Toblerone’s new mountain: when packaging brands a territory

Made in Switzerland since 1908, Toblerone chocolate will have to swich the image of its emblematic mountain on its packaging, the Matterhorn. The reason for this necessary change? Relocation, because of globalization. This is our opportunity to look at what makes a territorial brand image, between labels and visuals.

Toblerone: made in Slovakia

Toblerone will now be produced in Slovakia, and the “Swissness” legislation prohibits the use of Suiss indicators from the chocolate country to promote it in a non-compliant way. Products labeled “made in Switzerland” must in fact contain at least 80% local ingredients made locally, and 100% for those containing milk (except for non-endemic materials, such as cocoa). The law indeed prohibits since 2017 to use the flag or other elements of the Swiss territory in food, industry or services. The Guardian newspaper points out that studies show that products with a Swiss label or image sell for 20% more, and up to 50% more for luxury products. By relocating its production, Toblerone no longer has the right to mention “of Switzerland” or to use the Matterhorn. The 4,478-meter-high Swiss mountain will be “replaced by a more generic peak” as the BBC explains, and the packaging will henceforth indicate ” established in Switzerland”.

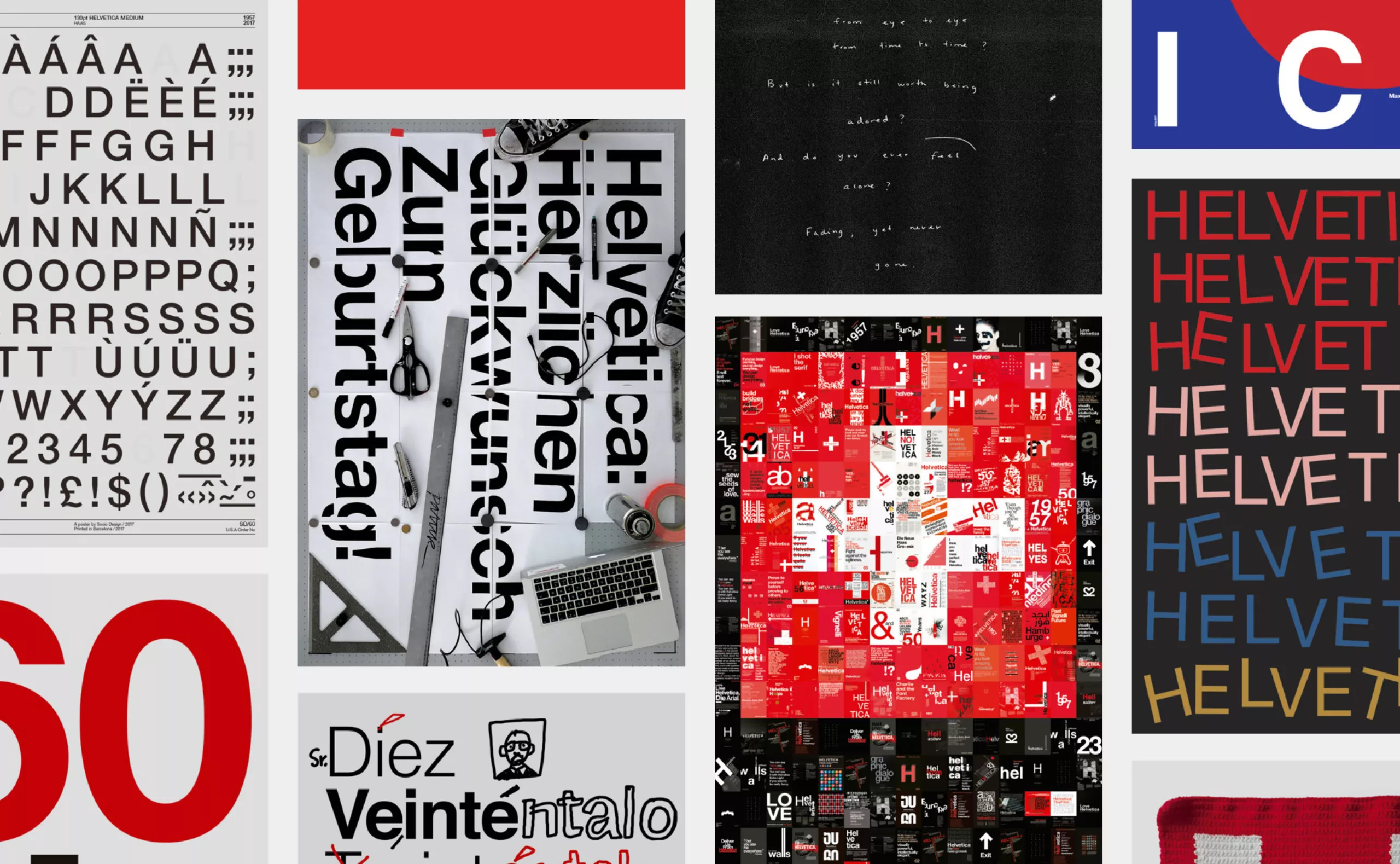

Toblerone already swiched identity (see images below) in 2022 with the agency Bulletproof, redesigning its letters to be more faithful to the original logo, and highlighting the chocolate triangle with a new, more vintage, handwritten typeface as a “genuine” writing, a signature, which bears the name of its founder; Tobler. Below we see the typographic work, with fuller letters with a gourmet and vintage look, and the product’s close-up. The new identity diverts the attention from an original and Swiss product to a gourmet and authentic product, even if it has nothing to do with Switzerland!

Until now the Toblerone Matterhorn also hid a bear, the heraldic symbol of the city of Bern, underlining twice its Swiss origin. One might think that this kind of bad publicity would be detrimental to the triangular brand, but when in 2016 Toblerone reduced the weight of its bars from 170g to 150g by spacing out the triangles, and then reduced their number from 15 to 11 a year later in Germany, sales soared…

