A visit to Basel’s printing museum

The Swiss Museum of Paper, Writing and Printing (Schweizerisches Museum für Papier, Schrift und Druck in German) is dedicated to the history of papermaking, printing and writing in general.

The museum is housed in a building on the banks of the Rhine. As early as 1453, this building was used for paper production.

The museum’s historic rooms, with their graphic plates and collectors’ items, provide an insight into the ancient manual techniques of paper production, printing and bookbinding. Visitors can make their own paper in special tubs, print a sheet on a reproduction of a Gutenberg press, try their hand at calligraphy in a writing table, and make marbled paper in a priming bath. In short, this is a very entertaining museum with a very rich collection.

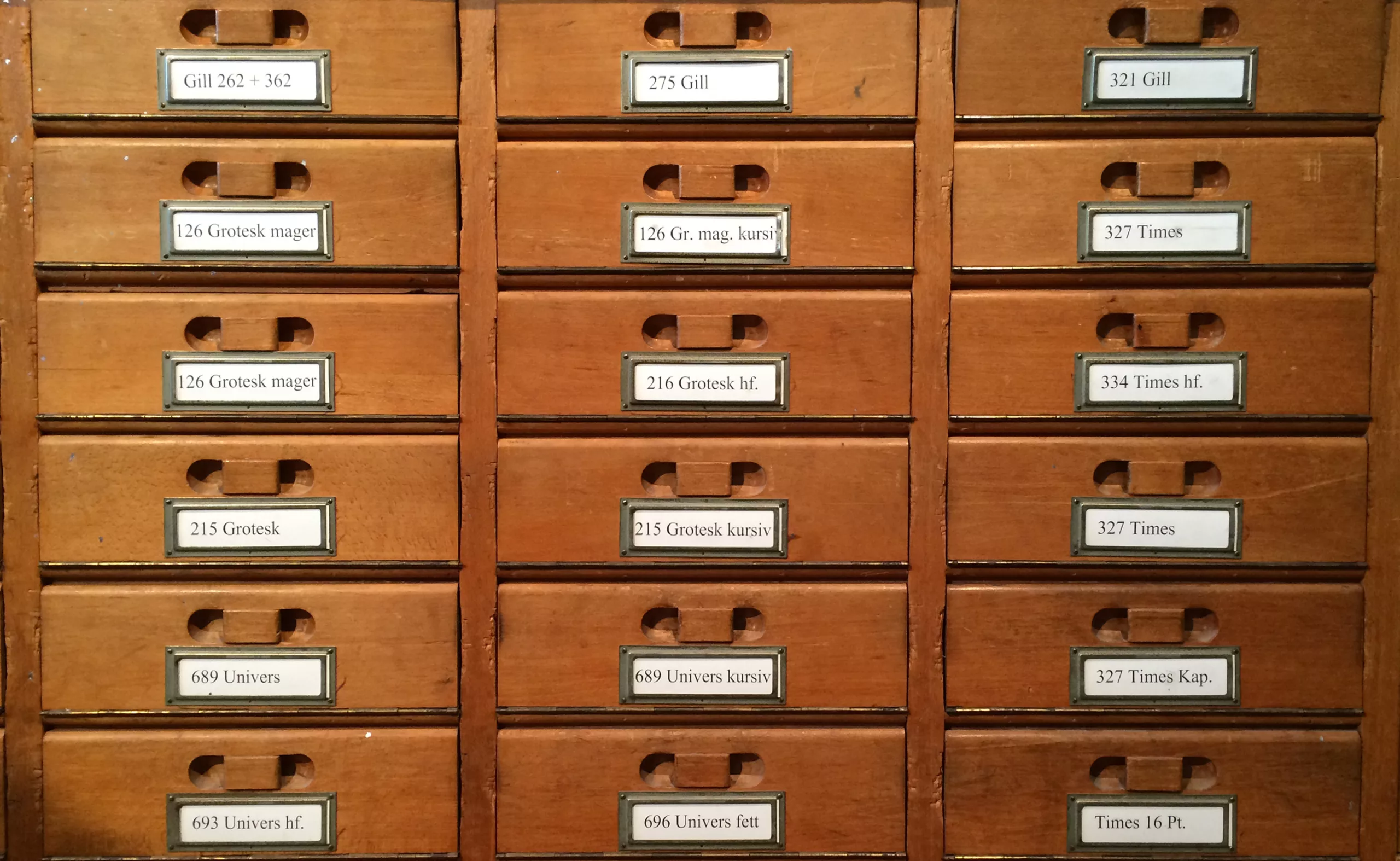

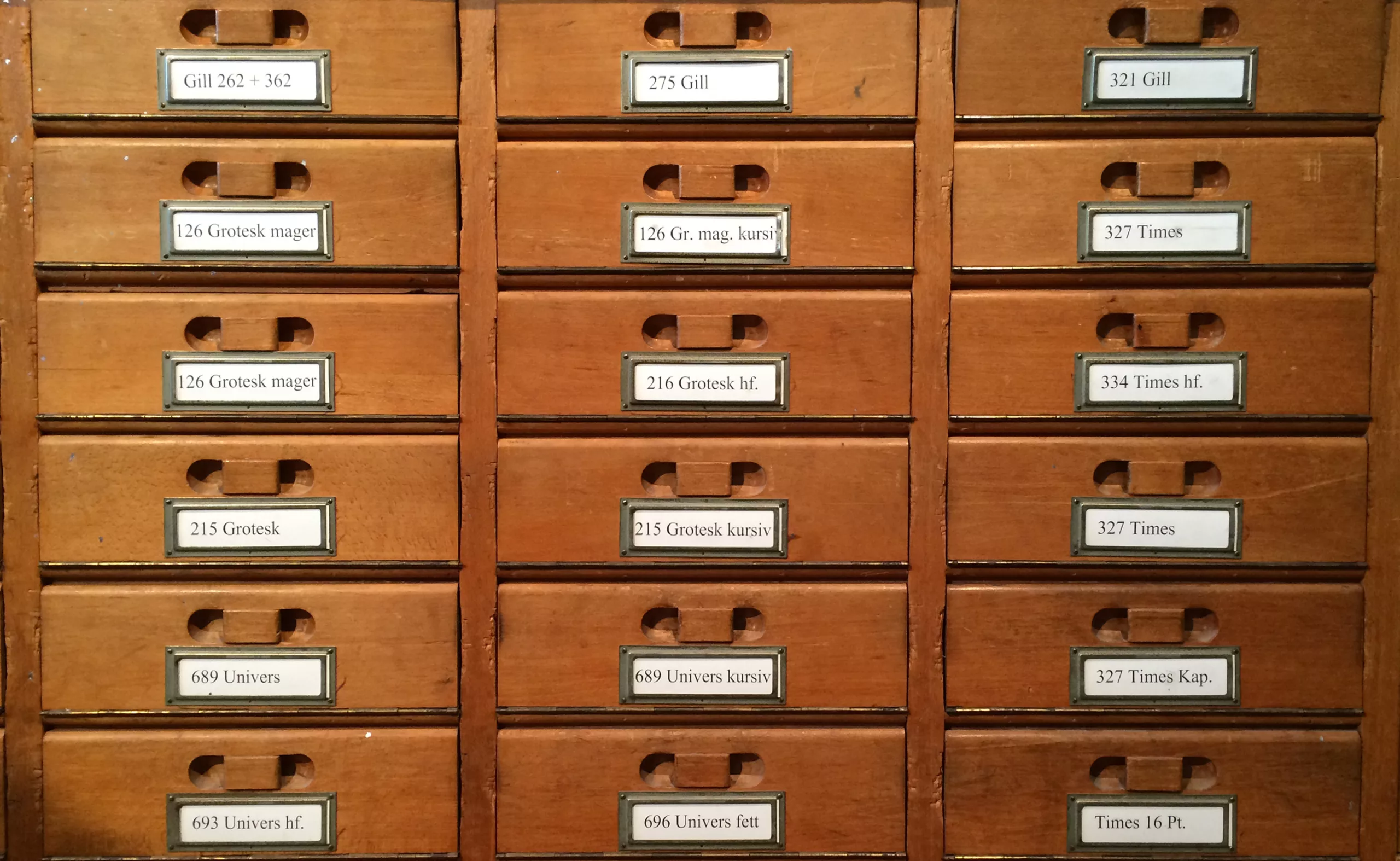

The funniest part is the “printer’s workshop”, a real little printing shop in working order. From the punch engraver’s workshop, a real type foundry, a typesetting workshop, and a printing workshop. It smells of ink, and you can even rummage around in the type breakers…

Here’s a video and photo preview of the visit.

The tour begins with paper manufacturer’s marks. These are thin metal wires twisted and welded onto the screen. The result is a “line” watermark. These wires make “clearings” in the sheet, which can be seen through the paper, as in the example below.

