Reza Abedini, father of iranian contemporary graphic design

Reza Abedini, graphic designer in Iran: a job, a legacy

To be a designer like Reza Abedini in a country like Iran is to carry within and recreate a 3000 years old extraordinary artistic, visual and calligraphic heritage. To follow the footsteps of an extremely rich history, that of an immense Empire that once became the artistic foundation of all surrounding civilizations. The kingdom of Persia has influenced not only Arab but also Western, Asian and African societies in the fields of architecture, sculpture, visual arts, writing and manual techniques.

Despite being torn apart by conquests, wars and enriched by various cultures, Iran has nevertheless distinguished itself from the Arab world developing its own language (Farsi) and culture, making it a singular country. As in other Muslim countries, it made great use of calligraphic art, of which arabesques and illuminations were used to sublimate the Koran, the sacred text.

Beaming on the world during antiquity, open to the West in the 1960s and then reclusive during the Islamic revolution of 1979, the country has gone through more or less favourable periods to visual expression. Despite the bad image conveyed in the media, Iran is nonetheless a high place of graphic design, recognized on the international scene, and full of talent.

Father of the post-revolutionary creation

Reza Abedini is the leading figure of the second generation of Iranian designers, post-Islamic Revolution (1979), from the 1990s onwards. Born in 1967, he trains, teaches and transmits his knowledge inherited from the first Iranian graphic designers who were trained in Fine Arts and Western graphic design, like Morteza Momayez before him. Far from creating in a closed-door environment, despite the political context, his work is recognized internationally, and seeks to perpetuate a Persian style and culture.

A member of the International Graphic Alliance and the Iranian Graphic Designer Society, he has been teaching at the Fine Arts Department of Tehran University (the 4th largest in the world) since 1996, in parallel with his work as a freelance graphic designer in the cultural field. In Iran, fine arts and graphic design are intimately linked. And because he is a renowned professor and graphic designer, the majority of contemporary Iranian graphic designers have been influenced and trained by Reza Abedini himself. He is thus THE leading figure of the post-revolution following Morteza Moyamez before him (figure of the pre-revolution).