Swiss chocolate, a fresh brand image in the prairie

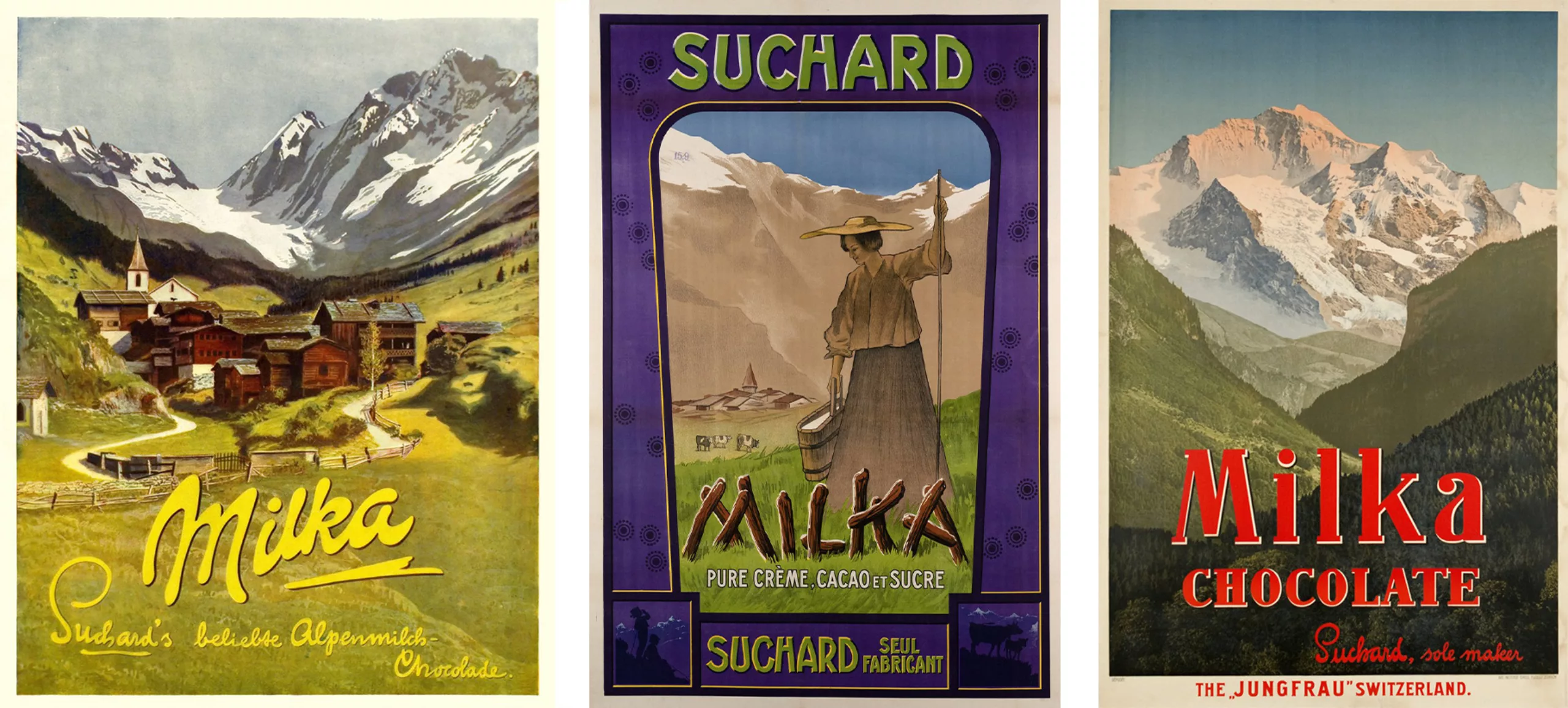

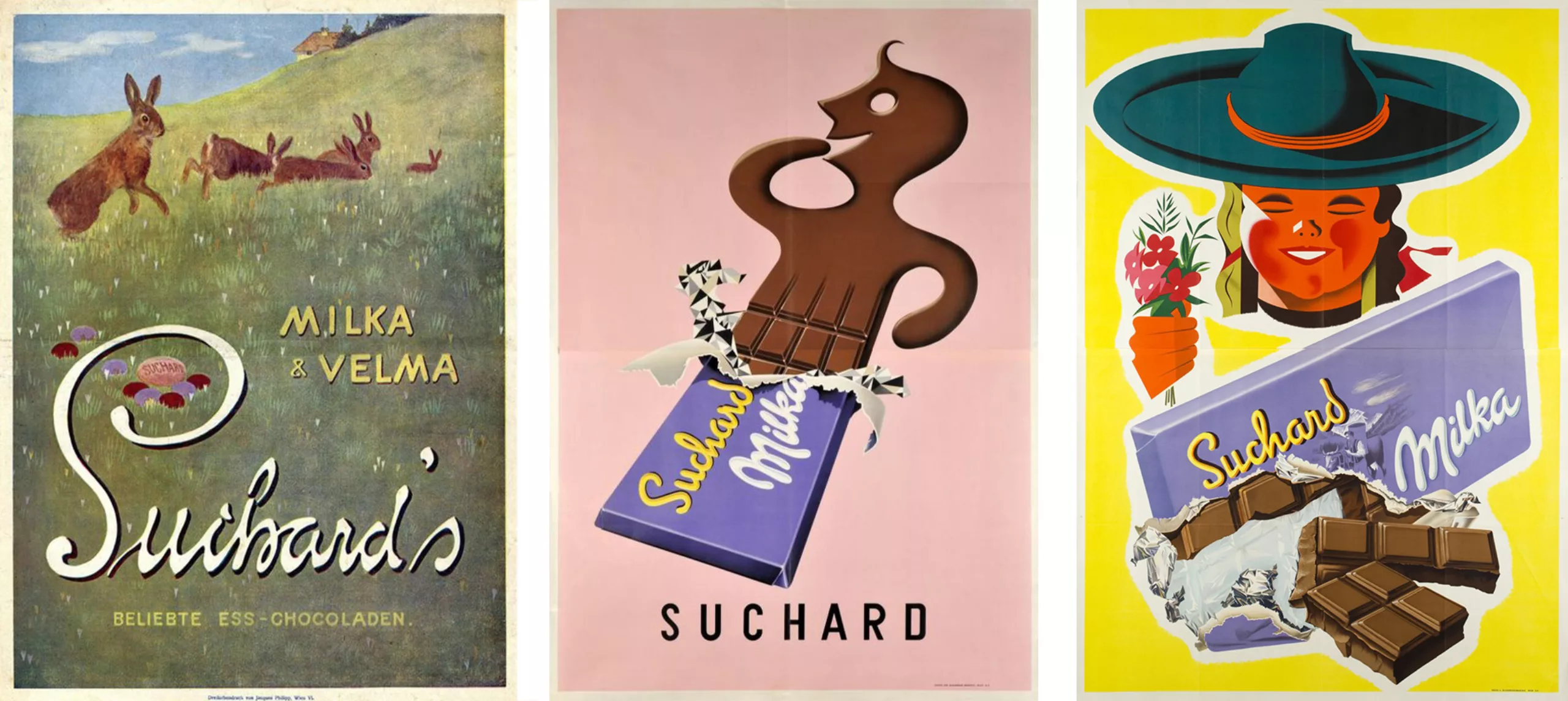

Swiss chocolate didn’t bloom alone from a green Suiss prairie. It took at least three people to build the empire and the quality image it still has today. Although the first chocolate bar appeared in England in 1847, it was François-Louis Cailler who invented the first mechanized chocolate factory in 1819 and set the chocolate stage amidst the snow-covered mountains, chalets and cows grazing in the Swiss Alps. At the end of the 19th century, Switzerland benefited from an important flow of foreign tourists who contributed to make their chocolate know-how and their delicious innovations known worldwide. These Suchard Milka posters from the beginning of the 20th century set the scene beautifully along with the shepherdess and her cows in the green valley, and the snowy peaks in the distance.

Suchard and Milka, the golden milk lilac cow

Originally, Philippe Suchard built the image of the typical “Swiss chocolate”, by opening a chocolate factory and then his first (dark) chocolate factory in an old mill in 1825, sold as a product with