Anni Albers, weaving Bauhaus and modernity

Annelise Else Frieda Fleischmann (1899-1994) was a German art theorist, textile designer, jeweller and lithographer. A young, cultured middle-class girl with a passion for art, the woman better known as Anni Albers was one of the few women from the Bauhaus school to achieve fame during her lifetime (her husband received much more media coverage) and the first textile artist to have a solo exhibition at MoMa in New York. Her work dusted off and modernised tapestry and textile art.

You’ll be a weaver, my daughter

Trained as a painter by private tutors, Annelise went on to enter the Bauhaus (the “house of construction”) in the 1920s, insisting on doing so after being turned down for the entrance exam. Josef Albers, her future husband, was on the jury as a teacher. The German school is progressive and revolutionary in the way it reconciles art and craft, links form and function, and deals with modern and classical raw materials, and the technical workshops are open (in theory) to everyone.

The Bauhaus school was intended to be emancipatory: director Walter Gropius included equality between women and men in his manifesto, so that they would be treated in the same way as men, without discrimination – a rare occurrence at the time, but one that deserves to be highlighted. In the first year of the Bauhaus, more women than men attended the school, motivated by the desire to move away from literature and art history and towards more manual occupations.

However, in order to avoid making waves in this patriarchal environment and to continue to receive government subsidies, Gropius gradually tightened the criteria for the jury to admit women to the school (this was probably the reason for Annelise’s first failure) and then systematically directed them towards the textile workshop, which was said to be more “naturally” feminine. , “for their own good and for that of the school” as Gropius put it: it was believed that they thought in 2D only, and not in 3D unlike men…

Anni souhaite explorer la conception et la fabrication dans différents domaines, et s’intéresse au verre, au bois, à la peinture, au métal et à la fresque murale. Si elle s’essaye aux autres ateliers, elle ne peut cependant pas s’adonner à la fresque à cause d’une maladie nerveuse qui la fait boiter et l’empêche de monter aux échelles. Annelise joined the Bauhaus weaving workshop reluctantly and because she was urged to do so, but she soon realised that the school offered training that was a far cry from the simple “ladies’ embroidery” practised in the private and domestic sphere or in other schools.

