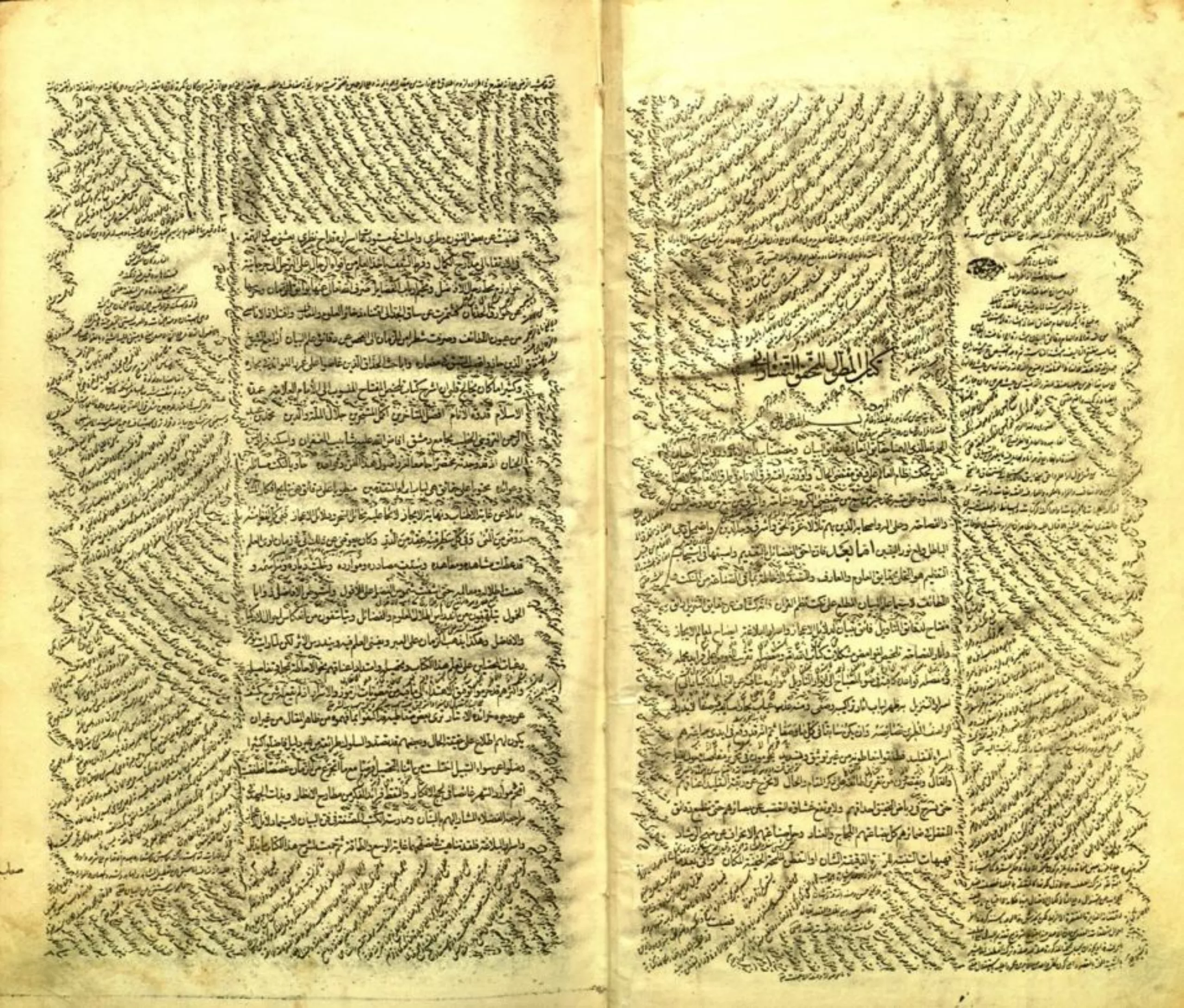

The text also has a big say in this visual baggage. When the Prophet Muhammad recites the Koran, the sacred text of Islam, a huge work of memorization through writing will be done. As Iranian researcher and graphic designer Sina Fakour explains, “between the eighth and eighteenth centuries, before the appearance of the printing press, the number of handwritten books in countries using the Arabic alphabet was unprecedented and uncountable. Today, more than 3 million manuscript books from this period are preserved in libraries and institutes”.

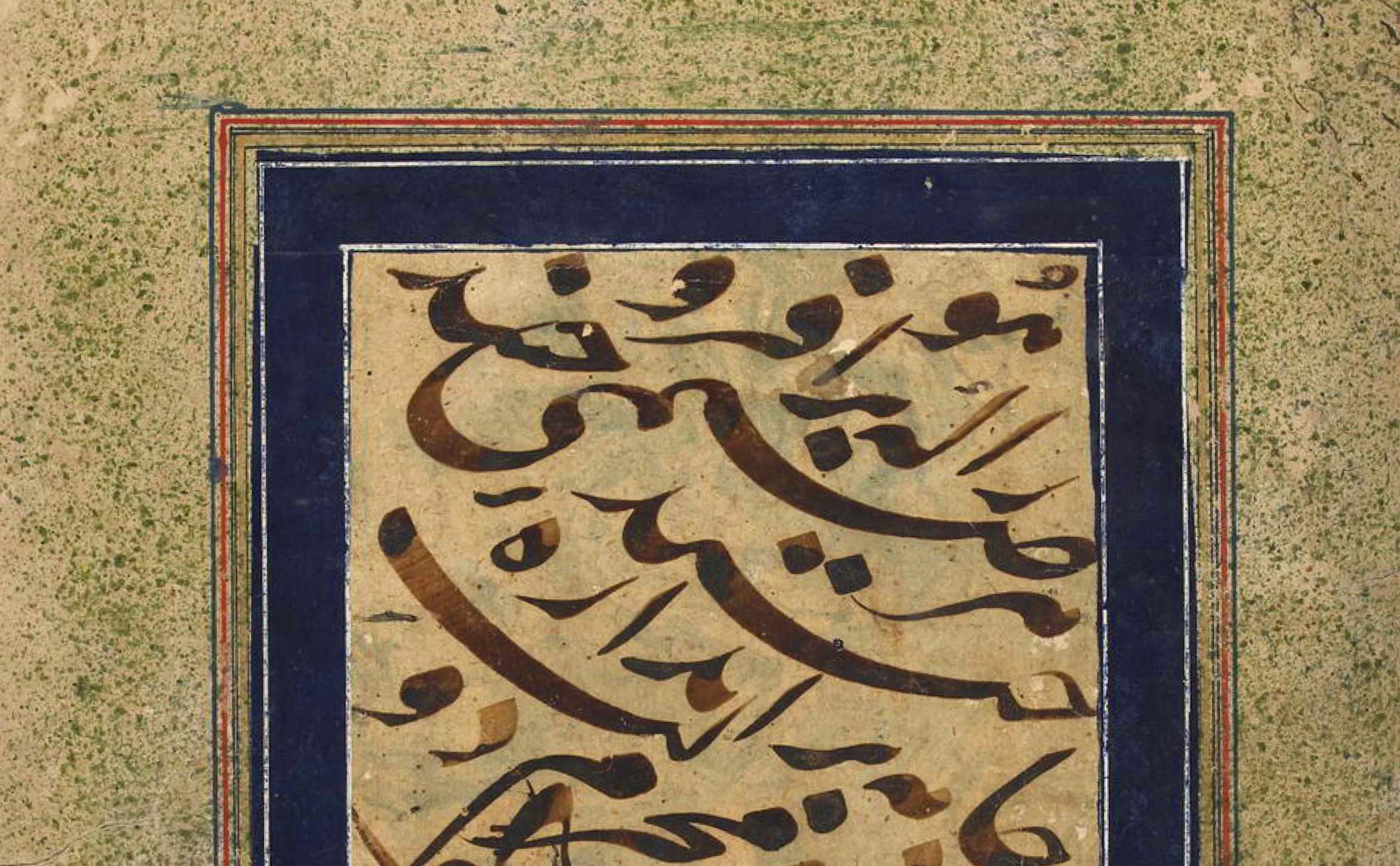

Based on the Koran, the Muslim religion produces a large number of miniatures depicting characters. Little by little, the representations of faces in pious texts disappear and are left empty. The words of the Koran are then used as a pretext for particularly devoted ornaments. Illumination and calligraphy thus sublimated the sacred words in the early books, with gold, ink and paper sets. So much so that the art of calligraphy is still considered to be the most accomplished of the applied arts of Islam, and is widely used in Iranian graphic design.

Below are some excerpts from Shahnâmah, the Book of Kings, calligraphed by Firdawsî in 1616. Also some calligraphy excerpts from the Koran, between 1300 and 1500.