With the exception of a corner dedicated to typography games, the scenography is classic, giving pride of place to the original ambience of the place. The printing floor recreates a real printing workshop, smelling of ink and paper. During the tour, you can rummage through the drawers in search of lead typefaces for Helvetica, Times and the like.

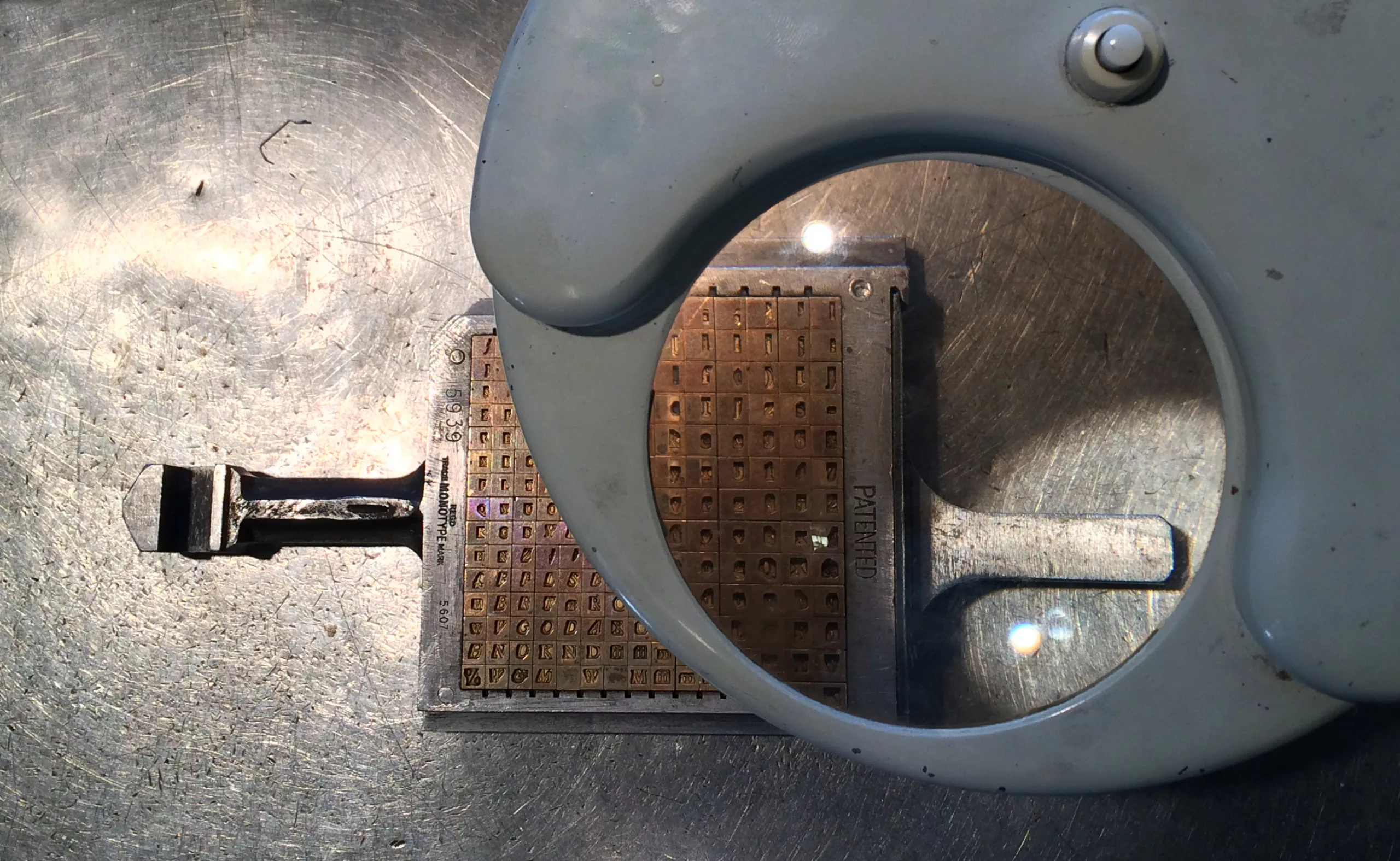

You can take a closer look at a few type dies. A matrix is the part of the mold used to melt the typeface. They therefore bear the hollow imprint of the typeface. Below, the same thing with lead typefaces once “melted” in the matrix !

Finally, on the last floor, you can make your own marbled paper. For me, it was like going back to childhood…

The Helvetica protocol

The unexpected treasure is the discovery of the Helvetica protocol.