multiple virtues. With the arrival of the train, he exported to Germany in 1880. There he registered the brand Milka (Milch und Kakao = milk + cocoa) in 1901 (in Germany, actually). Prosperous, the Swiss protectionist measures encouraged him to set up local branches in foreign countries and he opened factories in the United States, England, Argentina, Sweden and South Africa after the 1st World War, well before the trend of globalization! Suchard then relied on milk, an abundant and inexpensive local product in his country, to make chocolate… with milk. The cow in the mountain pastures was present since the bar creation but it appeared in 1973 in the advertisements. Only in 1988 the whole image was built around the animal, the Alps and the famous lilac color. Like Toblerone, Milka now belongs to the giant Mondelēz (which owns oreo, tang, philadelphia… among others).

Peter and Lindt, golden bars

We owe the first milk chocolate bars to Daniel Peter, Swiss (obviously), who fell in chocolate as he fell in love, marrying the daughter of a French chocolate maker. In Lyon, he thus invented powdered milk chocolate, around 1875 (Van Houten had invented powdered chocolate in 1828 thanks to a degreasing press that removed the butter from the beans), before selling his golden egg (in powder) to Nestlé in 1929.

The third person to revolutionize Swiss chocolate was Rodolphe Lindt: he invented the first creamy-textured chocolate when he accidentally forgot to turn off a machine one weekend, which made it melt! He sold his patent 20 years later to Tobler, another Swiss, founder of Toblerone (we’ll come back to that). If the packaging did not yet feature the mountain back in the 1950s, the Matterhorn was clearly in the spotlight and the Swiss origin of Toblerone was undeniable (see pictures below).

Swiss chocolate, Greek feta and French Gruyère

Milka’s purple bars sold in Europe used to say “Swiss milk” and now less accurately state “100% milk from the Alpine country”: an area large and fuzzy enough not to be named, yet still retain its aura. As for Toblerone, the brand image is sufficiently anchored in the minds of consumers to be able to evolve without fear, or almost. The production plants are now located all over Europe and we are far from the family factory with marmots, cows and chubby children that we used to see in the ads!