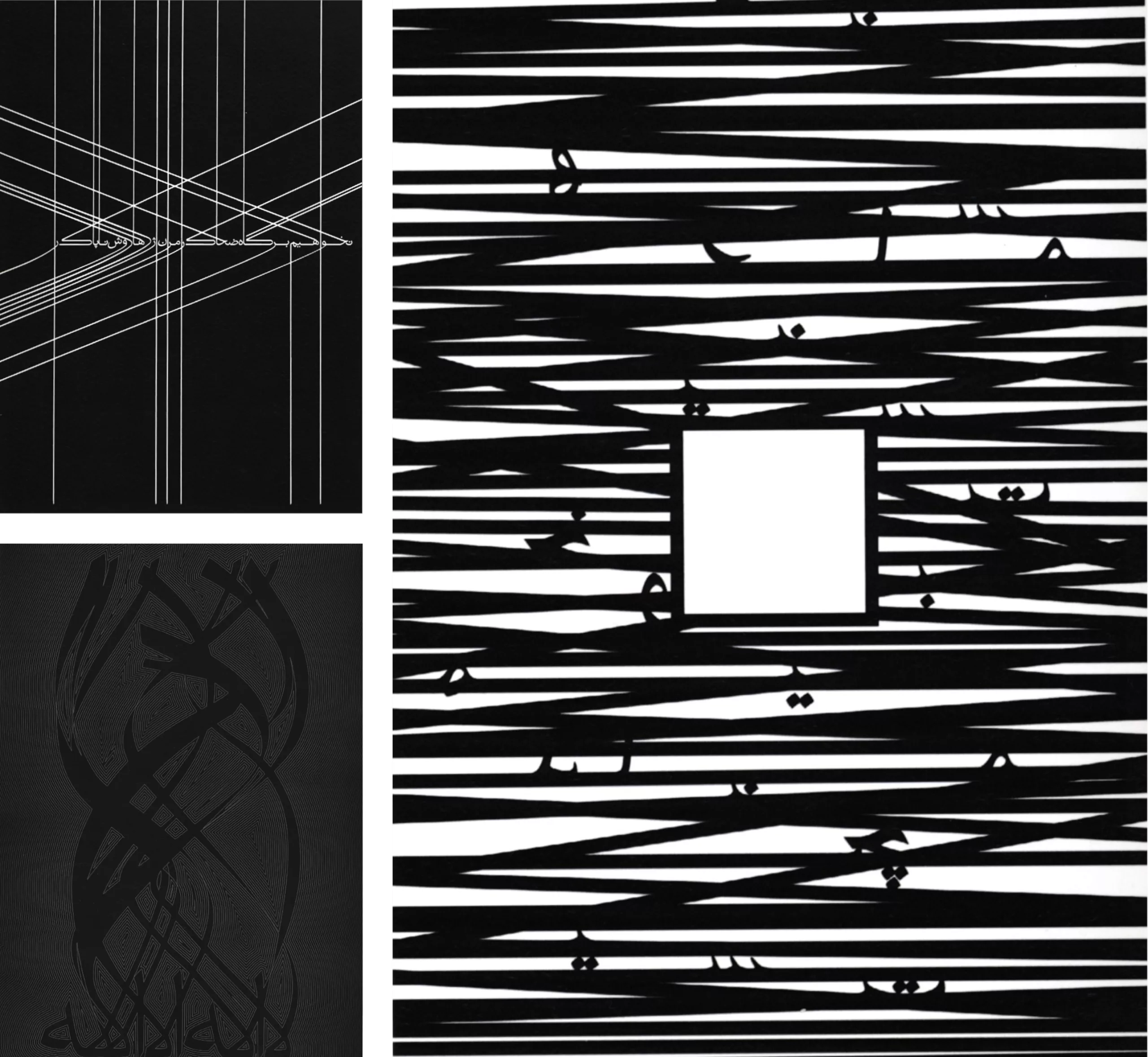

In line with these traditions, the text is very often stylised even today, and is an integral part of the graphic composition. It is a major element, even supplanting the visual (whereas it is mostly the opposite in our culture). Words and images intermingle to become one, the letters become illustrations. One cannot grasp the meaning of Iranian graphic design without taking into account the importance of the text for this culture.

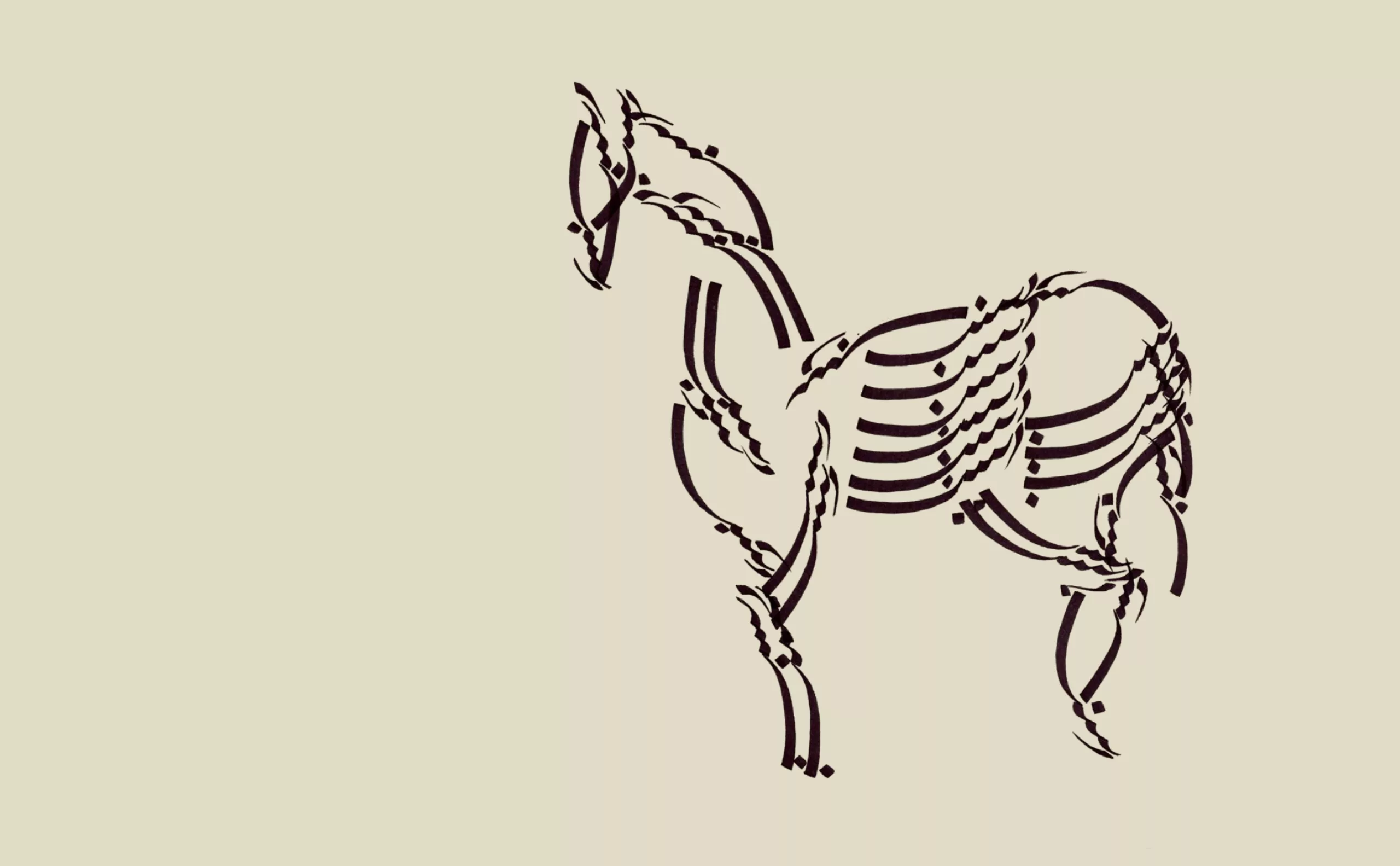

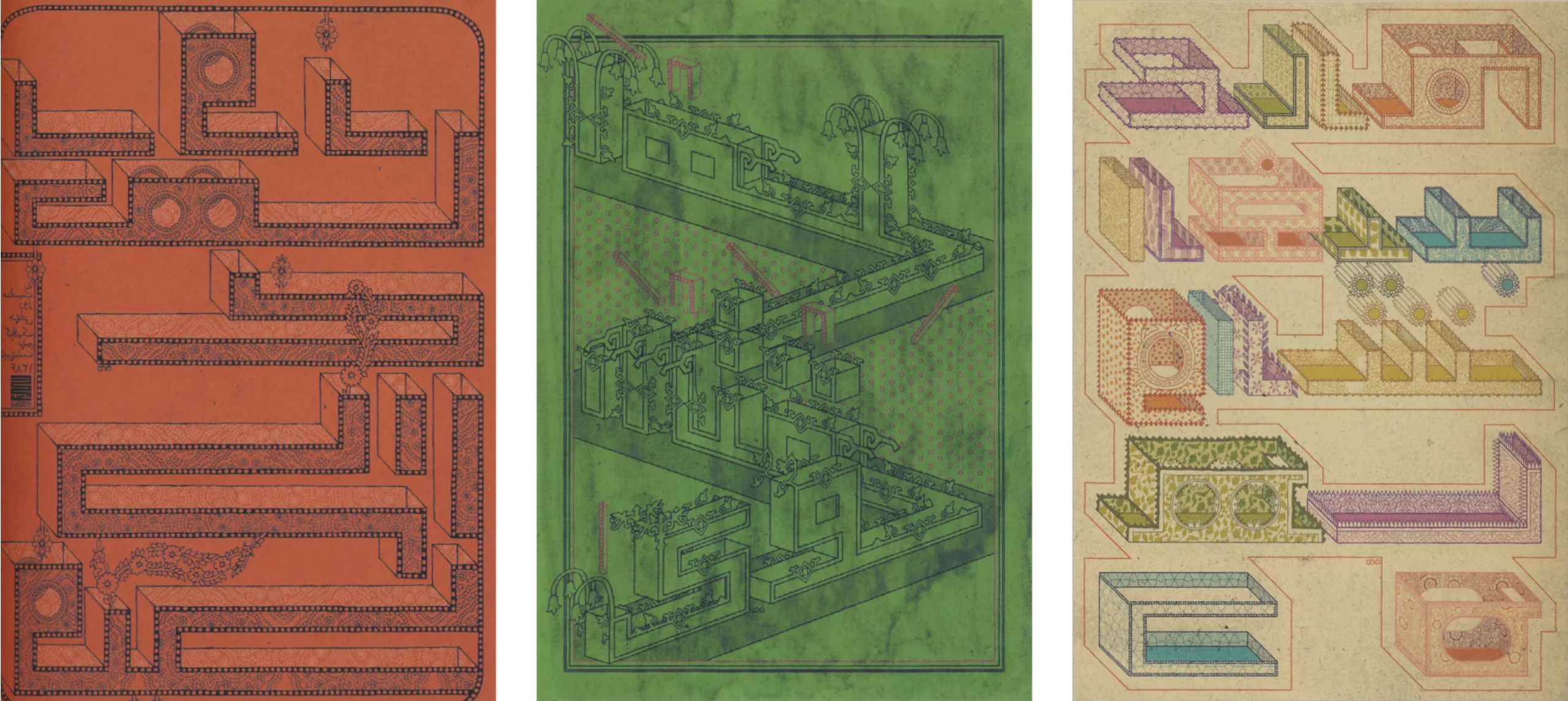

Below is an overview of the calligraphic work of the Iranian designer and visual artist, Parastou Forouhar. Born in 1962 in Iran, she has been living in Germany since 1991: her parents were murdered in Iran because they were considered opponents of the regime, and she currently lives in exile. Her work is a criticism of the Iranian government, and she also questions the notion of identity and women’s rights.