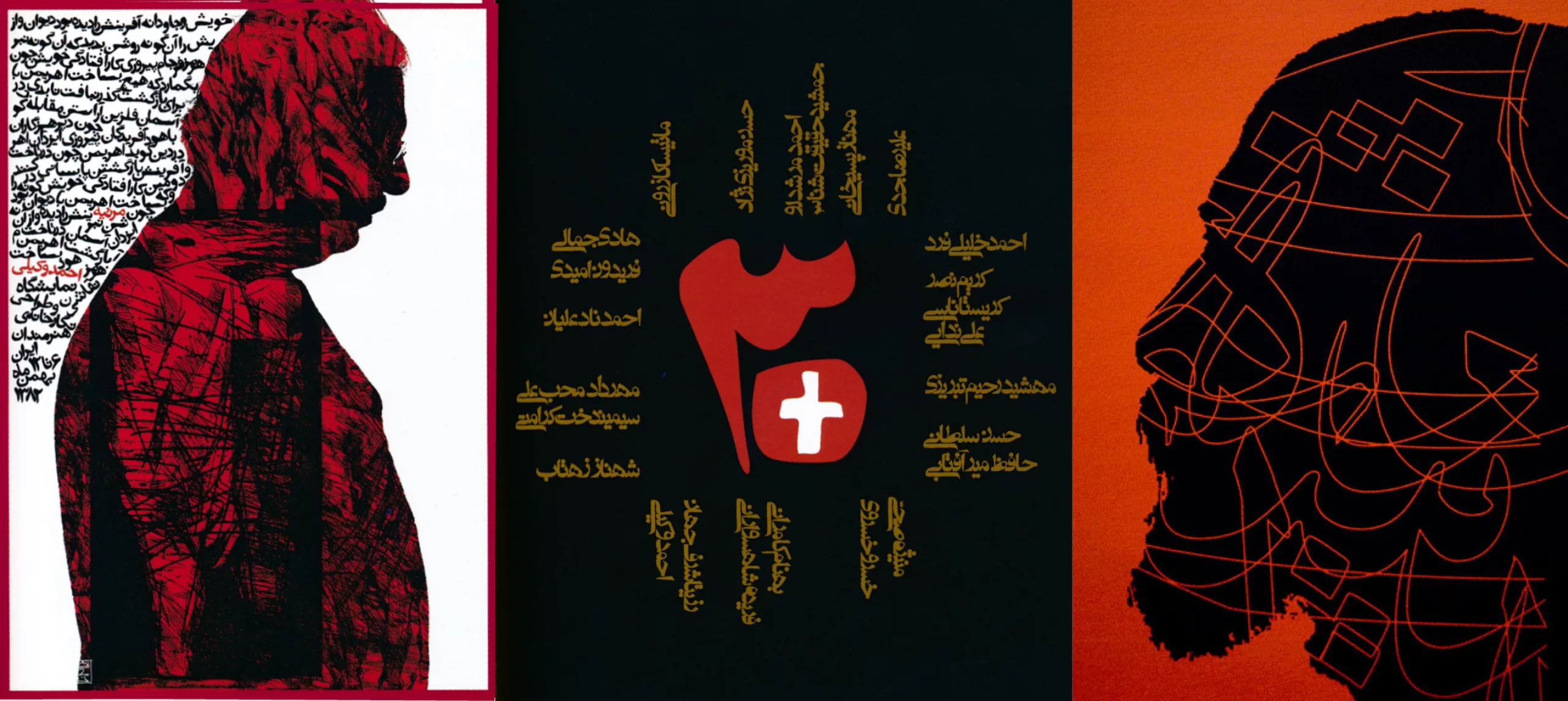

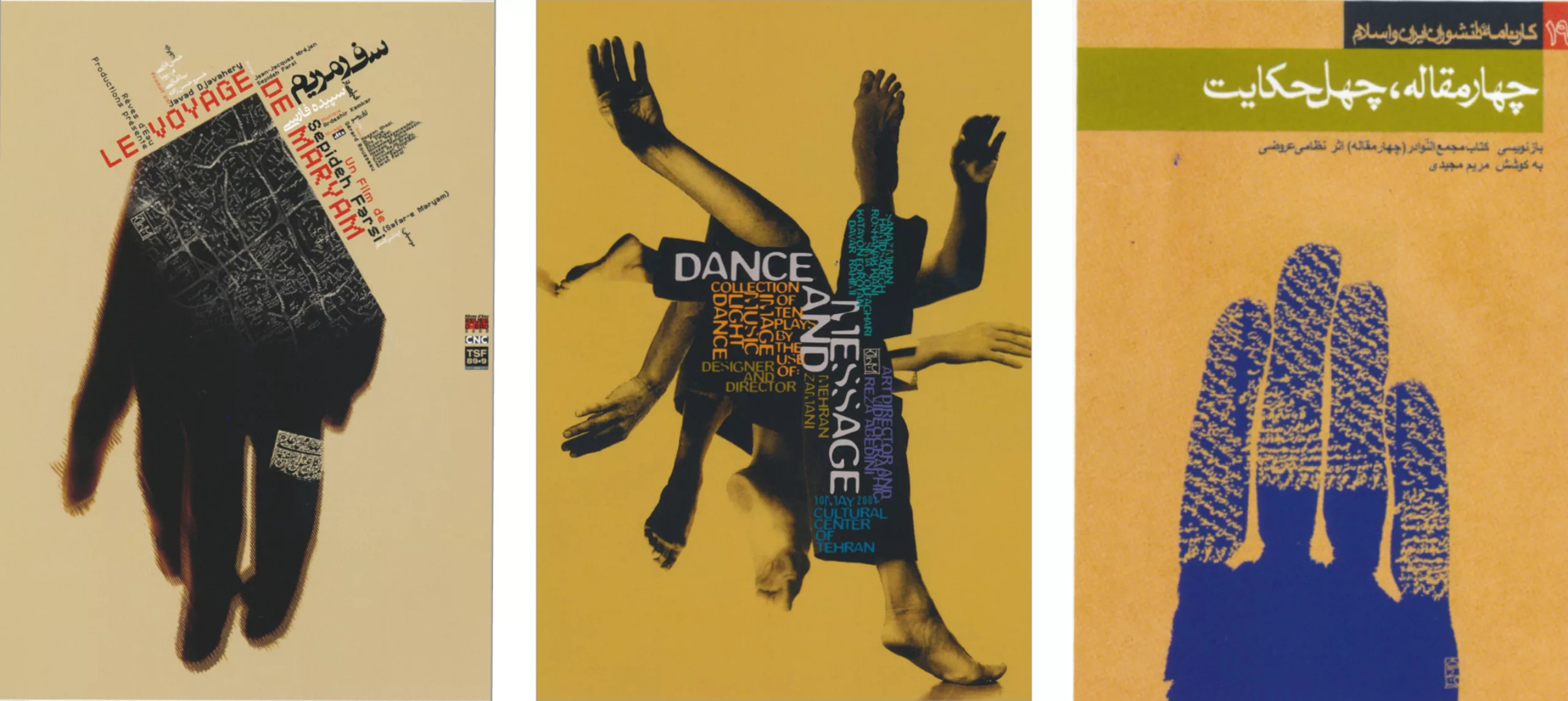

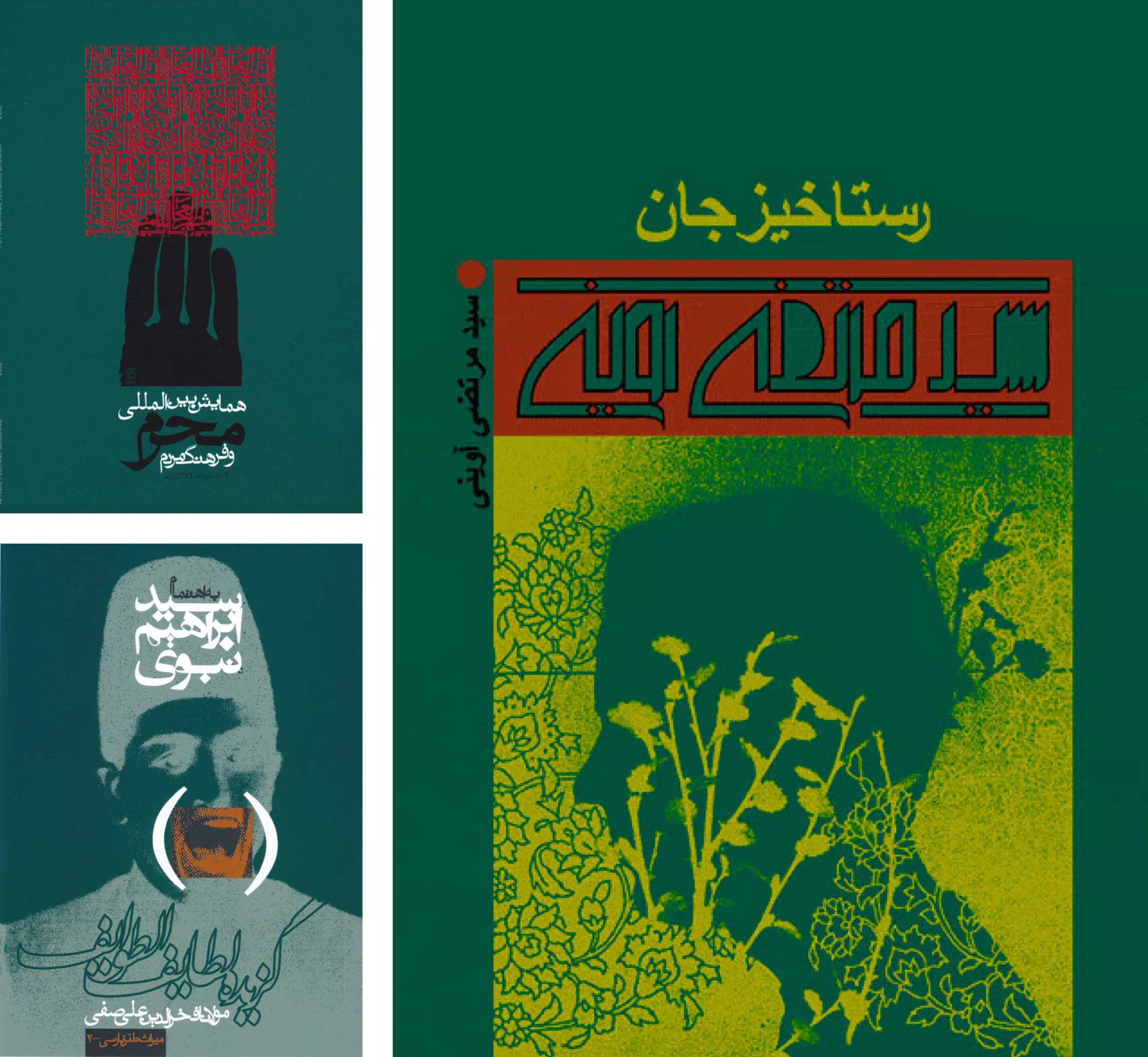

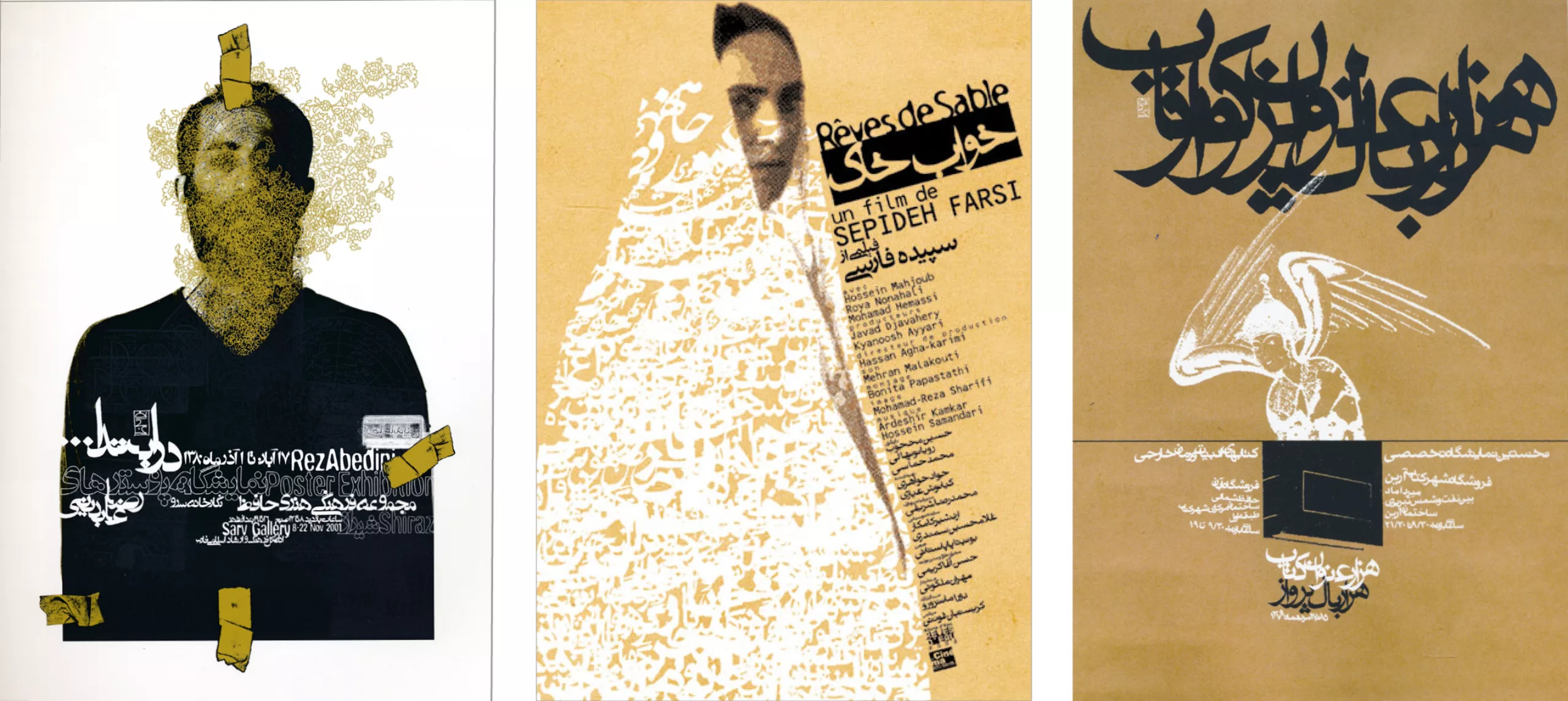

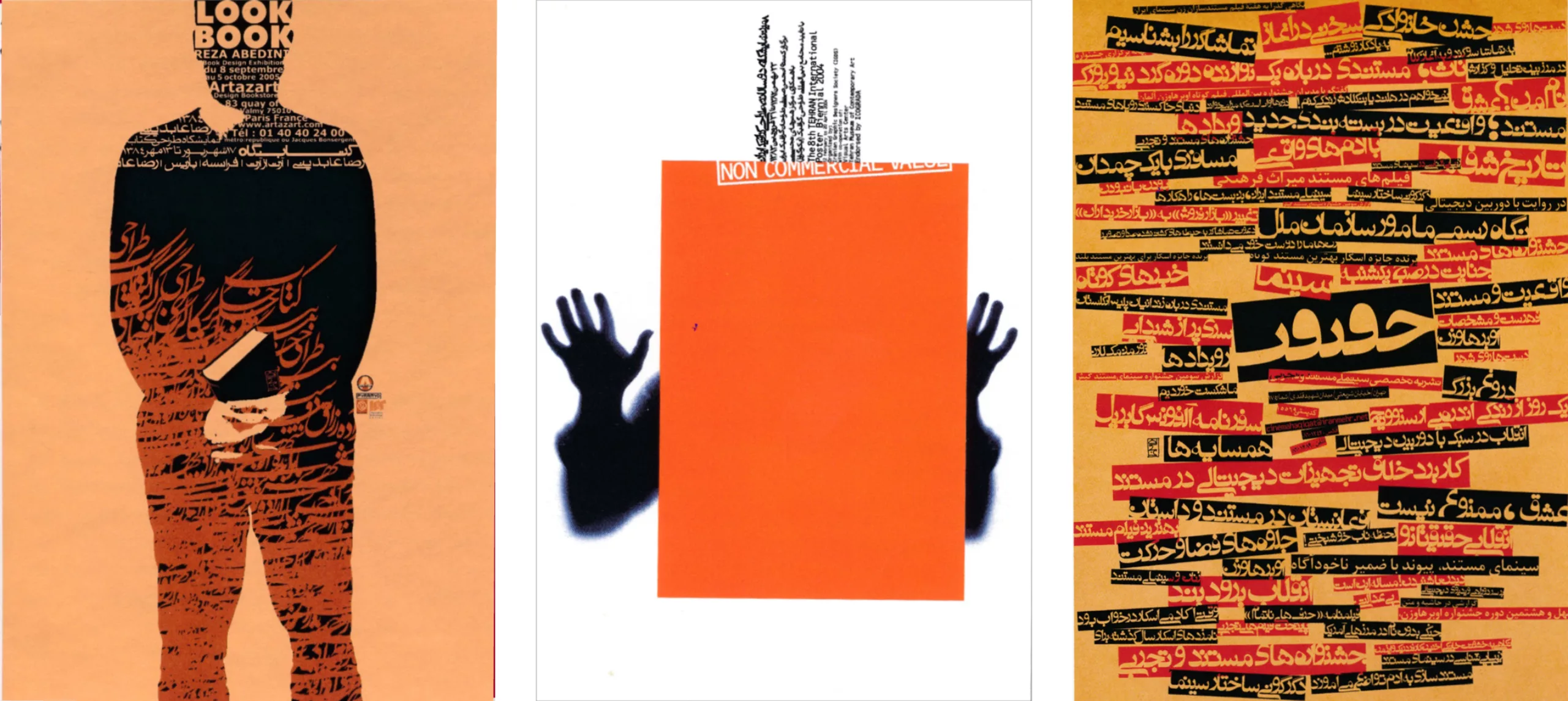

In perpetual research, “he gradually abandoned the inherited codes from the previous generation, to establish his own stylistic language elements. A style determined by the techniques and their limits, silkscreen printing, its large screens, and perhaps also its dull colours on tinted, kraft paper”, underlines Alain Le Quernec in the issue of design&designer (Pyramid editions) devoted to the Iranian graphic designer.

In this BBC excerpt that we have condensed, we can see Reza playing with letters as well as with pictures. Stylized handwritten lettering is indeed considered as a visual discipline and an image in its own. It has today a major place in all forms of Iranian artistic expression, which Reza Abedini was able to reinvent.