A marketing trick that consists in continuing to purvey dreams by surfing on a solid brand image, and not revealing too much of its manufacturing secrets while delocalizing its production to reduce its costs. If Milka is purple, it’s probably because it still lacks transparency in a world that doesn’t want to be transparent to protect its interests. But it is far from being the only brand in the case! Dijon mustard is now made from Canadian mustard seeds and Ukrainian sunflower oil, and unless it is PDO, Gruyère can be French or American. French Gruyère -also PDO- has holes, unlike its Swiss cousin. As for Parmesan, Roquefort, Feta cheese, or mushrooms (grown in 70 countries), they no longer need to be produced in their country of origin: the recipe prevails over the location, even if the name is often protected. That’s the way globalization goes!

If we analyze the products below, real feta cheese can be recognized by the orange and red European PDO insignia, and the Greek milk (sometimes marked with a flag, sometimes not). The “100% ewe’s milk cheese” from Monoprix, is prepared with Greek ewe’s milk but does not have the right to the Feta label. It is nevertheless closer to it than Salakis or the “slices of ewe’s milk with French milk”, which are not feta cheese in the strict sense of the word, even though they use images on their packaging that make you think of Greece: the sea or a deep blue, a Greek-sounding name, or patterns. This is where we see the usefulness of labels on packaging and the importance of mentioning the territory of origin.

Made in France, but just a bit

For obvious reasons of brand image and to highlight a know-how, a territory or a particular product, brands can claim their origin. To use the label made in France, for example, a request is made to the customs authorities and requires that a certain number of ingredients come from France for foodstuffs, or that “the last substantial transformation” is carried out in France. Thus, one can produce fabric and cut a garment in Portugal but perform the last operations in France, such as sewing buttons, to obtain the label. When you know that 3 out of 4 French people are ready to pay more for a “made in France” product, the game is well worth it. France Industrie has created in 2021 an official label “made in France”, which comes in addition to the many other existing brands (bottom left in the image below).

There are indeed several labels to protect French foodstuffs. Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) for natural, agricultural and wine products or Geographical Indication for manufactured products and natural resources, Entreprise du Patrimoine Vivant (EPV) to distinguish artisanal and industrial know-how, Origine France Garantie which labels the place of production, Produit en Bretagne or Nou la fé in Reunion Island, both regional brands which guarantee the origin of local production based on precise specifications and criteria. France is the champion of protected or controlled appellations of origin (AOP / AOC) in Europe, which protect a specific origin or terroir and know-how, but which do not guarantee artisanal production.