In this series of drawings, Forouhar composes with his art of calligraphy the names of animals in Farsi (Persian). She compares the ambiguity that surrounds the question of whether we are looking at an image or a text to the feelings of belonging and strangeness she felt when she was labelled as “the Iranian” by her German colleagues. The elegance and visual simplicity of the drawings beautifully capture the act of trying to communicate in another language and across cultures. This attempt is traced with simple things and the combination of non-verbal and written modes of communication, to convey not only meaning but also feelings.

The last image is a work of meaningless letters drawn on a sacred Hindu cow, which carries these letters harmoniously, to illustrate the two great religions that are tearing Indian society apart.

Typography and printing

At the same time, Arabic typography -mechanical, unlike its calligraphic, manual cousin- took much longer to develop than in the West. For good reason; the Latin alphabet takes the letter as a unit, whereas it is the word as a whole that counts in Arabic and Persian writing. Moreover, we would like to point out that the Persian (or Farsi) language uses the Arabic alphabet, but is not an Arabic language. It is spoken in Iran, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan or Iraq among others, but by three times fewer speakers than Arabic. Farsi once had its own alphabet, until the British banned its use in the 18th century. The word Farsi comes from the Persian word / parsi, but the letter P does not exist in the Arabic alphabet, so the word Farsi was chosen.

Iran has almost always used lithography to print its texts, even in the age of printing and digital technology; that’s how much the Persian language is coming up against this technology. The first to tackle Iranian typography in the aspect of letters as forms was Reza Abedini, to whom we devote a separate article in our History of Graphic Design section.