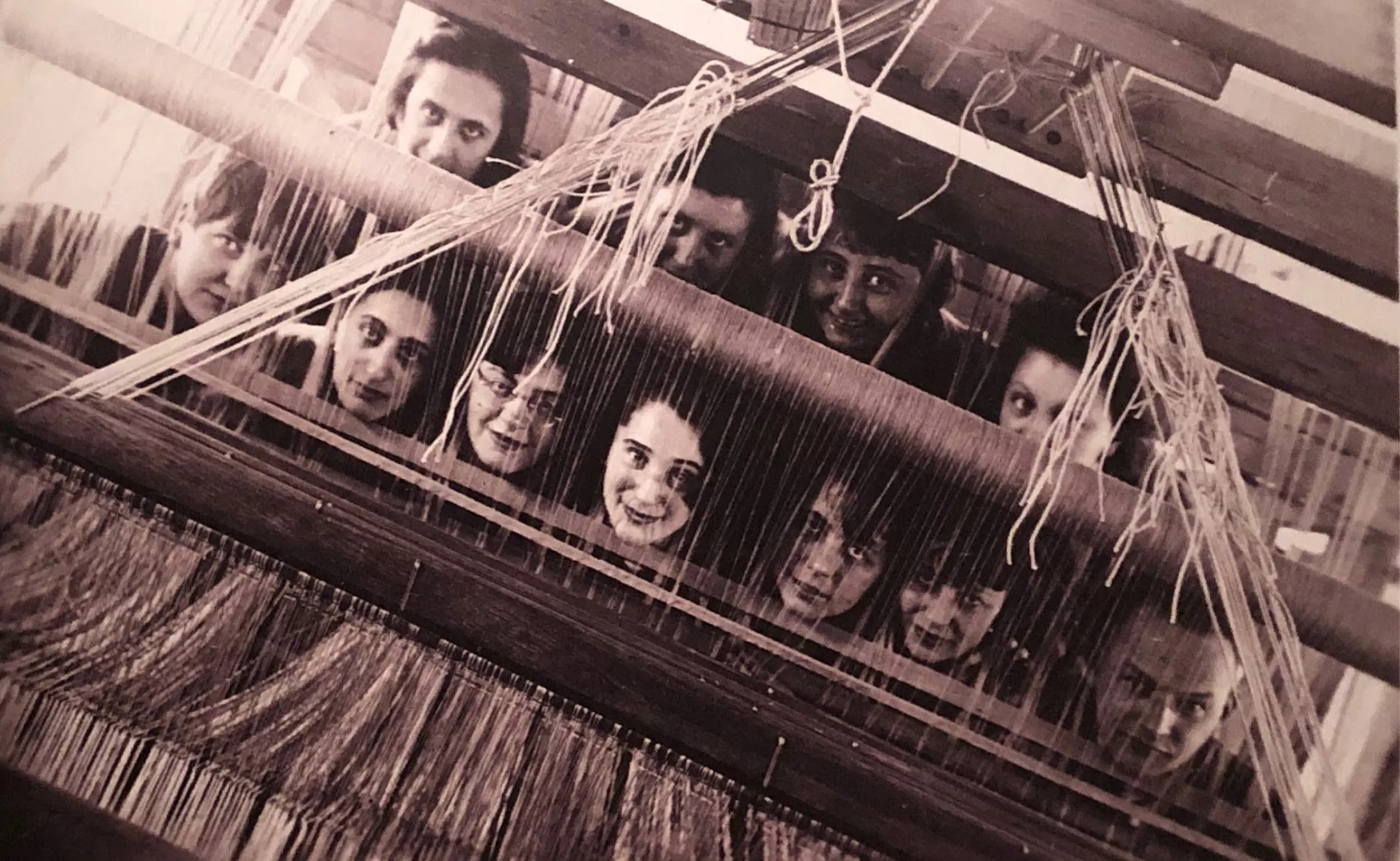

The Bauhaus textile workshop, a world of possibilities

During the Renaissance, weaving was considered to be the noblest of the arts, practised by men. “During the Renaissance, Raphael was paid five times more for the tapestries he designed to adorn the walls of the Sistine Chapel than Michelangelo was for the ceiling fresco”, explains Janis Jefferies, a researcher specialising in textiles. For a long time reserved for women and devalued, the practice of the loom or needle was dusted off and brought back into fashion by the British William Morris, founder of the arts and crafts movement, which aimed to enhance the value of craft work, then threatened by the industrial revolution. The Bauhaus school took up the baton in Germany, also aiming to blur hierarchies and bring low-cost art into everyday life.