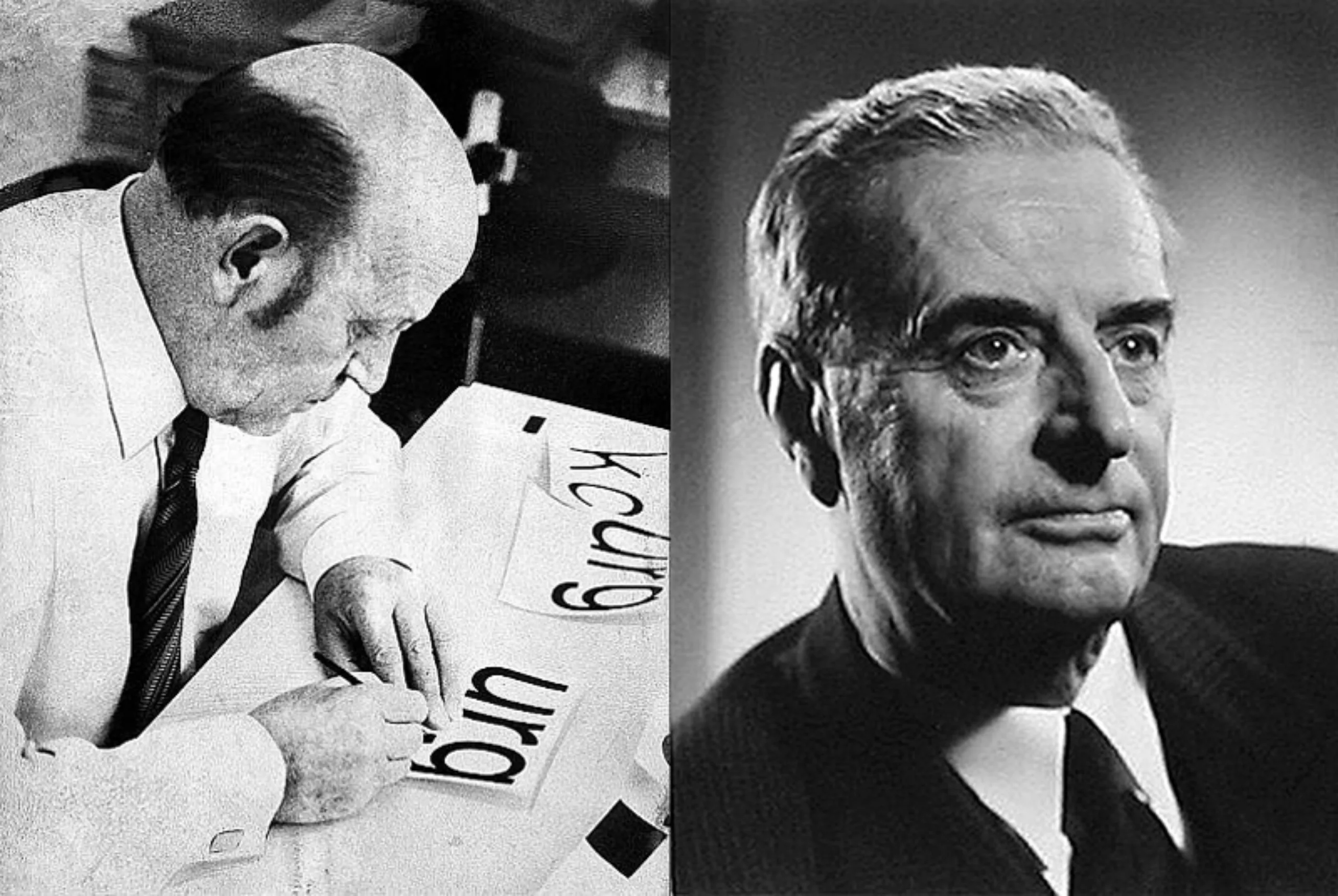

In case you haven’t lived on earth between 1960 and the present day, Helvetica is one of the most widely used typefaces in the world. In 1956, Eduard Hoffmann (1892-1980), director of the Haas Type Foundry in Münchenstein, commissioned Zurich graphic designer Max A. Miedinger (1910-1980) to create a new, grotesque sans-serif typeface.

By this time, the Haas foundry was seeing a decline in sales of its sans serif typefaces (“Grotesk” in German). Its typefaces were probably less modern than those of its competitors, such as the Berthold Foundry’s Akzidenz-Grotesk, widely used in Swiss graphic design (see: International Style).