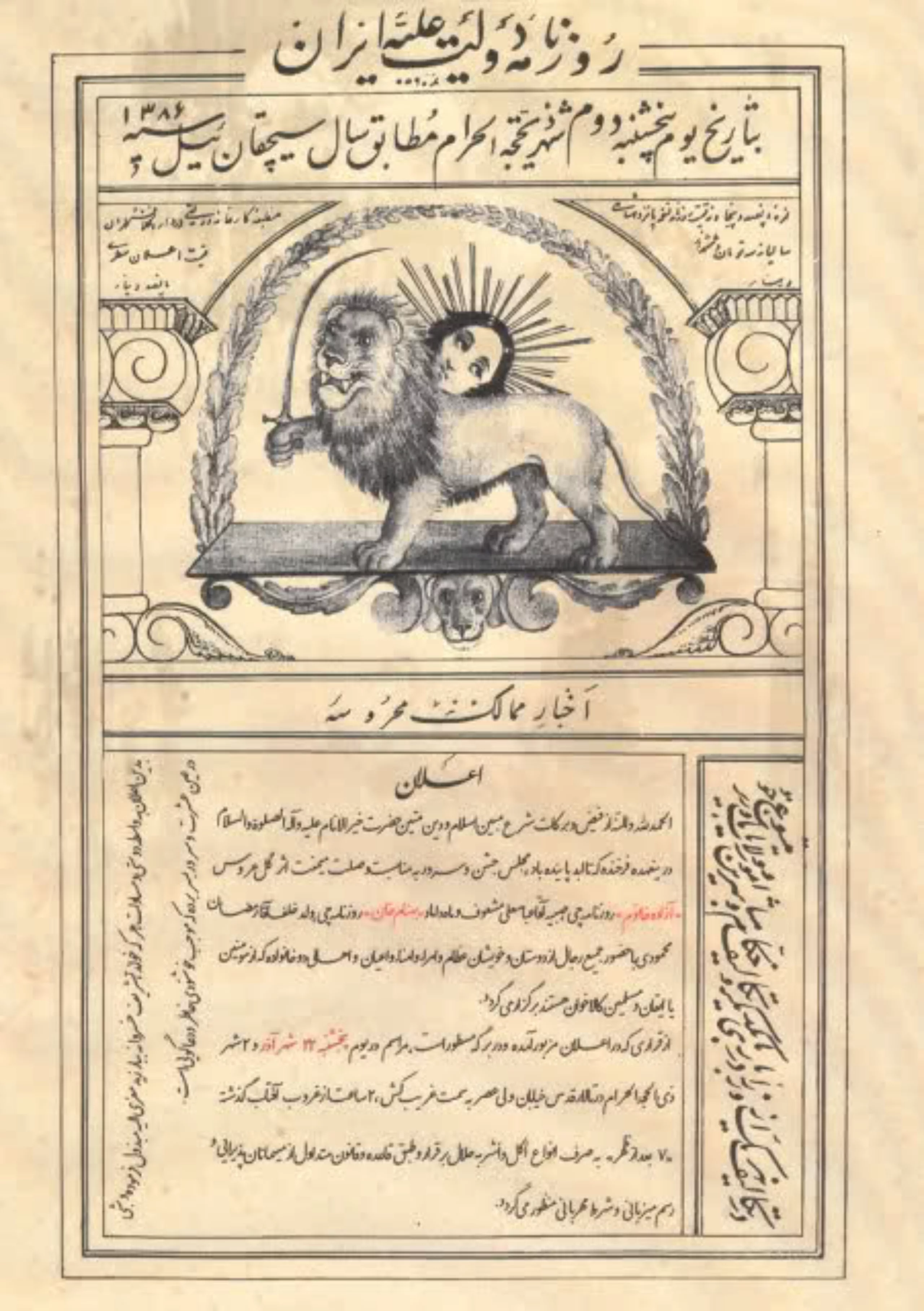

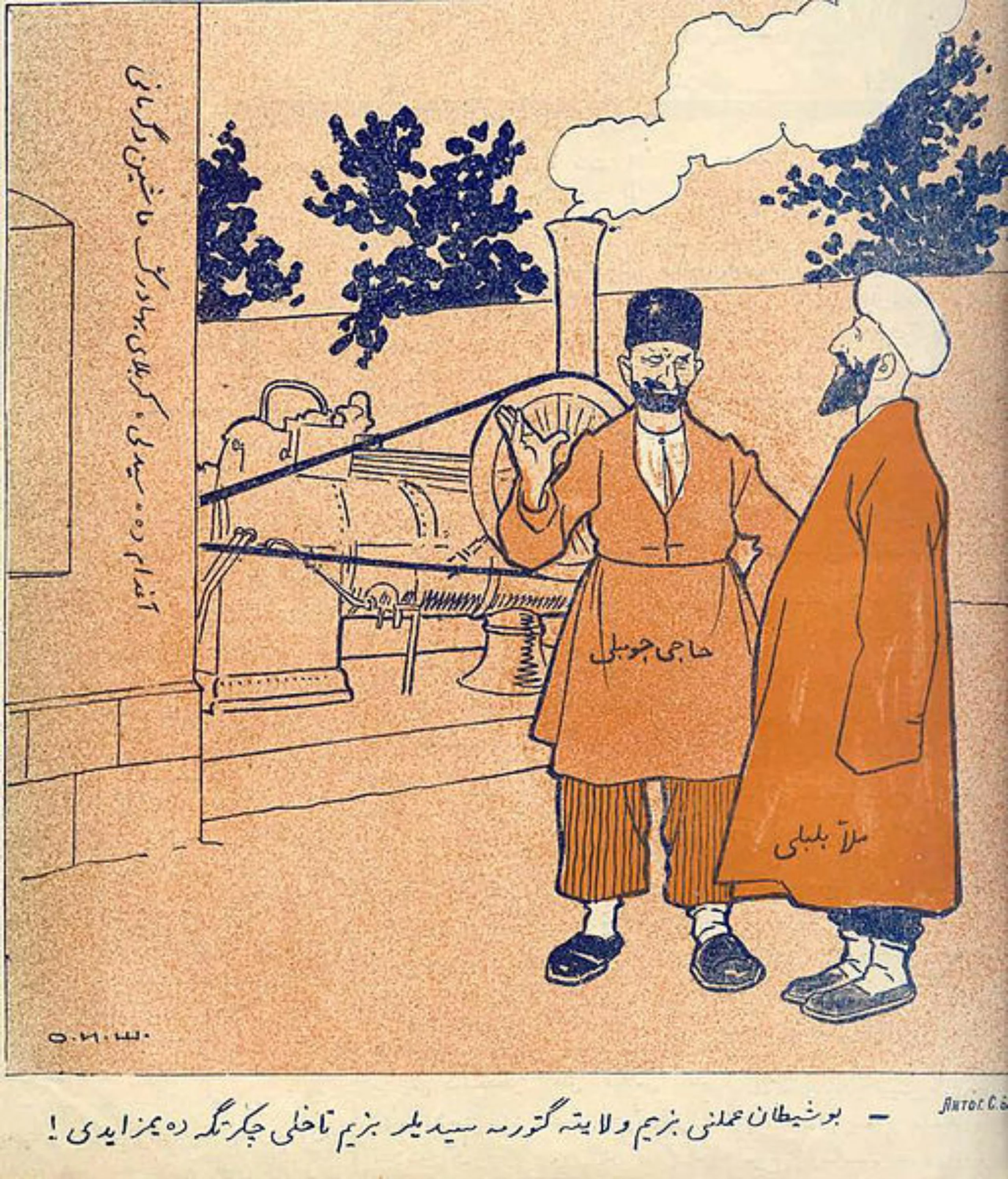

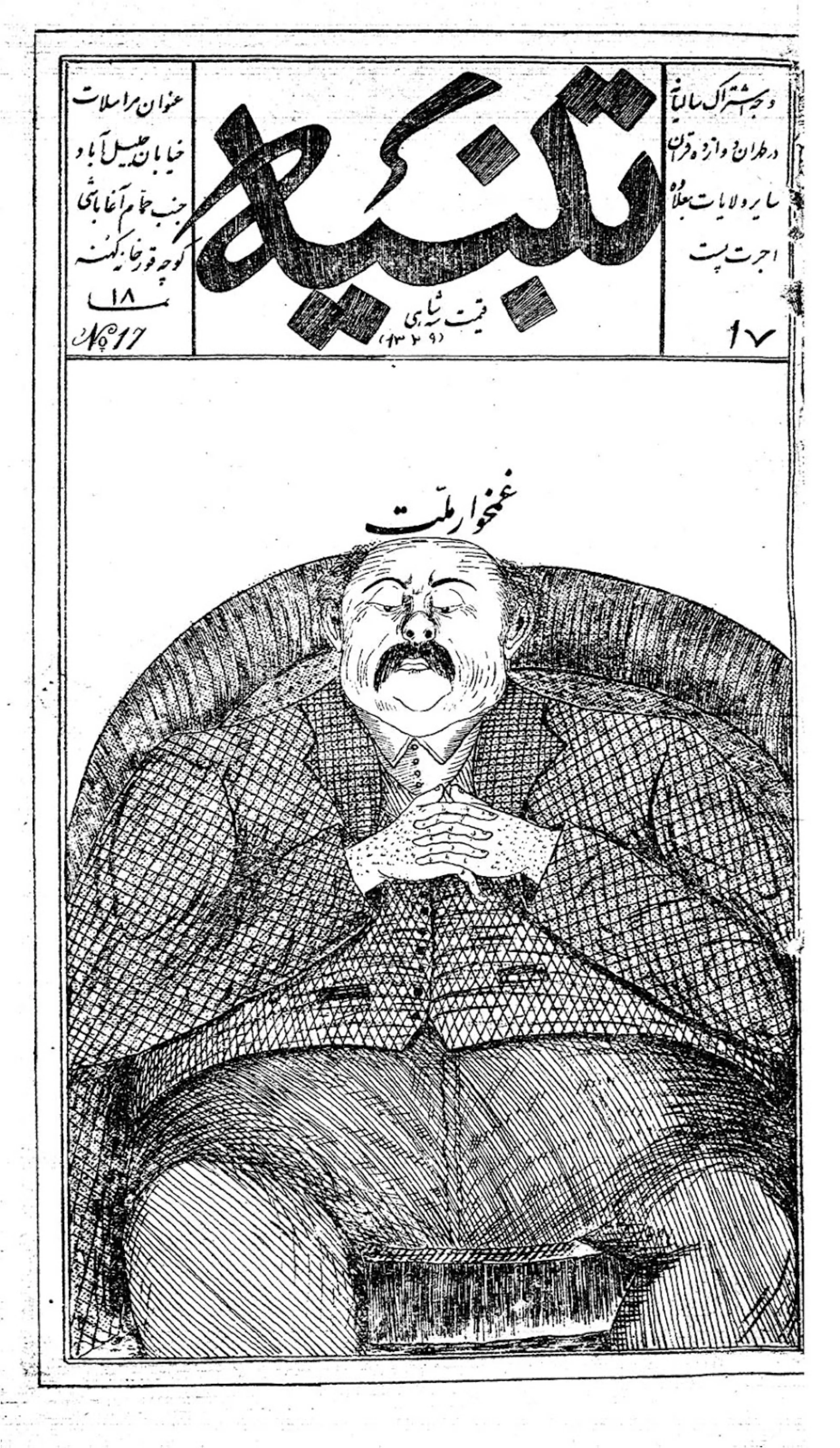

The first lithographic printing press arrived in Iran in 1821, just two years after the technology was introduced to the United States. By drawing on a stone, this medium allows artists to manually compose motifs, caricatures and calligraphy without the constraints of typography or layout, and at a lower cost than conventional printing. The first book was printed 11 years later – in lithography – and many European publications were translated in the wake, in a move towards modernisation and openness to the world. Newspapers will then use this technology.

The first graphic designers

Contemporary graphic design was born in Tehran at the beginning of the 20th century. In 1941, Tehran University offered a section dedicated to Fine Arts, with specialized courses in graphic art and design. The Ministry of Culture and Arts later developed a Decorative Arts section, inspired by the National School of Fine Arts in Paris. Bauhaus and applied arts are taught there. Iranian students thus have a path that begins with fine arts before leading them to graphic design, such as Morteza Momayez, and Reza Abedini after him.

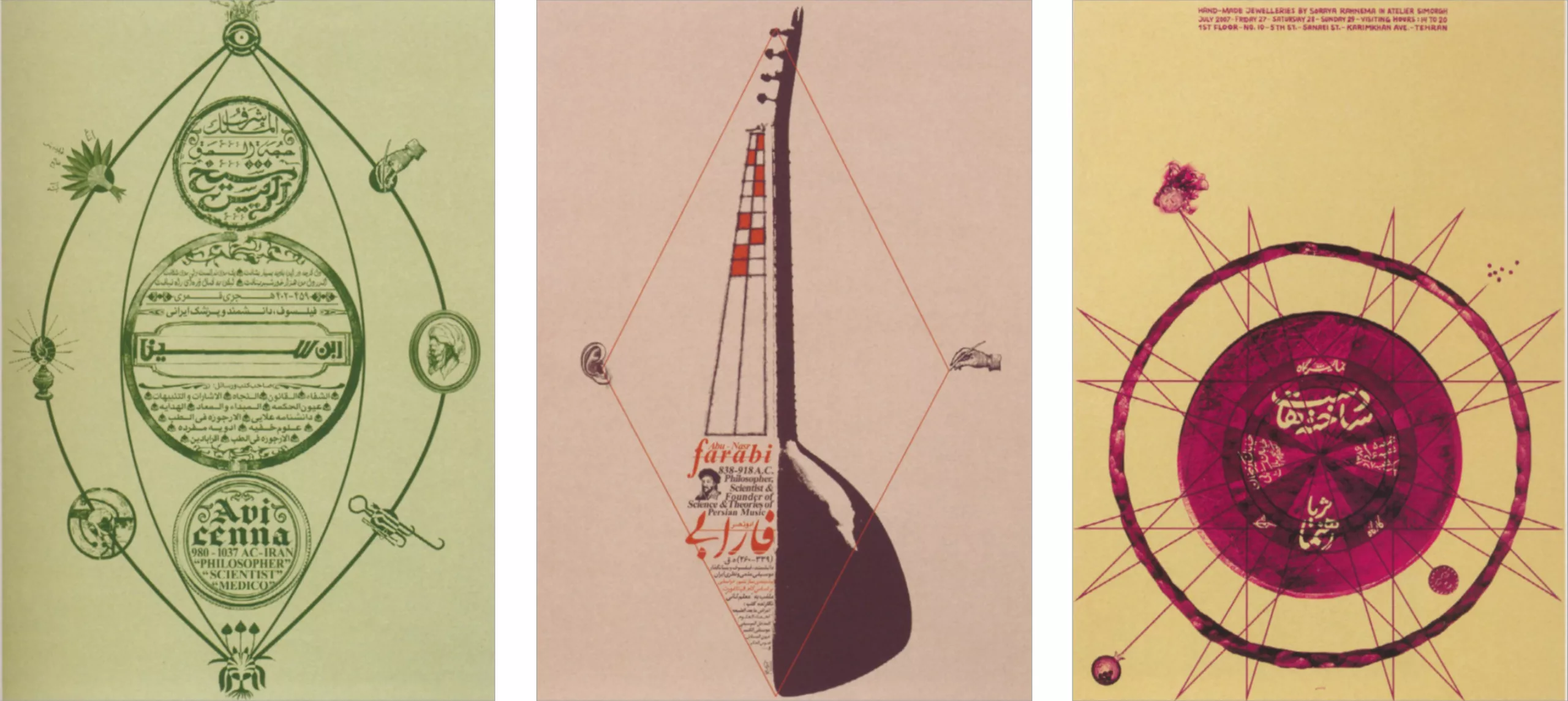

Morteza Momayez and some of his contemporaries in the 1960s (Guity Novin, Farshid Mesghali, or Ghobad Shiva) constitute the first generation of Iranian graphic designers.

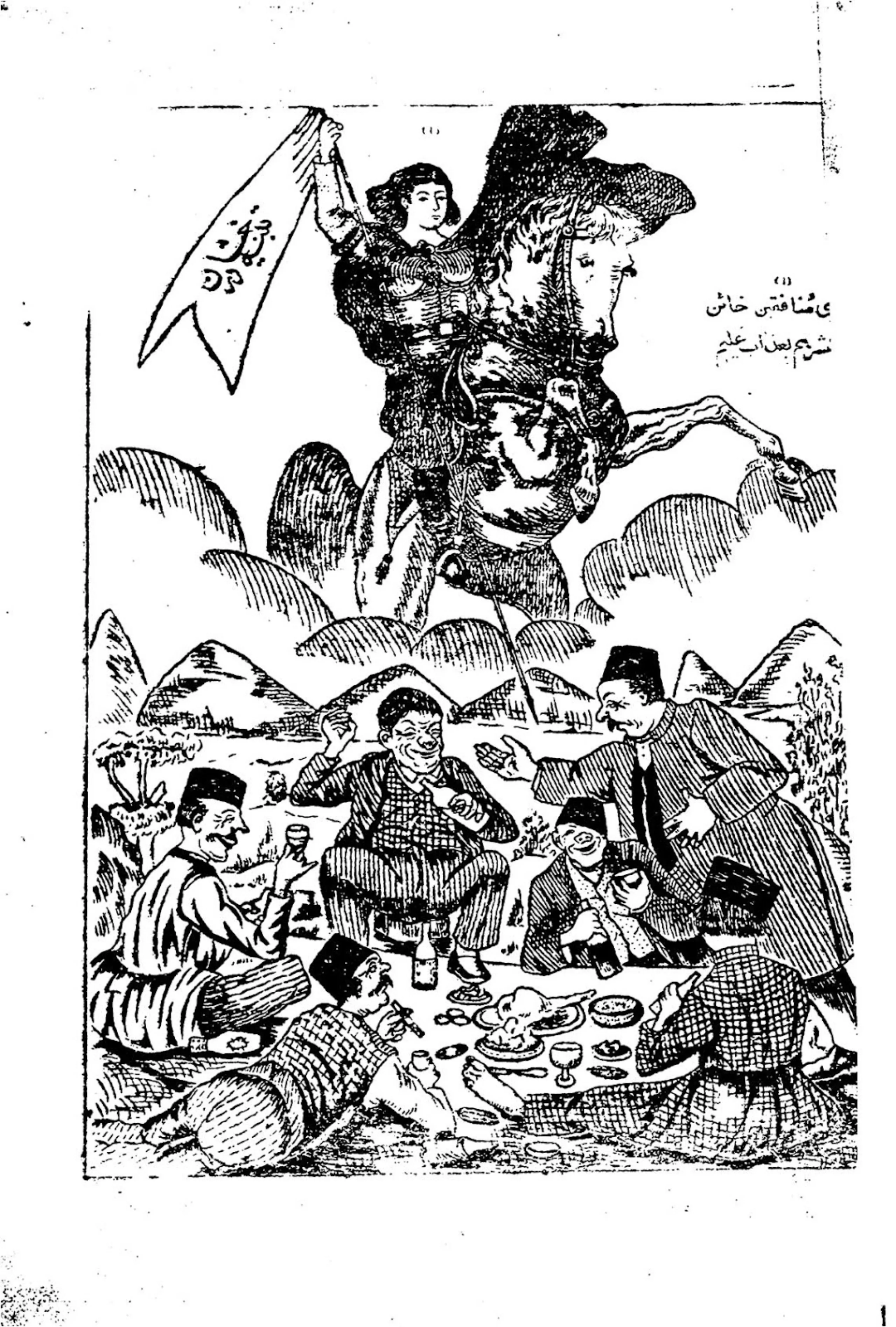

Trained Western-style in an extremely rich culture, they refuse to give in to the blackmail of purely mercantile and advertising orders, and create their own visual grammar. And this despite the fact that the majority of private clients are satisfied with plagiarism in European or American styles. Curious, informed, also inspired by the great graphic currents of the West, in technical and creative research, their practice is centred on the analysis and presentation of visual solutions to a communication problem. Many magazines or progressive cultural institutions – such as Kanoon, which organized festivals to promote children’s books and animated films – allow them to freely create creative visual supports, and are financed by the Shah’s regime.