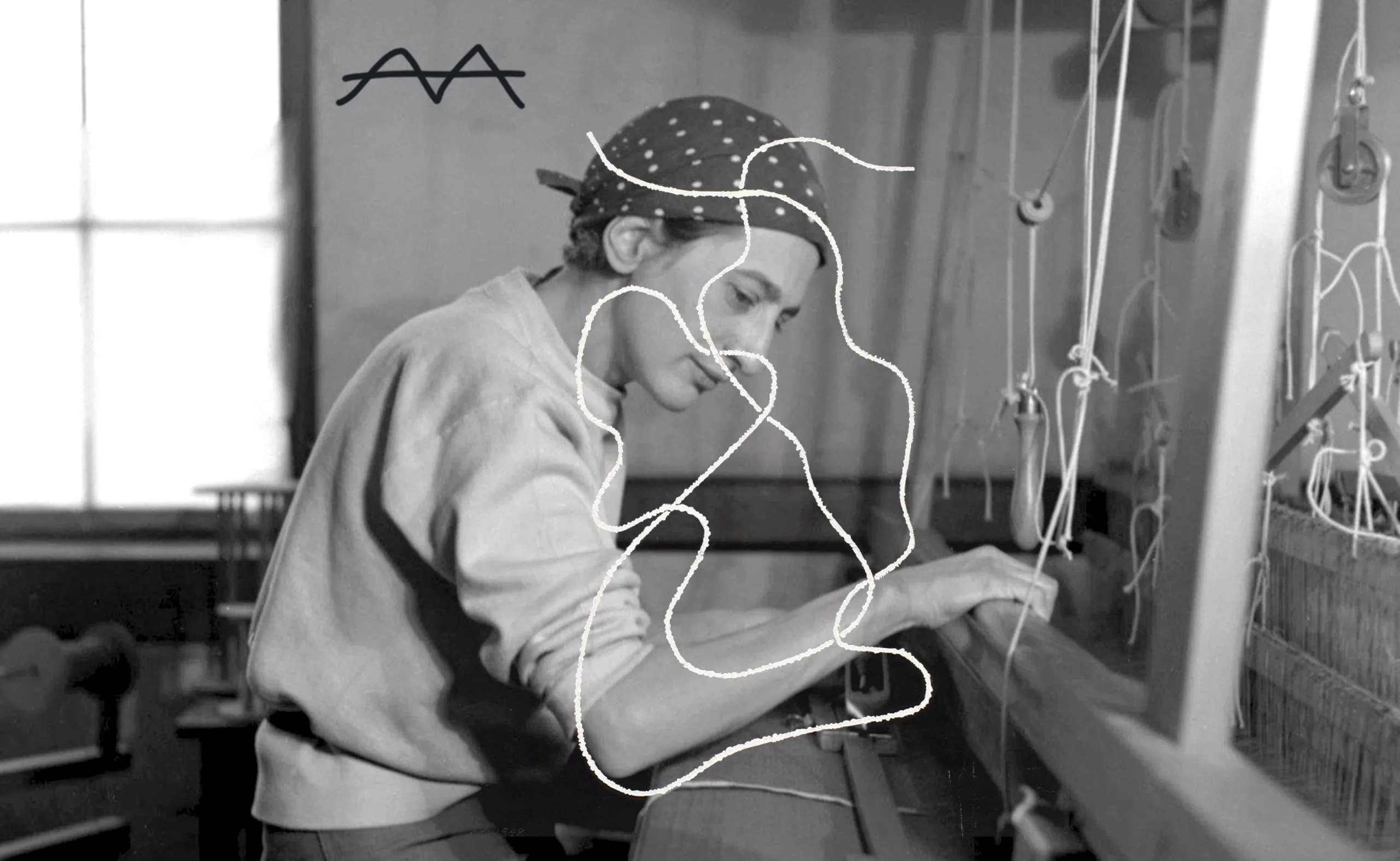

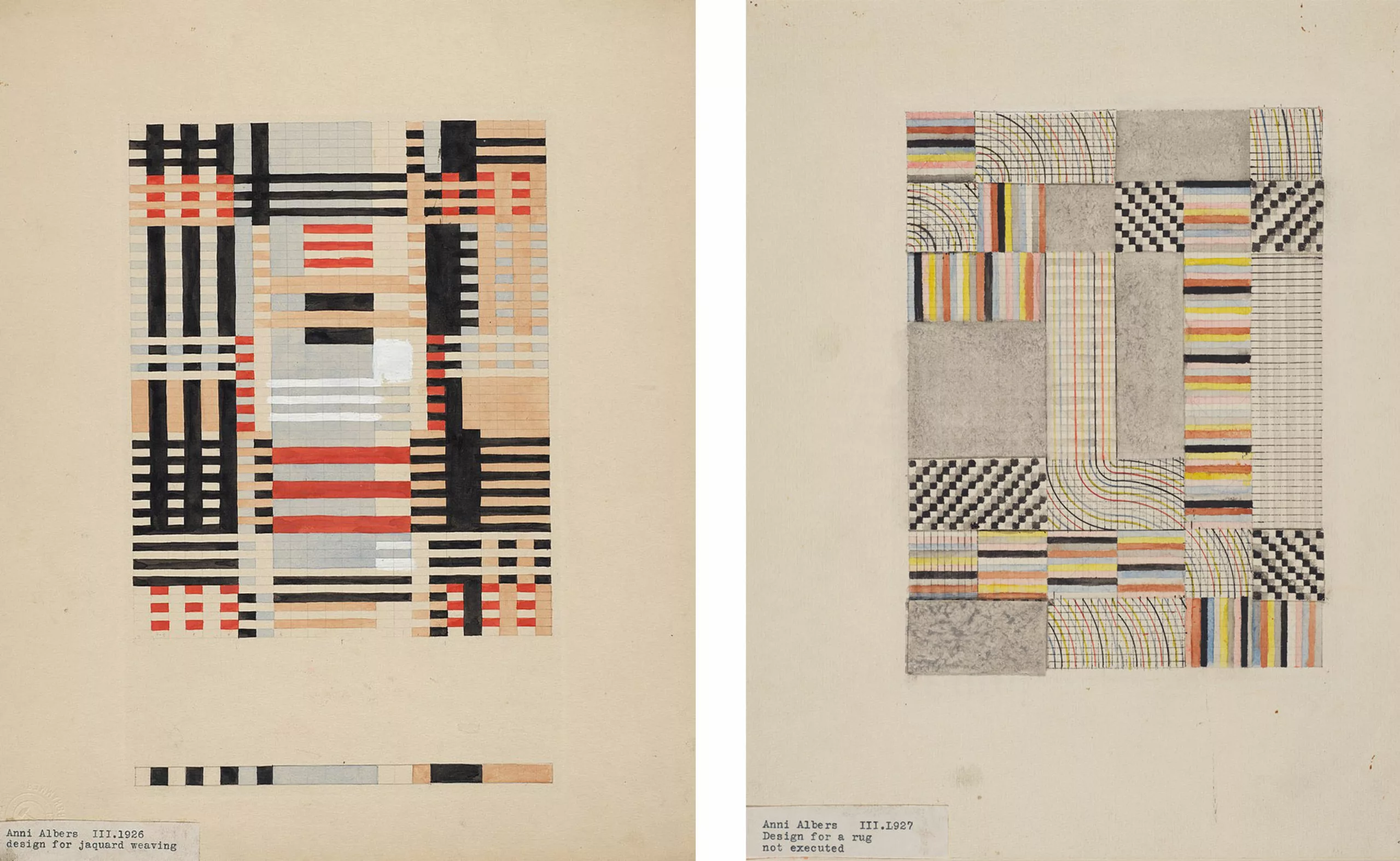

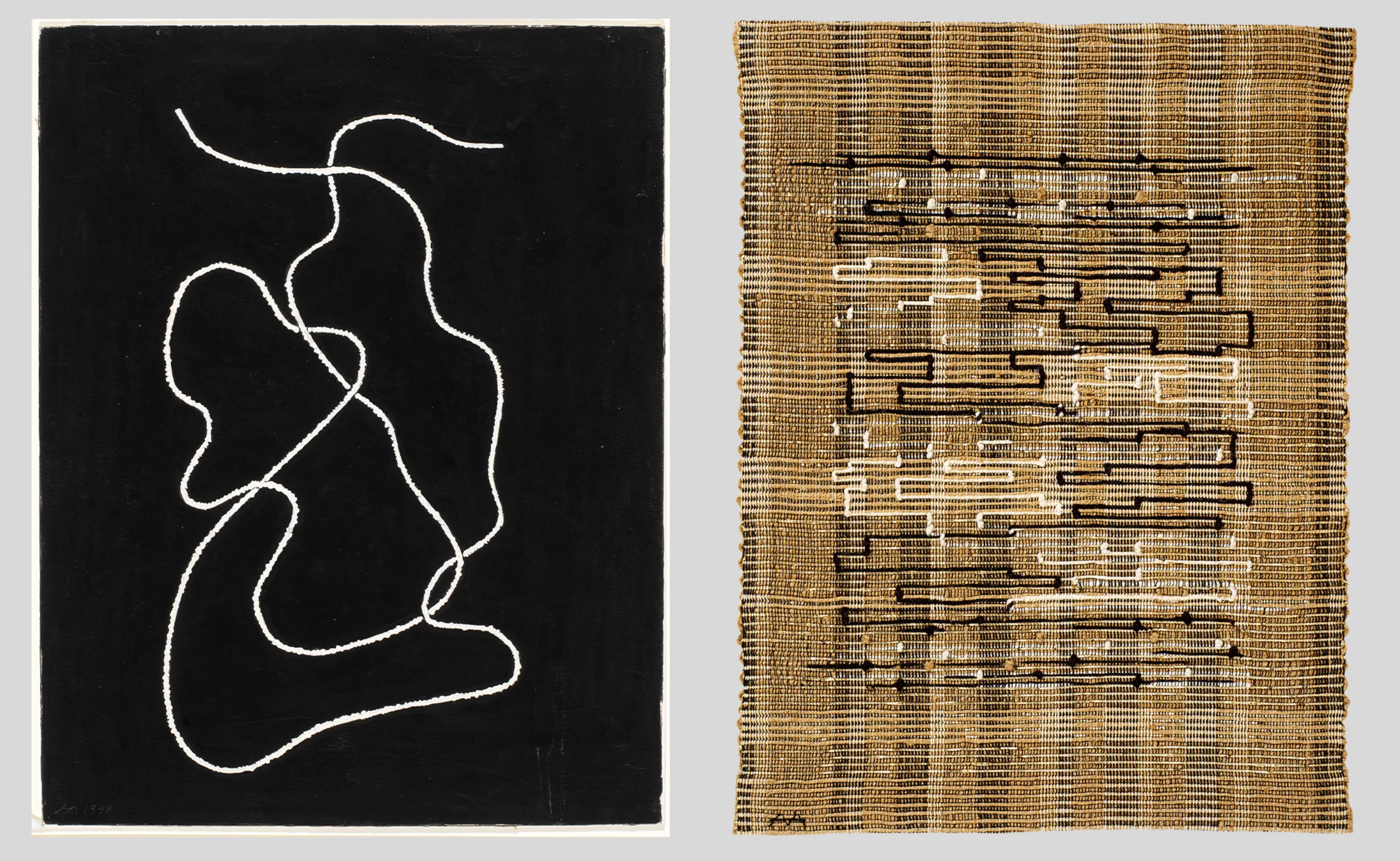

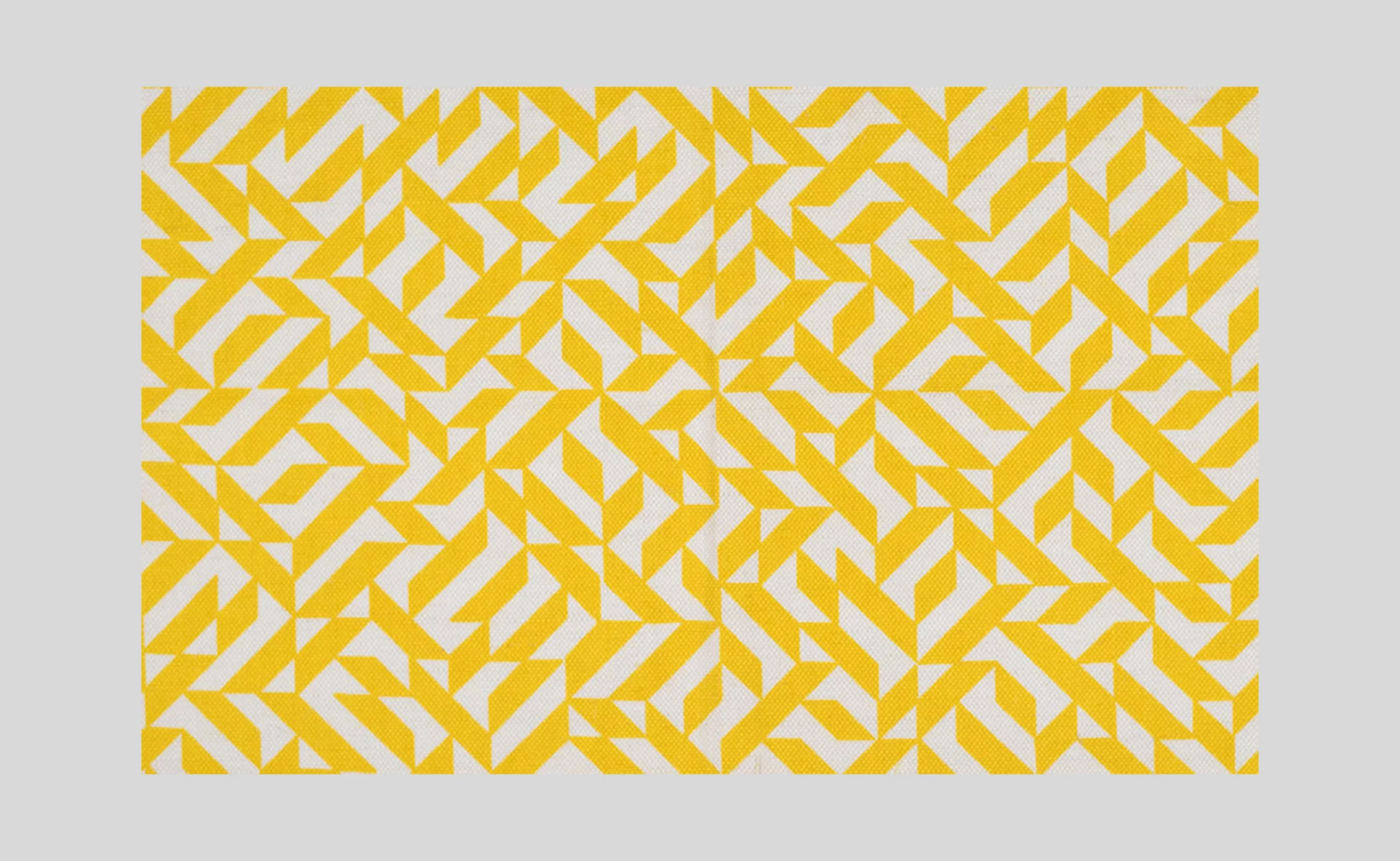

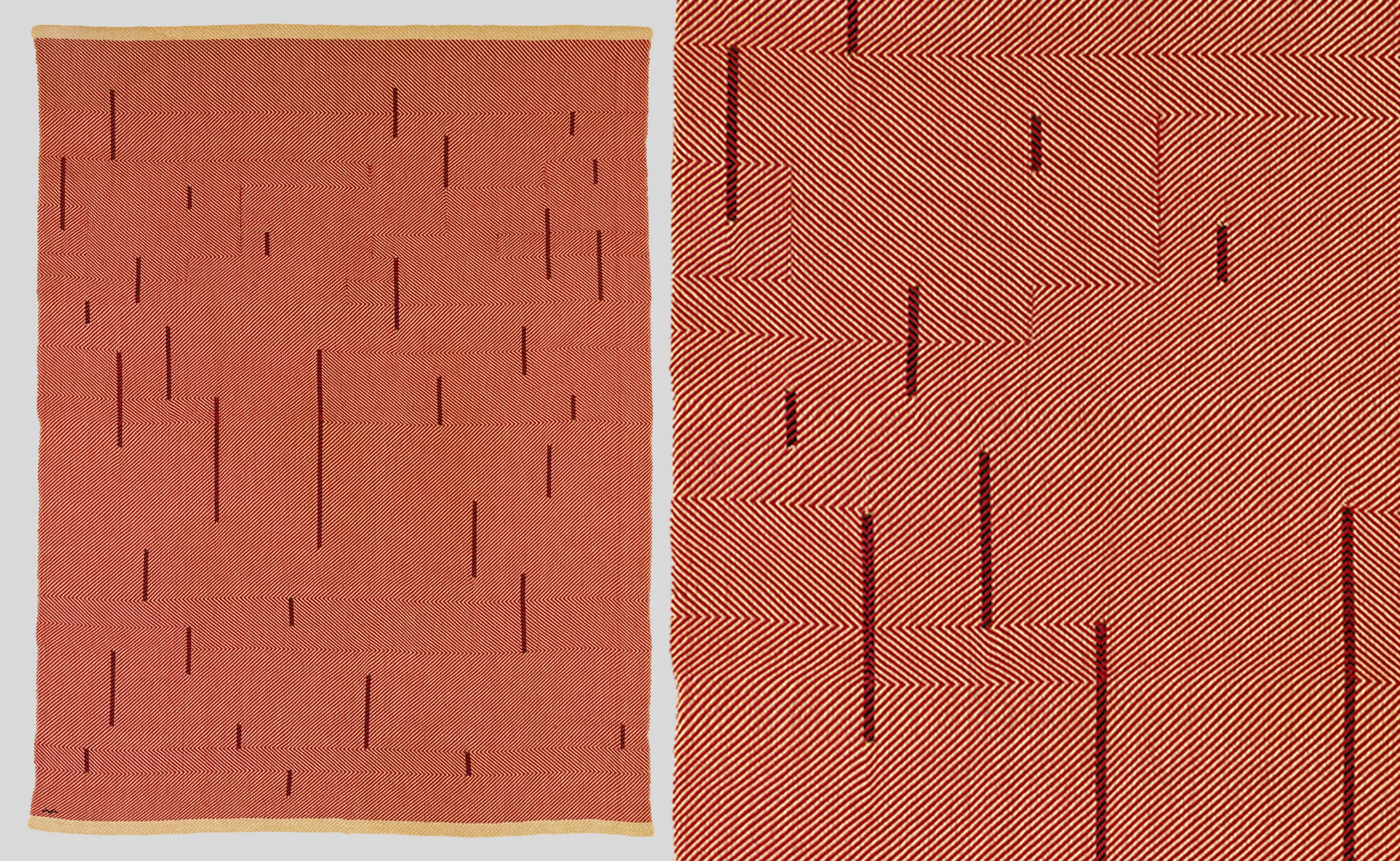

This opened up a world of possibilities for Anni, in which she could play with the number of threads, materials and colours, and produce in series. She studied with renowned master artists such as Paul Klee, Georg Muche and Johannes Itten, who taught her to master composition, colour and space. She also studied under and worked with Gunta Stölzl, the famous weaver, when the school moved to Dessau in 1925. Stölzl was the first female ‘master’ of the Bauhaus (a term used in reference to medieval guilds), who taught alongside Gropius, Bayer, Breuer, Kandinsky and Klee, among others… Josef Albers was also a student who attained the status of master. An explorer and jack-of-all-trades, Anni quickly became interested in a variety of yarn materials and techniques, creating different types of interlacing or knots using a weaving process that had remained unchanged since its invention. She also invented abstract or geometric motifs inspired by Russian constructivism, and tried her hand at relief, for example.