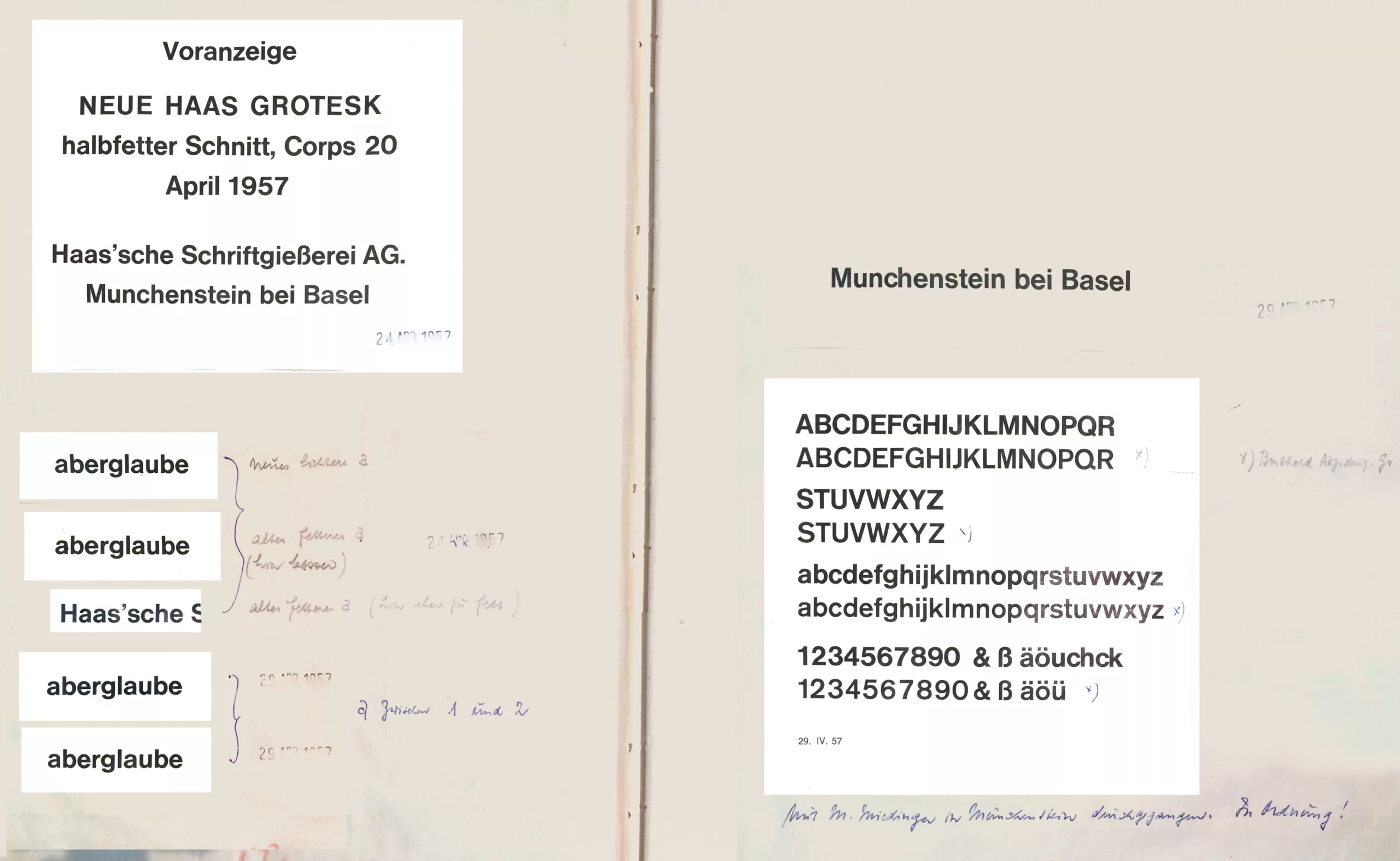

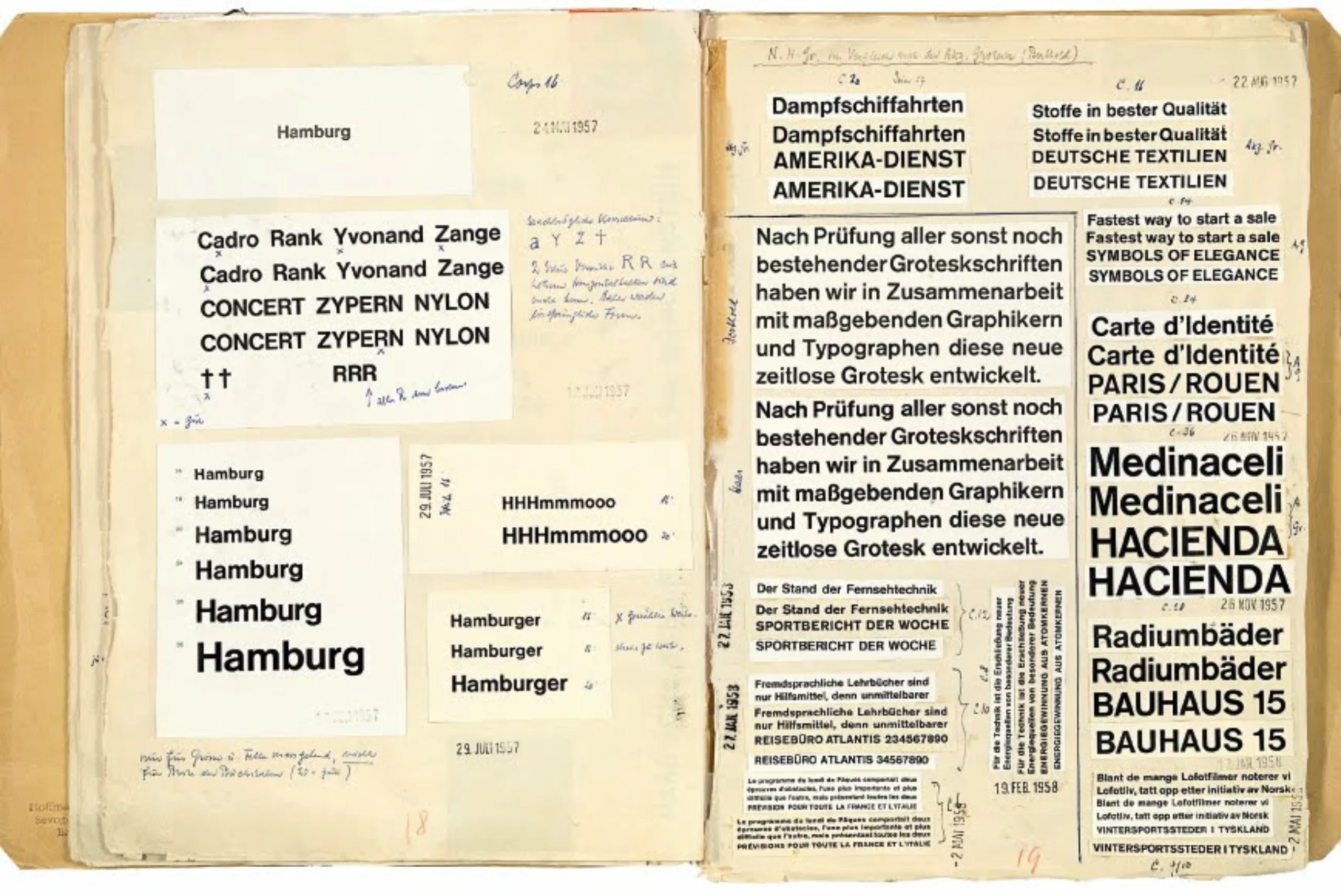

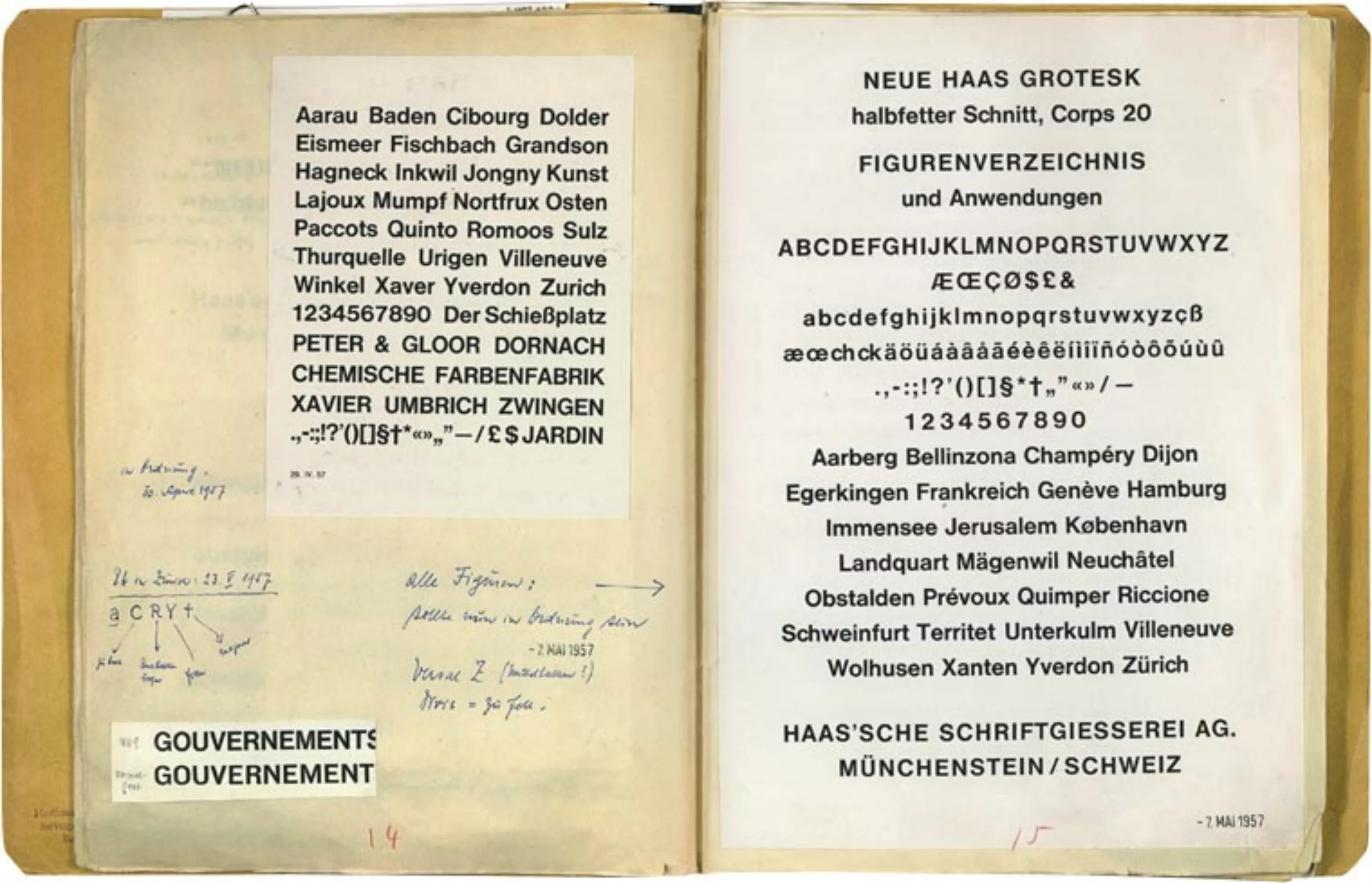

Work on the Neue Haas Grotesk began in the early autumn of 1956. Eduard Hoffmann-Feer, director of the Foundry, carefully recorded the various stages in the creation of Helvetica in a notebook. In it, he illustrates step by step, with proofs, the slightest changes made to each of the letters and the full range of possible typeface combinations. This unique document provides a detailed overview of the development of Helvetica.