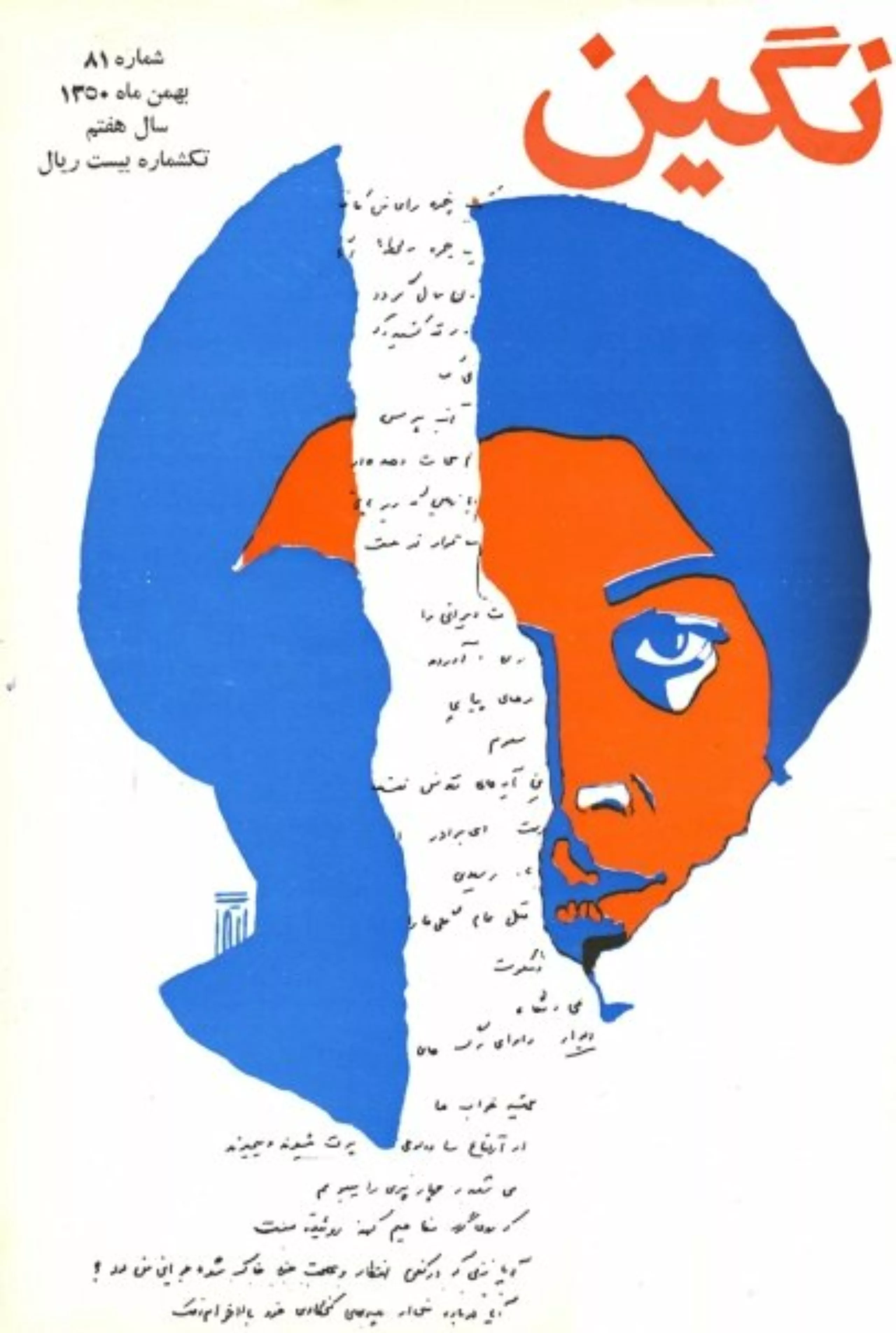

Below is the work of Ghobad Shiva:

At the time, these designers were true pioneers. With their own style, they tried to make people understand that design, even if it is representation, does not hide the essence of things. Luckily, Iranians, and therefore many of their clients, are educated and sensitive to art, and graphic design is considered an art in its own right. The first graphic exhibition in Tehran took place in 1964, and the first Biennale of Asian Art was held in the Iranian capital in 1978.

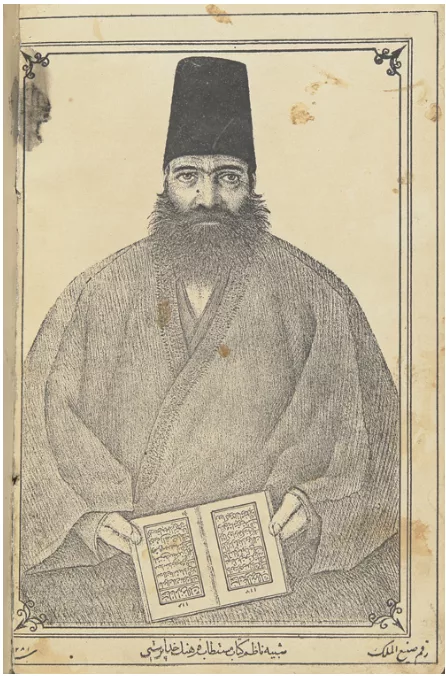

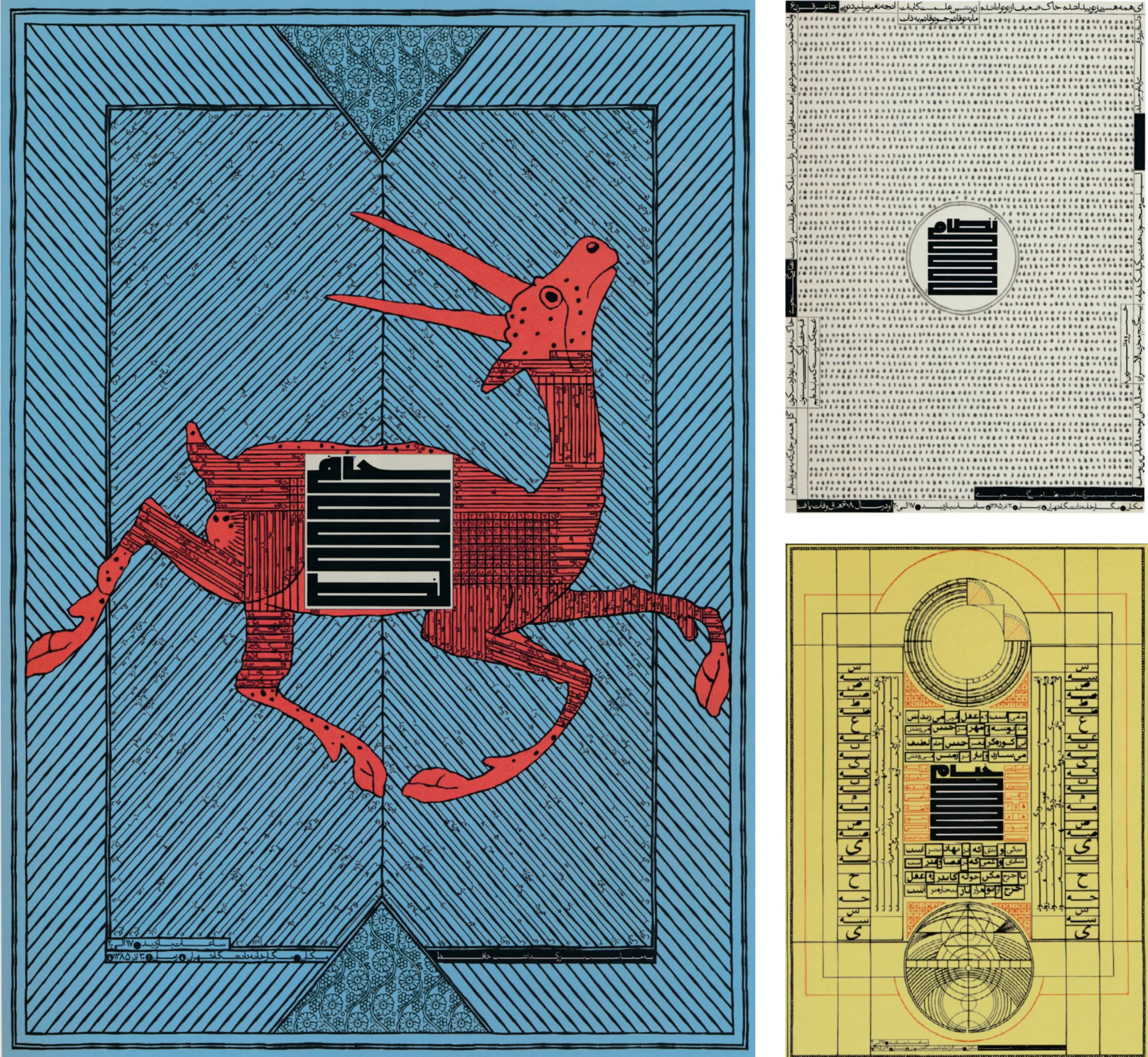

Momayez studied and worked in Iran in the 1950s and then trained at the Arts Déco school in Paris in the early 1970s. He then teaches the discipline in Tehran, and presides over the society of graphic designers at the origin of many biennials and local and international exhibitions. Influenced by the Polish poster, the cultural richness of his country and his studies in France, he plays an indispensable role in the local graphic scene. Moyamez is the first Iranian to become a member of the International Graphic Alliance. Here are some of his posters from the 1970s.