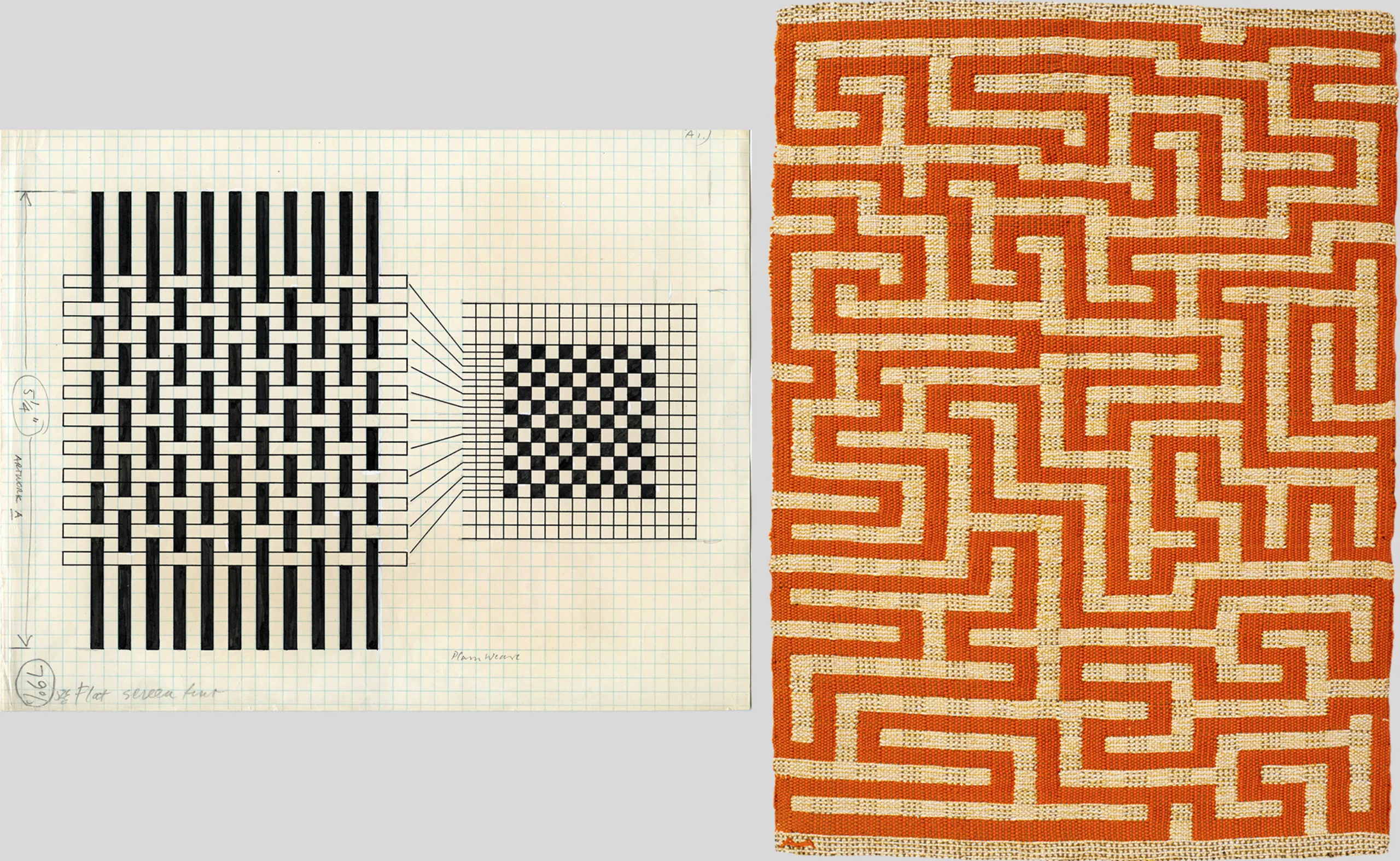

Unlike painting, where the gesture is free, weaving is constrained by the structural ‘grid’ of the loom, whose various rules enable a pattern to be created or developed by interweaving threads. The creation of a pattern is called a “weave”, which conveys the idea of rigidity rather than flexibility. Through her art and her ability to create under constraint, Anni reveals in her early work the structure of weaving itself, without trying to make sense of it, but rather to show it. Inspired by the Vienna School, like Otto Neurath, one of the founders of Isotype, she would say: “the thing itself is the meaning”.

Anni & Josef Albers, an inspiring couple

At the Bauhaus, Anni met Josef. They both experimented with art and techniques without limiting themselves, taking an interest in forms… before forging stronger links. Anni’s early works explored interweaving natural and artificial fibres, and Josef’s glass and metal, before specialising in painting. Annelise married the painter Josef Albers in 1925, one of the “Bauhaus masters”, who ran the glass workshop. Pioneers of twentieth-century modernism, the couple created both jointly and separately, and were interested in geometric form, colour and different techniques. Both “think with their eyes”, as Josef puts it. Their work jointly explores the principles of Bauhaus and modernism: geometric composition, new modern materials, compositional grids, etc. The two artists pursued separate careers, combining their research and inspirations, but not their art.

Anni Albers graduated in 1930. She took charge of the weaving workshop at the new Bauhaus school in Dessau, for which Gropius commissioned her to make hangings for the “master house”. Like many other Bauhaus artists and teachers, Anni (who is Jewish) and Josef emigrated to the United States in 1933 when the school closed (banned and closed by the Nazi party, which saw it as a concentration of “degenerate art”) to avoid persecution.