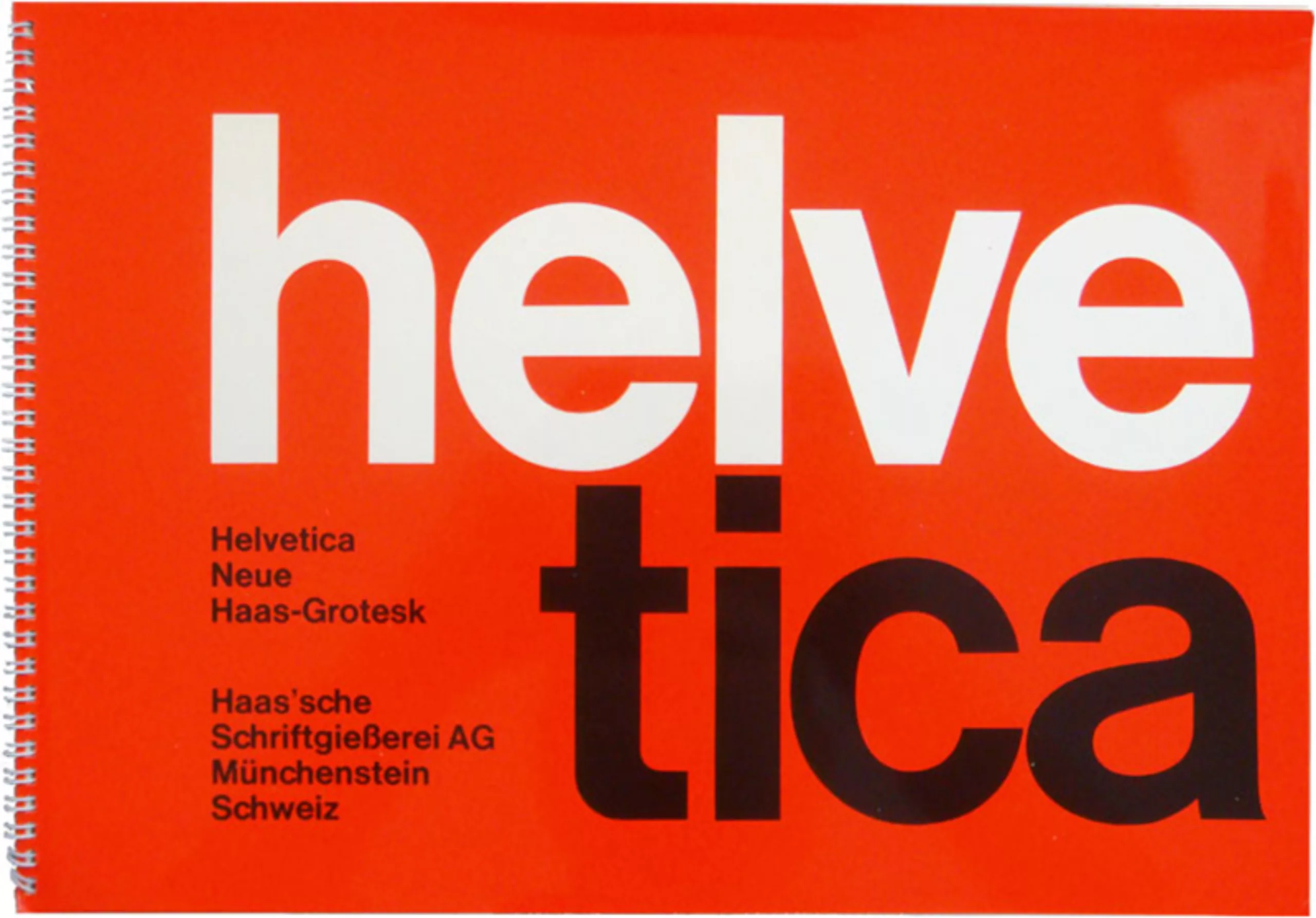

Under the name “Neue Hass-Grotesk”, the result was presented for the first time at the “Graphic 57” international trade fair in Lausanne, where it met with great success. The typeface was a perfect match for “Swiss typography”, which at the time had a strong international resonance. For marketing reasons, the name was changed to “Helvetica”.

Much of the credit for the success of this typeface went to Miedinger. Of course, he was the one holding the pencil! But Hoffmann’s contribution should not be underestimated. With his knowledge of the market and his customers, he was indispensable to this brilliant success.

The worldwide success of Helvetica remains unchanged to this day. It is by far the best-selling typeface on the market, and is available today in 110 different versions. Of course, it’s also found on thousands of logos around the world… here are a few of the best-known examples.

The end of the story

In 1971, Eduard Hoffmann set up a foundation with the aim of creating a museum dedicated to the printing industry. In 1980, the museum opened in a former paper mill on the Rhine. The Helvetica protocol is one of the museum’s main attractions. Eduard Hoffmann died in Basel on September 17, 1980.

Between 1972 and 1978, Haas bought the best-known French foundries, Deberny & Peignot, then Fonderie Olive (from Roger Excoffon). At the time, the Haas foundry was majority-controlled by the Berthold AG foundry, and when the latter was taken over by Lynotype in 1985, Haas passed into German hands. The Haas foundry closed in 1989.

A short history of the name “Linotype”

German inventor Ottmar Mergenthaler developed a composing machine equipped with a magazine of brass dies, which could be used to melt lines in one piece. The first machine was built in 1886 and presented to the editor of the New York Tribune, who enthusiastically exclaimed “Oh, a line of types! Hence the name Linotype.

The Linotype composing and fusing machine was mainly used in newspaper publishing. It increased a typographer’s hourly productivity sixfold. To compose, the operator presses a key on the keyboard and drops a die from the magazine into a channel, then dispatches it into the compositor. The composed line is then automatically sent and formed in the melting device. During the melting process, the operator can already dial the next line. Thanks to a sophisticated system, dies are automatically redistributed in the magazine after melting.