A rare and therefore notable fact, a woman manages to make a name for herself in this closed and almost exclusively male universe: Guity Novin. Hired at the Ministry of Culture and Arts, she is nevertheless confronted with the refusal of the director of the graphic arts department, who would prefer her to be a secretary. New wave filmmaker Hajir Darioush then offered her a position in the film department. There she designed the visual material for the first Tehran International Film Festival.

Women have contributed in their own way and for centuries to the development of Iranian arts and culture, firstly through “feminine” textile-related activities such as weaving. Today, more than half of university graduates and artists and designers in Iran are women.

They are graphic designers, creators, lecturers, lead international workshops or run art and design galleries. Today we can mention the graphic work of Homa Delvaray, Zeynab Izadyar, or Mahsa Gholinejad of Studio Tehran, among others. We show some of them below.

The Islamic Revolution and Censorship of the Arts

But in 1979 everything changes. The Islamic revolution deposed the Shah and established a strict Islam and a ban on the arts, which were considered heretical. You have to read Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi to understand: goodbye Abba, the Nike and Michael Jackson, goodbye Western culture! Many artists -including Novin- are fleeing Iran. Two years earlier, however, Empress Farah Pahlavi had inaugurated the TMoCA (Teheran Museum of Contemporary Art), a unique museum in the Middle East inspired by the Guggenheim, with the largest collection of contemporary art in Iran and the largest outside Europe and the United States.

Warhol, Moore, Dali, Chagall, Lichtenstein or Raushenberg, judged anti-Islamic or pornographic, are stored in a basement for 20 years, until the first post-revolutionary exhibition in 99. In spite of a more or less variable tolerance, the current regime still lets these works sleep most of the time in the shadows while waiting, one day, for new hours of glory…

Coming out of the shadows

During the revolution, artists in exile created from their host countries and sometimes returned to their home countries in the 1990s. Others like Morteza Momayez contribute to maintaining and developing the creativity of his country in isolation despite the revolution and then the Iran-Iraq war.

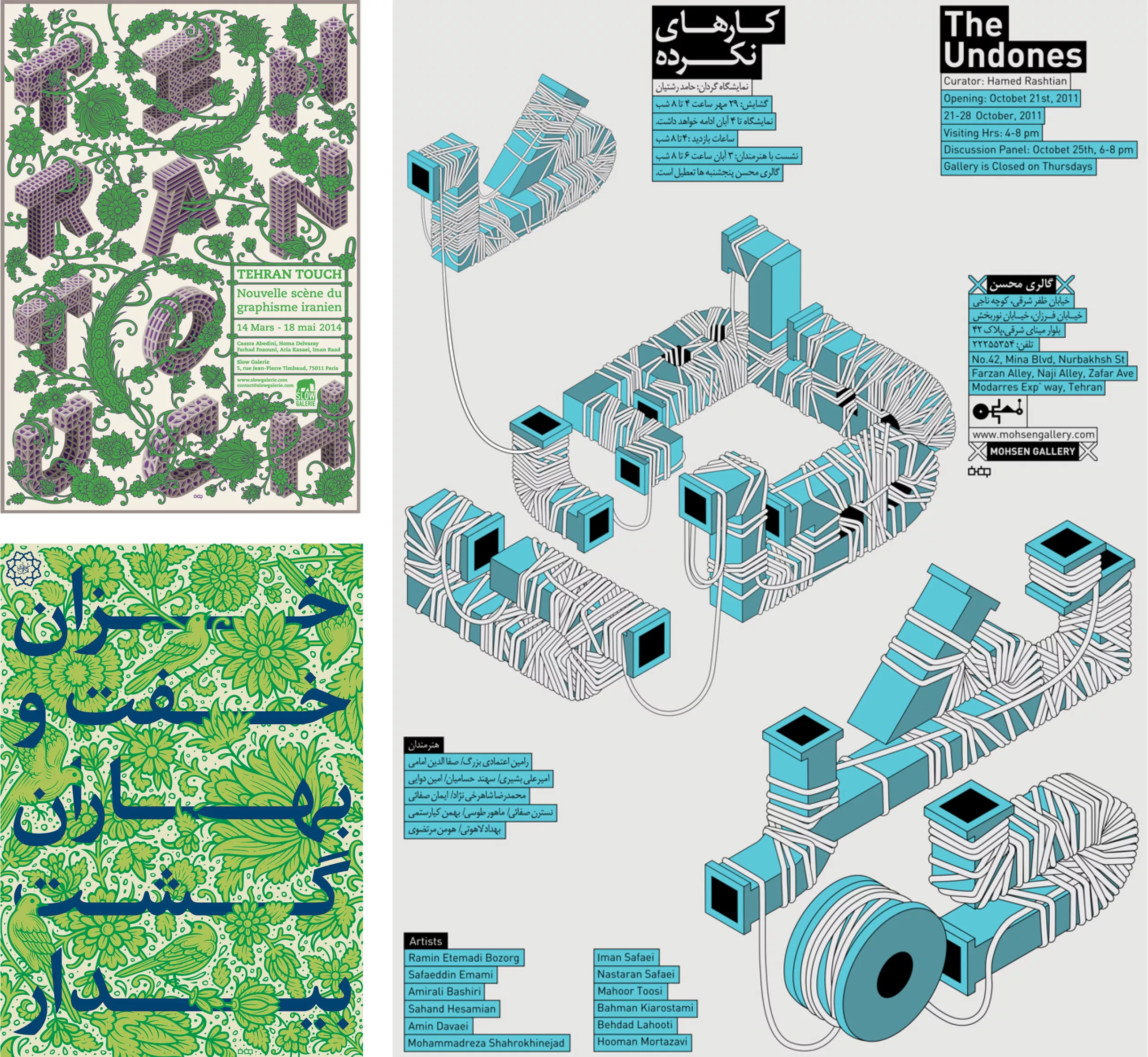

For if the context is a problem, the designer’s role is precisely to find a solution to the problems; whether they are erected by the client… or the government. Such conservative constraints then allow designers and artists to juggle with the limits of protest art. The post-revolution and post-war period, encompassing the years 90s-2000, heralds the birth of a new generation of graphic designers, in which designers seek to enhance their country’s heritage while creating a modern language.

Reza Abedini is the leading figure of this second movement. He teaches or has taught at Tehran’s Fine Arts, Azad University (the 4th largest in the world) and the Fine Arts section of Tehran University, thus training the third generation of Iranian designers. We have devoted a biography to him in our History of Graphic Design section which we invite you to discover.

It is important to note that the majority of the graphic achievements in Iran are related to the field of culture. As for the first generation of graphic designers, the other fields unfortunately show little interest in the matter.

The revival of Iranian graphic design

Iran’s immense cultural heritage is a strong force, and its bubbling youth continues to modernize and play with these traditions. “Iranian designers have the immense privilege of being born into a 3,000-year-old civilization. The sources of inspiration are almost inexhaustible, but this heritage sometimes tends to limit innovative ideas; it is a huge challenge to create something new that is shaped by so much history” explains graphic designer and illustrator Behrouz Hariri. The challenge today is to put the cursor in the right place.

With the rise of the Internet, Iranian designers have been able to enter into dialogue and exchange ideas and concepts with the rest of the world. In the same way, this openness has helped to show the true face of Iran: dynamic, cultured, curious and creative, which goes against the media. The young designers, born after the Islamic revolution, took pride in working in Farsi. Some unfortunately prefer to turn to the West and globalized standards in order to shine on the international scene. The older generation does not fail to remind them not to forget their roots.

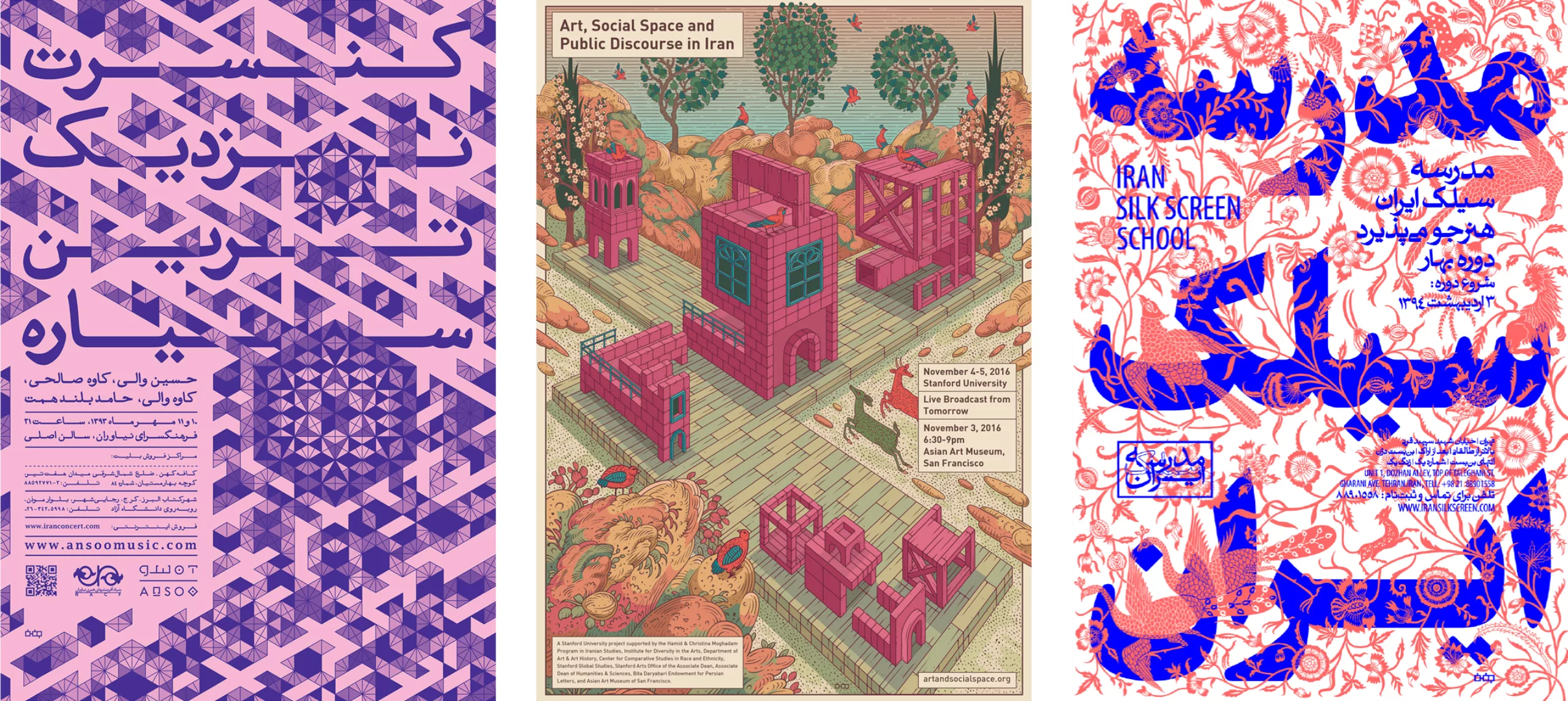

It is impossible to talk about the work of all the renowned graphic designers in Iran, but we have selected a few. To begin with, here is an overview of the work of three women graphic designers in Iran.