America, from Eden to pre-Columbian art

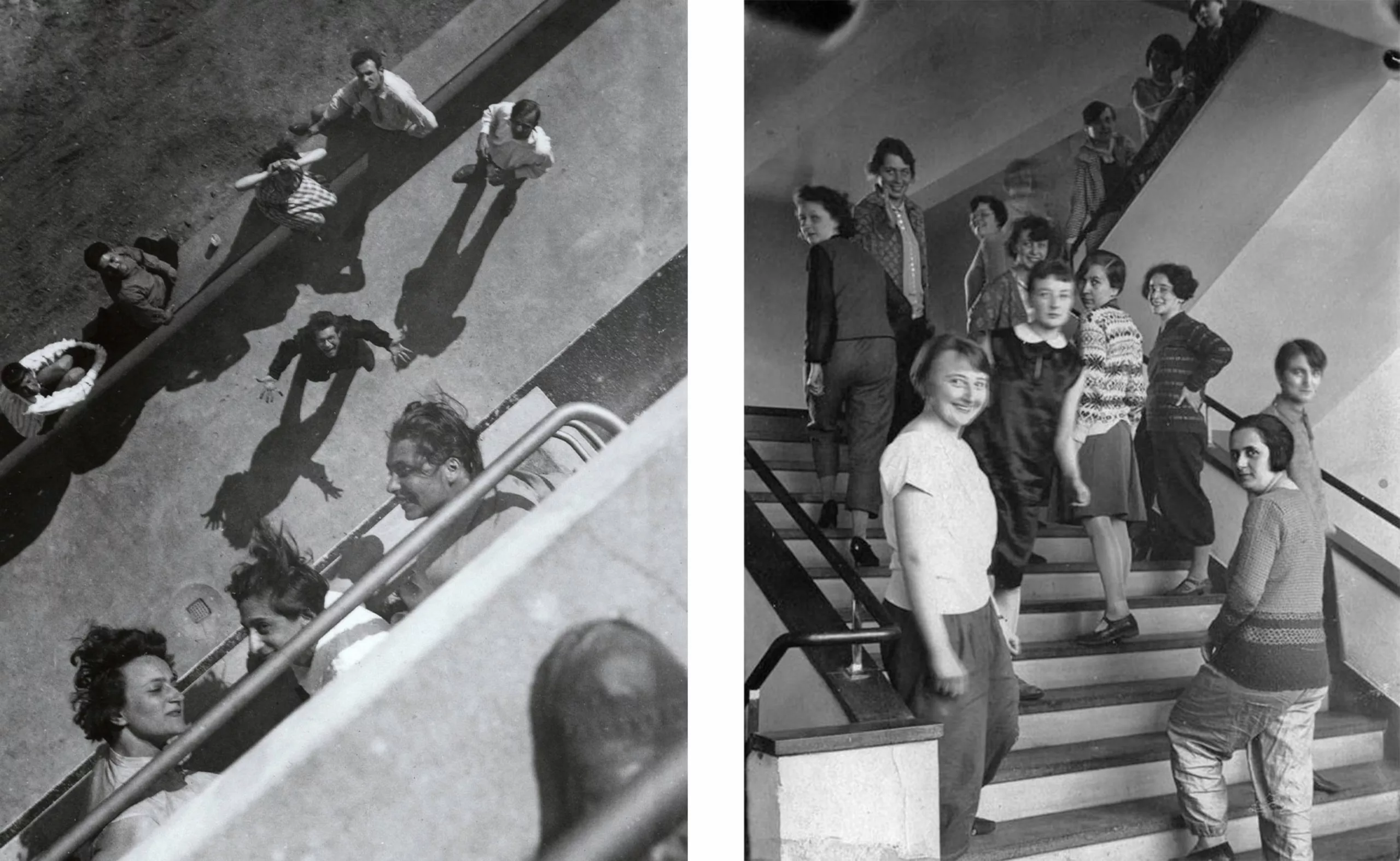

In the United States, the two artists were invited to teach at Black Mountain College, a new founding and avant-garde institution of American art, which differed in every way from the local classical universities and resembled a Bauhaus on the other side of the Atlantic. Anni and Josef in turn invited an ‘old hand’ of the Bauhaus, the architect and first director Walter Gropius. The modern building is set in the middle of nature on the banks of Lake Eden, and invites renowned teachers and equally remarkable students to experiment, exchange and create together. The educational project nurtures an autonomous community to which everyone contributes through agricultural work and involvement in collective and manual tasks. Anni, who is in charge of textiles, will continue throughout her career to develop new techniques by integrating modern materials into her creations. Josef developed a theory and practice around perception, and was interested in the neutrality of black and white. He taught Robert Rauschenberg (who created the first happening at a summer camp) and John Cage, among others.

American citizens since 1939, Anni & Josef’s passion for pre-Columbian and Mexican cultures led them to make fifteen trips to Latin America. From mass-produced Chupicuaro statuettes, to Inca wall designs, Navajo geometric carpets and Diego Rivera frescoes, their motifs and art were transformed. Inspired, Anni moved away from the modernist, functional rigor of the Bauhaus, adding diagonals, triangles or loops, more complex patterns and textures, more vibrant and dissonant colors… all the while seeking the timelessness of early forms of writing and construction. It was at this time that Anni Albers lent herself to more fantasies, letting more organic motifs and forms into her compositions, touched by the craftsmanship of this “promised land of abstract art” as Josef describes it, among the “great masters of Peru”. Josef, for his part, was unperturbed by repetition, fascinated by the motif of the square, which he repeated in monochrome duets in over 2,000 canvases over 26 years…

Returning to the original spirit of the Bauhaus, which encouraged the weaving of links between art and technology, between the hand and industrial technique, Anni Albers constantly explores and creates from synthetic and natural materials such as rayon, silver wire, wool or cellophane. She also has fun decompartmentalizing jewelry, creating astonishing ornaments from everyday objects such as paper clips, safety pins and colanders. Recognized as an artist, she exhibited her textile work at New York’s MoMA in 1949, having always collaborated, but never being totally eclipsed by her husband’s talent.