Spotting fake Made in France scams

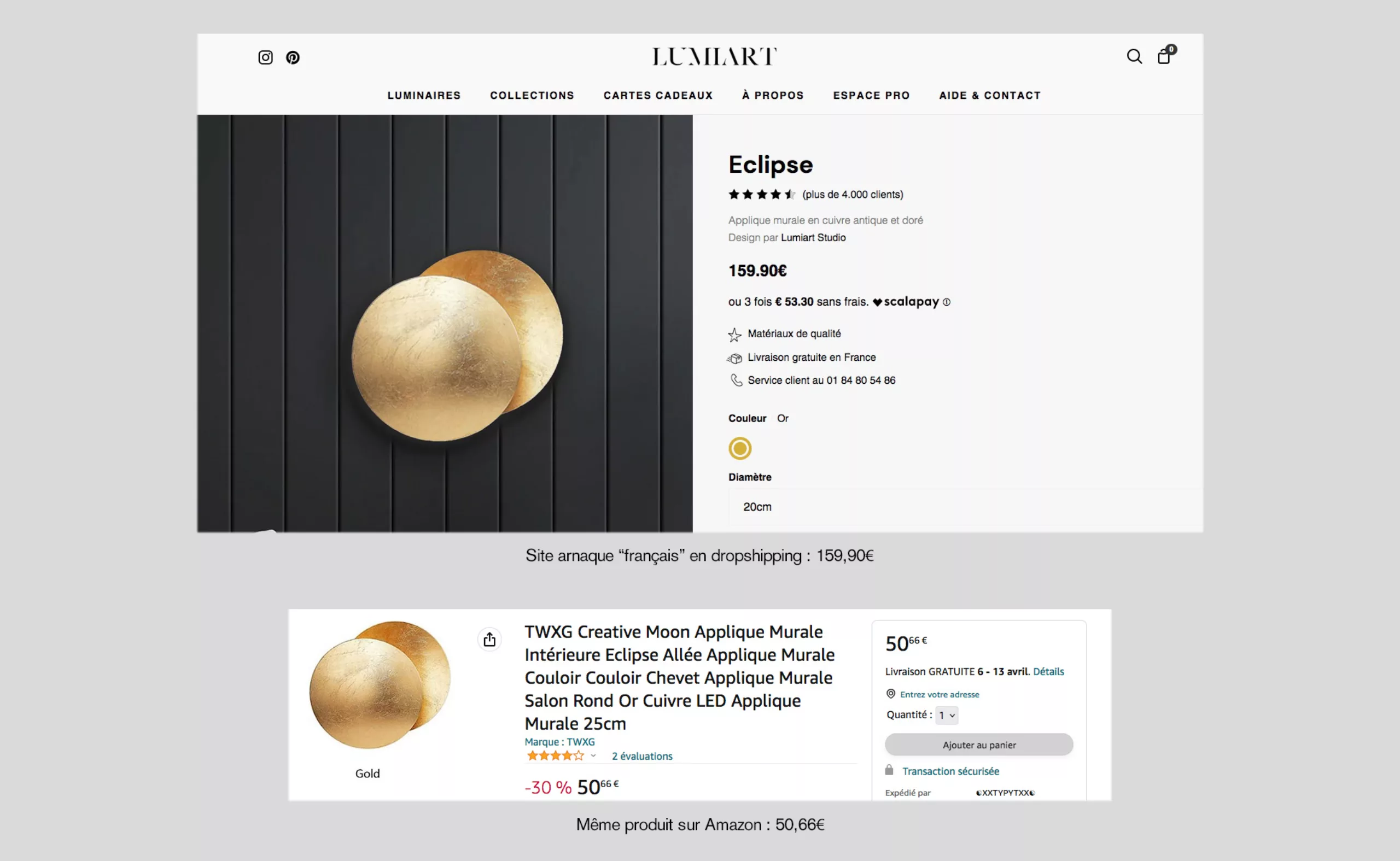

The new risk today is the advent of Chinese dropshipping sites: the customer buys from an intermediary site that orders from a supplier that ships to the customer. The scam here is to create “100% online” and trendy stores offering “design” and beautiful products in French style, presented in neat 3D decorations accompanied by fabulous customer reviews. Thanks to this “French” coating, they resell more expensive products, generally manufactured at low cost by Chinese companies. The name, logo, address and phone number point to a French location, or use French markers like the famous blue-white-red combo. But three colors are not enough to disguise a fake French product! So how do you spot fake Made in France scams made in China?

Here are a few hints: these brands always sell only online, the phone answers little and customer service is non-existent, the reviews are in bad French (usually translated) and the same products are available 3x cheaper on amazon or aliexpress, with exactly the same photos. The instagram accounts often have few followers or few publications. To get a real idea you can read real customer reviews on truspilot or type the name of the site + “scam” (example: lumiart scam) in your search bar to get a clear picture: this usually confirms the poor quality of the products, an overall dissatisfaction and the need to send back the non-compliant products to China.

It is also possible to point out a usurpation of the image of “made in France” on the site signal.conso (which does not seem to respond at the time of writing the article). In the case of the Lumiart site above, the address is “rue de la Pompe” under the mention “exclusively online store”, and the same lamps are sold 3x cheaper on Amazon… To be sure, the website marques-de-france lists the brands and products made in France: because it is not enough to have a crest and to say cocorico to be French!