Homa Delvaray was a student of Reza Abedini. She lives and works in Iran, mostly on local artistic and cultural projects, but also receives commissions from clients in Europe and the United States. Her graphic work has been shown internationally and has been awarded many times. These first 6 posters were made around 2005…

…the next six, around 2015:

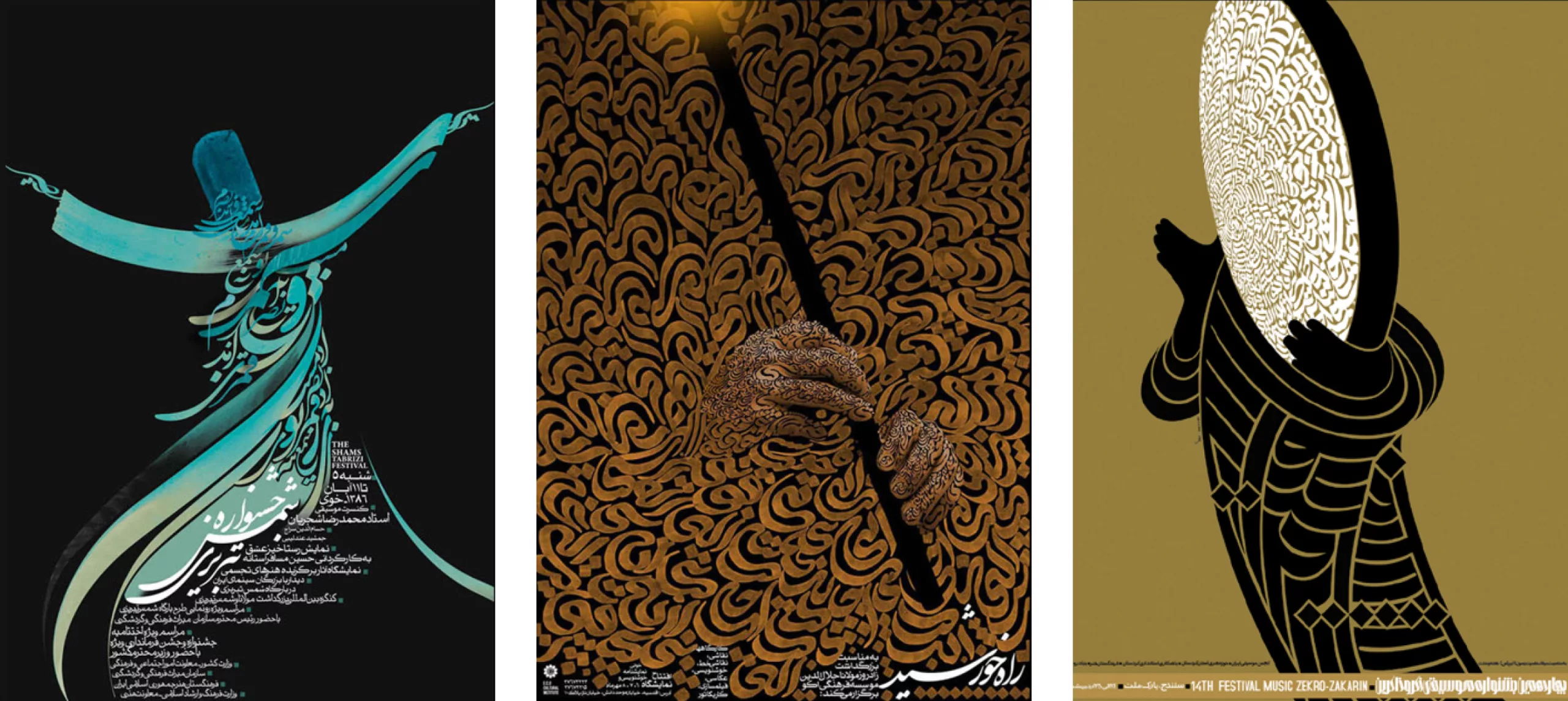

Zeynab Izadyar worked in Reza Abedini’s graphic design studio. She made these posters in 2007 for visual arts festivals.

She is now a clothing designer and launched her vvorkvvorkvvork brand in 2017 from the United States. She mixes artisanal techniques inherited from her country of origin (such as natural dyeing, calligraphy or Persian motifs) with a contemporary vision of clothing.

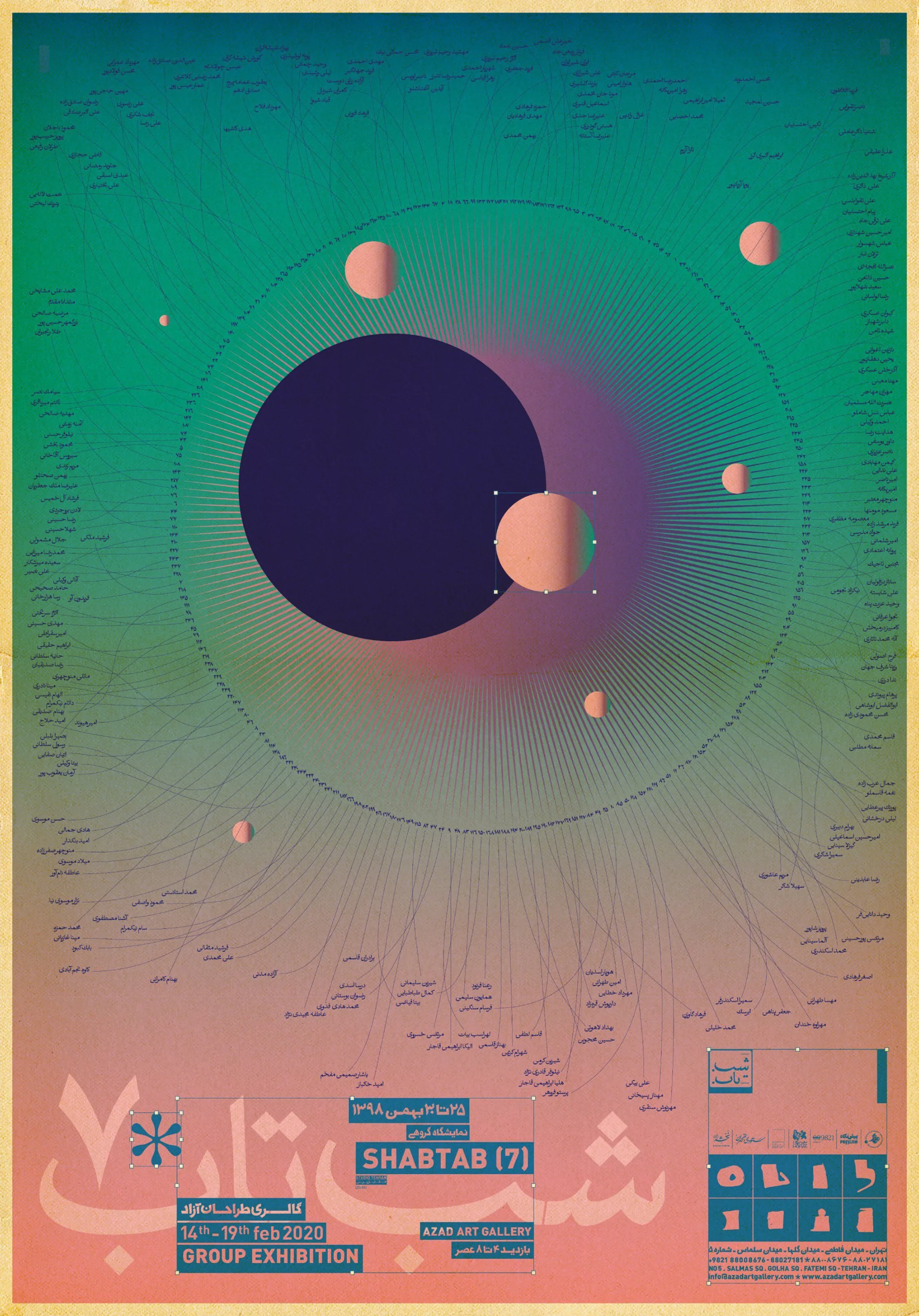

Other artists are grouped in studios, such as StudioTehran, which is very active on Instagram.

Aria Kasaei, founder of Studio Kargah, collaborated with Reza in setting up a series of posters to promote the Azad Gallery’s bi-weekly exhibitions. This project has helped to spread the influence of graphic design in Iran among public and private cultural organizations. It has had a huge impact on poster design in the Middle East and has enabled them to make their mark on the international graphic and art scene.