Pictorial weavings, hybrids between text and textile

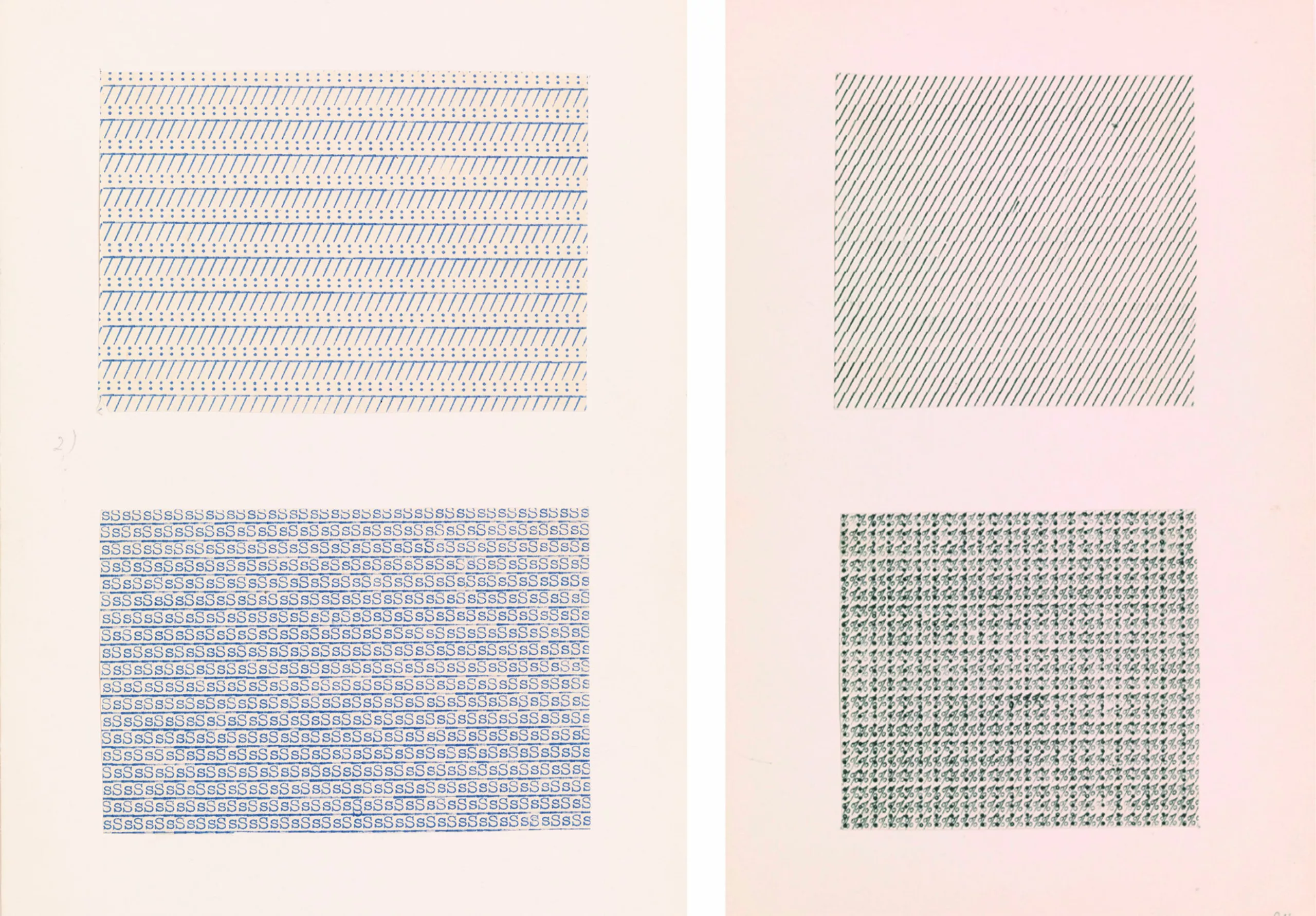

In the 60s, Anni Albers invented what she called “pictorial weavings”, “hybrid weavings between text and textile, page and canvas”, as the Guggenheim Bilbao explains, which she framed as works of art. Working her weavings from preparatory drawings (called “weaves”) that turn the motif into a coded language, she also explores the paper medium as a work through engraving, silkscreening, gouache, watercolor or drawing. When she gave up her loom at the end of the 60s, she turned definitively to paper, without stopping to “weave”.

Anni Albers plays graphically with prints, typefaces and motifs, inventing new weaves and weaves with typewriters and pencils to create type textures that can be reproduced on a larger scale. In this way, she forges a link between graphic design, art and industry. A parallel can be drawn between the weaves of the weaving loom and the graphic designer’s grid system, the template, or even the coded writing of pixels, which lay down a framework and rules for developing creativity. “Textile images are programmed images” writes Ida Soulard in her study of Anni Albers.

Alongside Gunta Stölzl, Sonia Delaunay and Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Anni Albers contributed to making weaving a noble, mass-reproducible art: a pillar of modern art, far from a purely decorative or utilitarian feminine activity.

Resources to explore :

- Fondation Josef et Anni Albers

- D’autres visuels du travail d’Anni Albers

- Les Albers et le Mexique, et leur inspiration commune pour l’art précolombien (Le Monde)

- Les parcours parallèles d’Anni et Josef Albers

- Anni Albers, toucher la vue (Guggenheim Bilbao)

- Livre : Du tissage, Anni Albers – Les Presses du Réel

- Sur l’art du tissage : La revanche de Pénélope (Le Monde)

- Ida Soulard – Anni Albers. L’horizon du silence