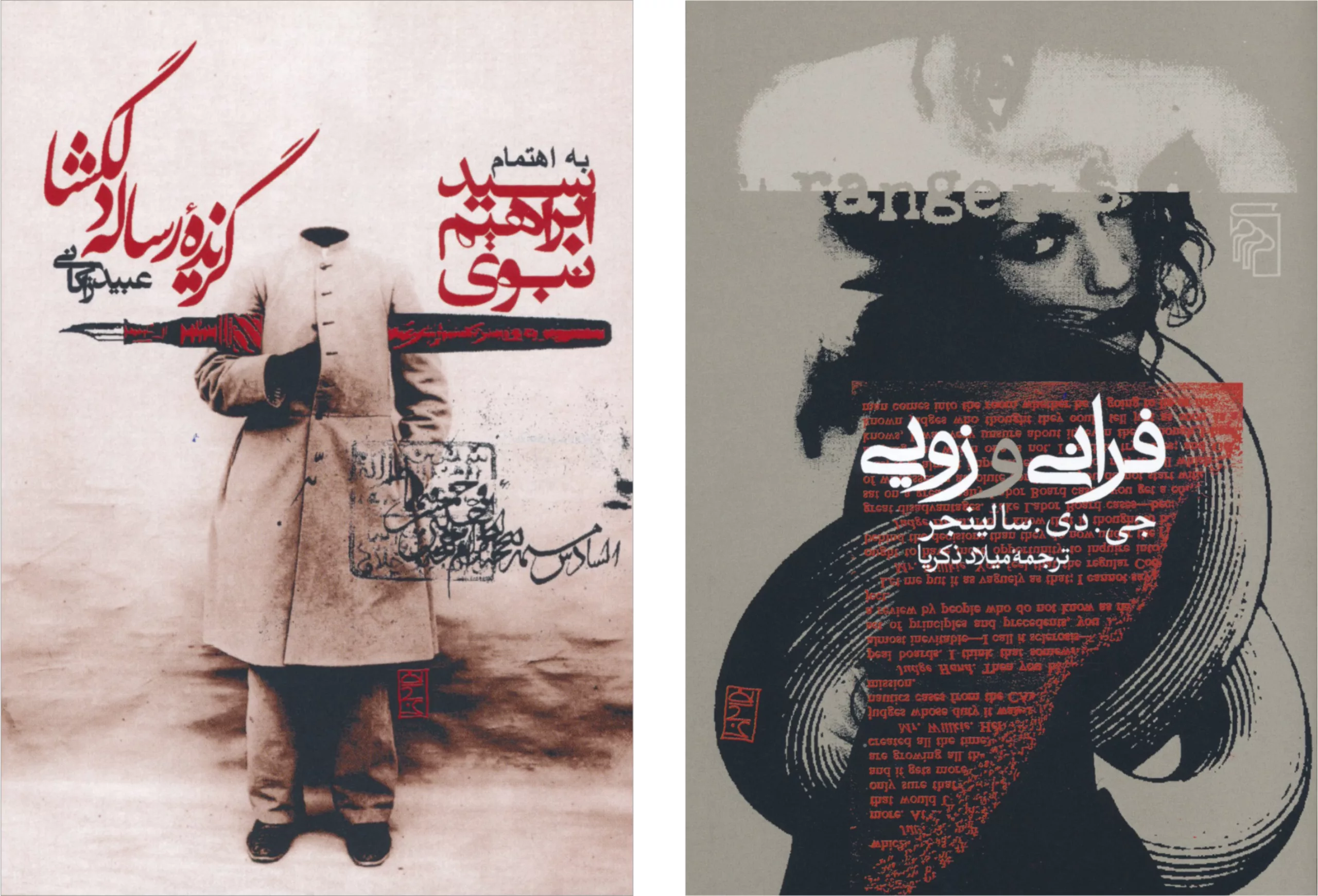

As we stated in our article on the genius of Iranian graphic design, “the art of calligraphy is still considered to be the most accomplished of the Applied Arts of Islam, and is widely used in Iranian graphic design. (…) It is a major element, even supplanting the visual (whereas it is mostly the opposite in our culture). Words and images intermingle to become one, letters become illustrations. One cannot grasp the meaning of Iranian graphic design without considering the importance of the text for this culture.”

Willing to assert a contemporary Persian graphic design, Reza Abedini is passionate about typography and Persian letters and draws fonts in Farsi alphabet. Without being purely calligraphic, his work is resolutely modern, while remaining in line with Iranian artistic codes. He thus mixes the codes of contemporary art and Persian calligraphy to create what he calls “persianity”. Indeed, it must be made clear that typography as we know it in the West has nothing to do with Iranian typography.

A typo-calli-graphic work: letters as images

In Western typefaces, typography gives energy to the letter; a meaning, a sensibility, an essence, from the designer to the user. The same sensitivity that was lost in the shift from hand to machine, from calligraphy to typography. However, due to their characteristic forms, Persian letters are imbued with an energy of their own, from which they are indissociable. They are almost always calligraphic, handmade. Before Reza Abedini, Farsi was not (or very rarely) digitized, and lithography was a very widely used medium for making posters or advertising supports, as these letters were almost impossible to type. Reza Abedini also asserts that “Iranian typography does not exist as such” (extract from Roshanak Keyghobadi’s essay What is Typography? January 2015). If we want to make a pun, we could then speak here of typo-calli-graphy, in its primary Greek sense: the art of writing beautiful graphic characters.

Persian typography design requires the designer to work hard to create not only letters but also multiple type combinations with each other, depending on their placement in the word. For, as in the Arabic language, letters merge to create new ones. The Iranian designer Sina Fakour, whom we met in Lyon and who shared with us some graphic resources about Iran, also completed his memoir on “Arabic writing, from manuscript to digital” (project 9/28). This typographical difficulty can be better understood with the image of Fakour’s work below, which shows that depending on its position in the word, the letter will be visually different (click on the image to enlarge).

Similarly here, Sina Fakour uses and rearranges the letters of the word “vote” to create new words: “yes” and “companionship”. A pun impossible to grasp in European culture, often seeing only the beauty of a folklore.

He gets this idea from this calligraphic heritage, just like Reza Abedini. The particularity of Persian typography, in contrast to Western typography, lies in the fact that it sublimates and combines this inherent energy and brings its aesthetic criteria to life, as Saed Meshki explains in his essay “What is typography?“. (what is typography) (2004).

It is almost impossible for us to grasp all its nuances and references, but we can nevertheless appreciate its composition, colours, patterns and arabesques.

Reza Abedini’s work has been rewarded many times, notably for the best film poster in Iran, or at the Chaumont poster festival. He has also received awards at poster biennials in Mexico, Iran, Hong Kong…

If you want to learn more about Iranian design, its origins and current representations, we recommend you to read our article on the genius of Iranian graphic design!