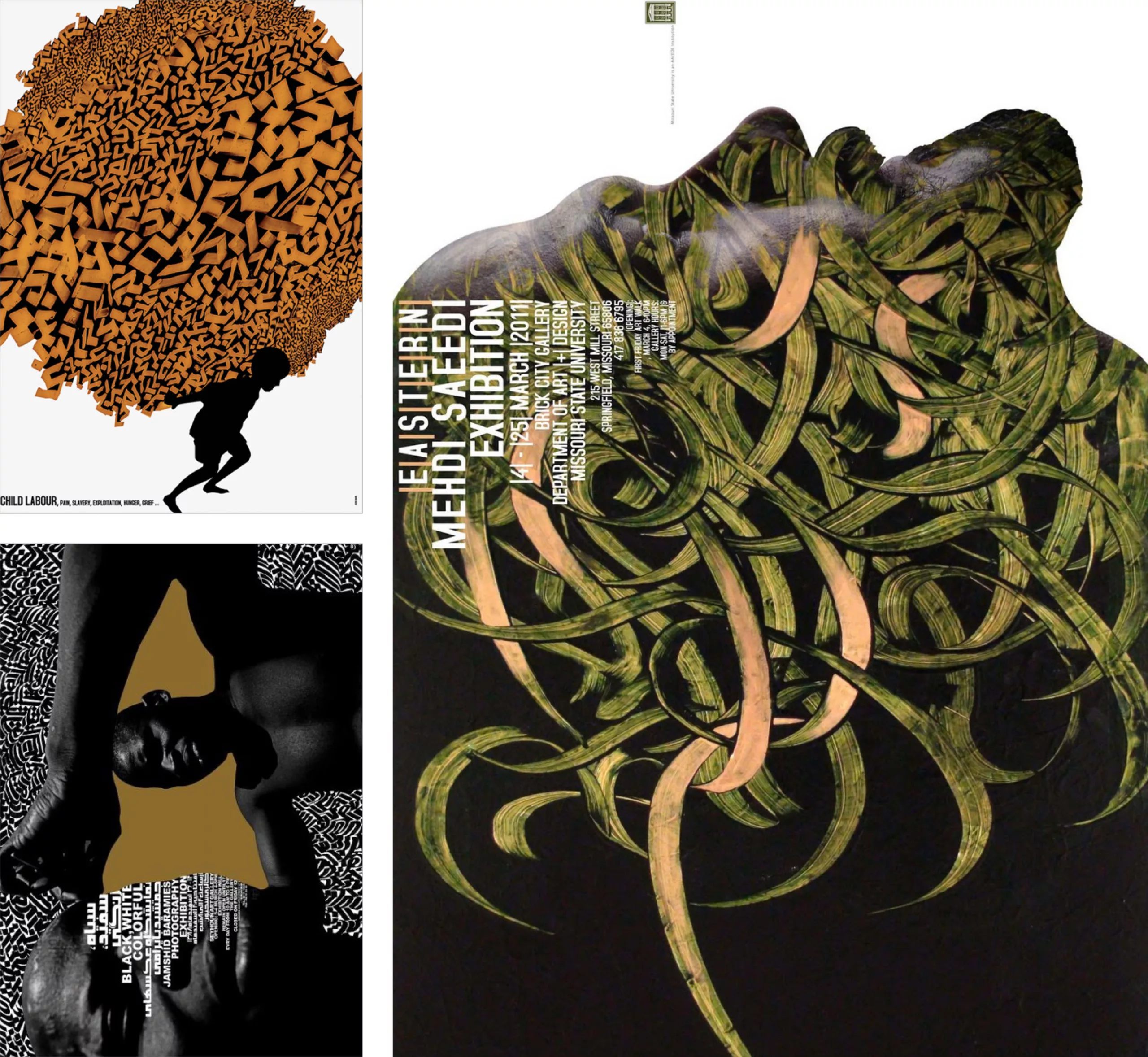

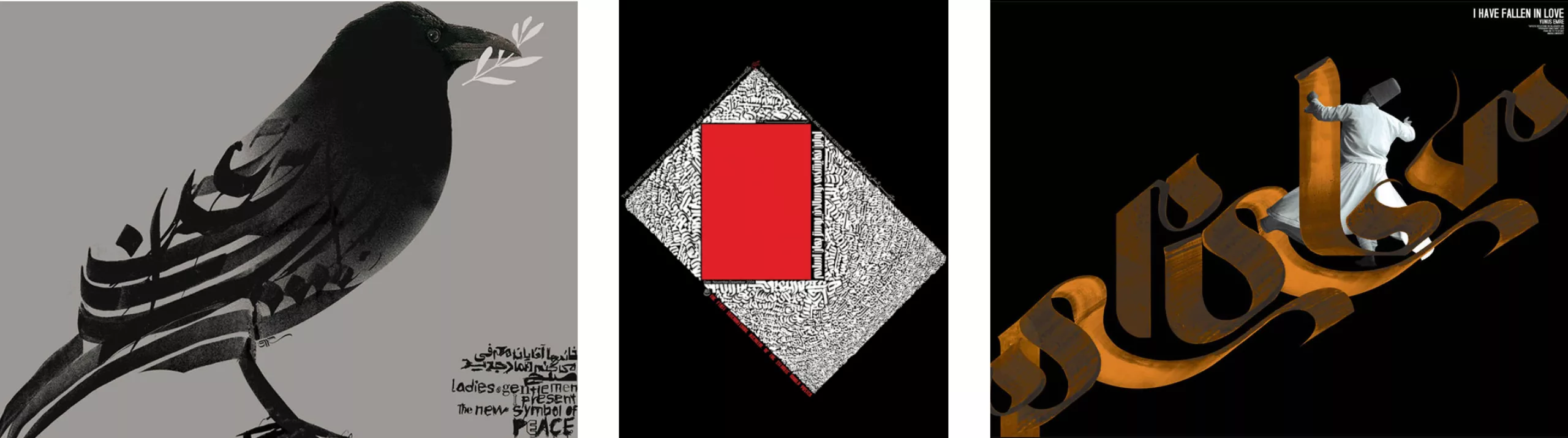

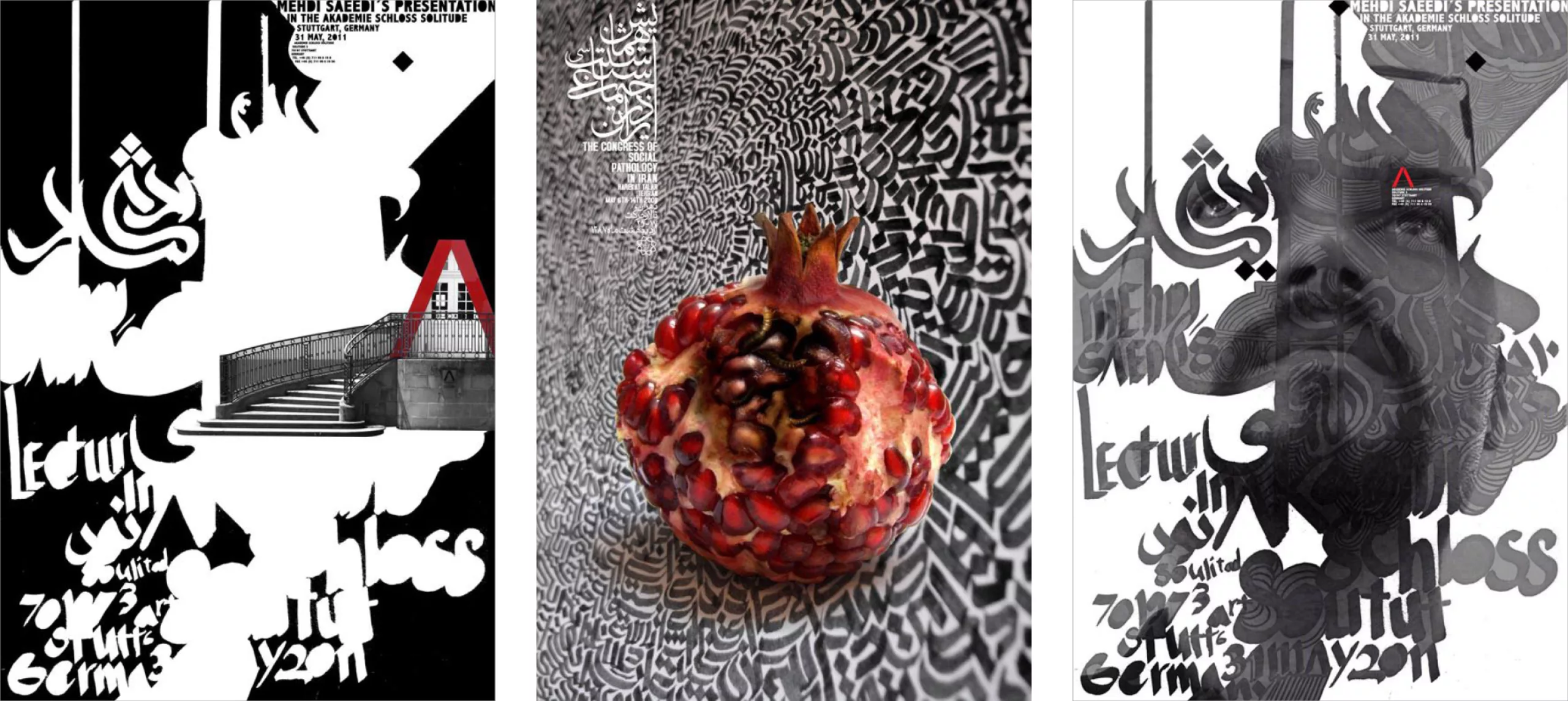

Mehdi Saeedi is also part of this new generation of prominent Iranian designers, although he now works in the United States. He helped develop the principles of calligraphy applied to typography, and is working on zoomorphism with Persian characters. In this sense, he has developed a course entitled “the melody of letters”.

To go further: There would be hundreds of other designers and artists to introduce you, but due to lack of space and an already well-stocked article, we invite you to discover Sina Fakour, Studio Melli, Masoud Morgan, Studio Metaphor, Mojtaba Adibi, Studio Tehran, Studio Kargah…

Geniuses come out of their lamps

One could logically believe that in such a context of censorship, graphic art – or art in general – would have difficulties to be born or to exist. And yet the opposite is true; art is a form of resistance, of memory, of duty. Muzzled by censorship but not paralyzed, like geniuses taken out of their lamps without being freed, artists and graphic designers cunningly perform in places kept secret until the last minute. Despite the wars and the political context, Iran is in the midst of change and offers an extremely fertile breeding ground for creation.

Tehran is home to many internationally renowned galleries and the Iranian art scene is far from being buried. Although the latter subsist without aid, sponsors, networks or foundations! Resourcefulness and mutual support between designer-geniuses reign supreme, and art market speculation – bracing and solid – is on the rise in this society with an uncertain economy. We can only continue to hope that graphic design and this creative energy will survive the current events, freeing its talents and creativity for good.

Some sources to go further:

- gdiran.blogspot.com

- www.telerama.fr

- Larousse : art et archéologie en Iran

- Larousse : Histoire de l’Iran

- Book : Arabesque, Graphic Design from the Arab World and Persia

Many thanks to Sina Fakour for proofreading and contacts!